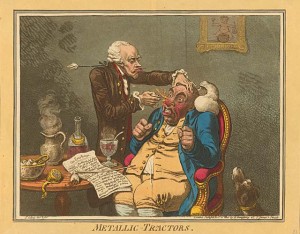

An accomplished young lady – Mary Crawford plays her harp

The accomplishments of women comes up rather frequently in Jane Austen’s novels. These are nicely summarized at The Jane Austen Information Page at the Republic of Pemberley. The question is, however, when Jane Austen allows Darcy to mention that, to all of the Bingley tribe’s common place “accomplishments” something else was to be added- substantial reading,- was she representing her attitude or that of society in general?

Let’s take a quick look (also gleaned from The Republic of Pemberley).

During the early part of the 18th century girls education was very rooted in domesticity. In 1704, a letter from John Evelyn states that girls should be brought up to be:

humble modest, moderate, good housewives, discreetly frugal,without high expectations which will otherwise render them discontented..

This was typical of the general attitude. Gradually the list of topics a girl was expected to master was extended by a set of “accomplishments”- more in line with the Bingleys’ thinking: sewing, embroidery, management of their hosuehold, writing elegant letters with an elegant hand, walking and dancing elegantly, singing, drawing, playing the harpsichord, reading and writing French.

The Bingley sisters were educated at an expensive seminary where great import appears to have been placed on such, when viewed in isolation, trivial accomplishments.

However as they became almost universal accomplishments – due to the growing middle class begin able to afford to send their children to schools where such topics were taught-these limited options lost some of their social cachet.

Maria Edgeworth

Towards the end of the 18th century there was a move towards an education based on moral education and intellectual stimulation. In her book, Practical Education, Maria Edgeworth’s ideas were influenced by Rousseau’s theories of child rearing where it was assumed that children were rational human beings and that they should be taught by example and be reasoned with rather than punished.

The syllabuses recommended by Practical Education included such topics as chemistry, mineralogy, botany, gardening – a very suitable occupation as it combined academic study with exercise outdoors. Children were encouraged to play with “toys that afforded trials of dexterity and activity such as tops kites, hoops, balls, battledores and shuttlecocks ,ninepins and cup and ball.”

Maria Edgeworth was also keen on children avoiding bad company- particularly that of servants, who could influence them by their vulgar manners: “If children pass one hour in a day with servants it will be vain to attempt their education.”

Hannah Moore

This is the stance that was taken by Hannah Moore too. Her book, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, was published in 1779. She believed that girls should be given a rigorous academic education, but that the emphasis was still to be on maintaining propriety. The aim of her educational book was to produce well- mannered, lively, and intelligent companions for husbands and children.

Here is Hannah Moore’s view of female education:

A lady may speak a little French or Italian, repeat passages in a theatrical tone, play and sing, have her dressing room hung with her own drawings, her person covered with her own tambour work, and may notwithstanding, have been very badly educated.Though well-bred women should learn these, yet at the end a good education is not that they may become dancers, singers, players, or painters but to make them good daughters, good wives, good Christians.

The importance of moral education was also advocated by John Locke in his influential work (published initially in 1693 ,but by 1777 there had been 25 editions) Some thoughts Concerning Education.

He advocated a private education within the home- not attendance at school, where children’s morals might be corrupted by association with children and masters of a lesser moral caliber. This became a common factor in education of girls during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

How about the young ladies in your books? What kind of education have they had? Are they satisfied with it?