[tw: rape, racism, violence]

Note: This got long, so I’ve moved all links for further reading/listening/viewing that couldn’t simply be hyperlinked in the main text to the end of the post.

Note 2: Jefferson’s party are Republicans, Hamilton and Adams’s are Federalists.

As a result I’ve been reading extensively about Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the political scene of their era. And I noticed one name kept cropping up: James Callender. This British journalist seemed surprisingly connected to events: he leaked the first documents relating to Hamilton’s alleged insider trading (leading to the infamous “Reynolds pamphlet” in which Hamilton revealed in excruciating and excruciatingly unnecessary detail that…well, I’ll let him tell it:

“The charge against me is a connection with one James Reynolds for purposes of improper pecuniary speculation. My real crime is an amorous connection with his wife, for a considerable time with his privity and connivance, if not originally brought on by a combination between the husband and wife with the design to extort money from me”).

Title page of the Reynolds pamphlet, via Wikimedia Commons

Callender next appeared ruining John Adams’s bid for reelection. Callender had published, among other things, a pamphlet entitled The Prospect Before Us, in which he made statements like, “The grand object of [Adams’s] administration has been to exasperate the rage of contending parties, to calumniate and destroy every man who differs from his opinions. Mr. Adams has laboured, and with melancholy success, to break up the bonds of social affection, and, under the ruins of confidence and friendship, to extinguish the only beam of happiness that glimmers through the dark and despicable farce of life.”

Adams had him prosecuted for libel under the (deservedly) unpopular Sedition Act. Jefferson’s supporters turned the trial into a major campaign issue in the 1800 presidential election, and Callender’s conviction, instead of discrediting him, made him a famous martyr to the Republican cause. Moreover, he continued to write articles and pamphlets lambasting Adams from his Virginia jail, where the authorities were sympathetic to his plight.

Then I read this, in A Magnificent Catastrophe by Edward J. Larson:

“Ironically, Jefferson later felt Callender’s sting, when, two years after the election, the acerbic writer broke the story that Jefferson kept his slave, Sally Hemings, as a mistress. ‘Human nature in a hideous form,’ Jefferson wrote to Monroe in 1802 about Callender, whose body was found floating in Virginia’s James River a year later. An inquest ruled that Callender had drowned accidentally while bathing drunk.”

Jefferson totally had that guy killed, I thought to myself. Wouldn’t that make a great political thriller? You could open it with them fishing that guy’s body out of the river, and then cut to “Five years earlier”…

At first it was a joke. But the more I read and research, the more convinced I feel that this was exactly what happened. While all the evidence is circumstantial…well, I’ll let the facts speak for themselves:

1. Turns out, Callender spent a significant part of his US career as Jefferson’s personal hatchet man!

The Reynolds-Hamilton documents he printed were last seen in the possession of John Beckley (“one of Jefferson’s most devoted followers” according to Thomas Fleming’s Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America) who had been given them by James Monroe, a Jefferson friend, trusted ally, and occasional Cabinet member, who himself served as a go-between for Jefferson and Callender on other occasions.

(When Monroe denied leaking the documents, Hamilton called him a liar and the two men almost fought a duel.)

Jefferson’s personal notebooks confirm that he “helped Callender financially in three ways. He helped him find work, he bought his pamphlets, and he gave money outright to him. The first payment to Callender made by Jefferson was for $15.14 for multiple copies of Callender’s series of pamphlets History of the United States for 1796.” [source]

In fact, Jefferson had read advance proofs of The Prospect Before Us (which included attacks on the nation’s beloved George Washington as well as Adams) “and returned them with a warm letter, declaring: ‘Such papers cannot fail to produce the best effect.'” (Fleming.) He also donated $100 toward its publication costs.

After Callender broke with Jefferson (apparently because Jefferson refused to extend his patronage to giving the journalist a government job), he reprinted the aforementioned warm letter, and shared various other information about his association with the president.

Jefferson’s public response was essentially, “I just felt sorry for him, he was a charity case and nothing more.” Super convincing, dude.

2. Callender’s article on Sally Hemings (published Sept. 1802), while not the first on the subject, made her and her children with Jefferson a widely believed national story.

Many Hemings deniers (the scum of the earth IMO) have argued that Callender’s article is full of small factual errors and that this means Callender was talking out of his ass and the whole story is a lie. To me, the most interesting statement in the article is this: “By this wench Sally, our president has had several children. There is not an individual in the neighbourhood of Charlottesville who does not believe the story; and not a few who know it.”

Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings was an open secret in his hometown, in other words, despite being a vague rumor in the rest of the country. Callender was not printing the results of a careful journalist exploration; he was simply breaking the code of silence by which Virginian Republicans hushed up things (even ones widely known among themselves) that could discredit their party’s head.

The article closes with this dig: “When Mr. Jefferson has read this article, he will find leisure to estimate how much has been lost or gained by so many unprovoked attacks upon, J. T. CALLENDER.”

Or it could also be a threat. Did Callender, after years as a Republican insider, know more he hadn’t told yet?

3. While Adams was prosecuting Republican printers like Callender for libel, Jefferson opposed the Sedition Act as an assault on the freedom of the press (which it was). As soon as he became president, he had a change of heart and quietly let it be known among his followers that it was open season on his own enemies in the press.

The Republican political machine in New York chose as their scapegoat Federalist printer Harry Croswell, who had reprinted Callender’s story that Jefferson paid him to talk shit about Washington and Adams.

Harry Croswell in 1835, after he left the press to be a clergyman. image via Wikimedia Commons.

New York’s attorney general (a Republican who Croswell had also attacked in print) and a Republican political appointee Supreme Court justice managed the trial between them. The judge “told the jury that the libel law of New York followed the common law of England, which made any criticism of the head of state a crime, whether or not it was true.”

This at the behest of the author of the Declaration of Independence!

Alexander Hamilton agreed to argue Croswell’s appeal. Not only did he tell everyone he was planning to subpoena President Jefferson himself (oh, that must have been fun for him!), but as his case would hinge on the truth of Croswell’s assertions, he must have hoped to subpoena Callender as well—and Jefferson must have known it. The timeline here is not entirely clear to me yet but however you figure it the timing is suggestive:

Dec. 20, 1802 – Someone with links to Jefferson violently assaults Callender and shortly thereafter has him jailed on specious charges [see point 3, below]

Jan. 11, 1803 – Croswell arrested. His attorney requests the trial be delayed until Callender can be subpoenaed from Virginia. The request is denied.

July 11, 1803 – first Croswell trial (probably lasting only a day, but maybe two; I haven’t found confirmation on this point)

Night of July 17–18, 1803 – Callender dies. He is found at 3AM on the 18th, an inquest is held at once, and his body is buried the same day (rather unusual for the time, when bodies tended to kind of sit around after death).

I haven’t found when Hamilton’s intentions to appeal the case were announced, but it could have been at once, or the possibility could even have been mentioned before the first trial. He was already helping with the case in late June.

4. Callender had already been violently physically assaulted by a loyal Jeffersonian: in December 1802, “George Hay, a member of the Virginia governor’s executive council and James Monroe’s son-in-law, [italics mine; Hay, BTW, had been Callender’s defense attorney back when Callender was still in Jefferson’s pay and Adams was prosecuting him] had viciously battered the newspaperman on the head with a club…and then persuaded a Virginia court to silence Callender on the extremely dubious argument that English common law entitled the state to require a ‘common libeller of all the best and greatest men in our country’ to post a bond against committing further offenses. Rather than put up the money, Callender went to jail.” (Fleming.)

Callender stated in court that only wearing a high-crowned hat saved his life.

Not only that, but in March 1803, young Republicans who mostly worked for Hay’s law firm stormed Callender’s printing office and threatened to burn it down—and might have, if not driven off by muskets. This was most likely just hooliganism (although it could have been an attempt to destroy Callender’s papers, some of which were relevant to the Croswell case; the young men had come straight from a Republican party event). But it certainly shows that neither Jefferson or Monroe were averse to violence against Callender, since they had plenty of time after Hay’s first assault to tell him and his friends to back the fuck off.

(To explain a six-week absence from work shortly after this, Callender said he had met with another unspecified accident in which he lost a lot of blood. But his business partner, with whom he was publicly quarreling over money, claimed he was just on a bender. You decide!)

5. Callender drowned in three feet of water. (One Jefferson supporter said he drowned in “congenial mud.” A charming bunch.)

Yes, Callender had a history of alcoholism and had been seen drunk the evening before (his body was found at 3AM). Certainly drunk people do accidentally drown. But also, how easy is it to quietly drown a very drunk man, or else kill him and throw his body into the water?

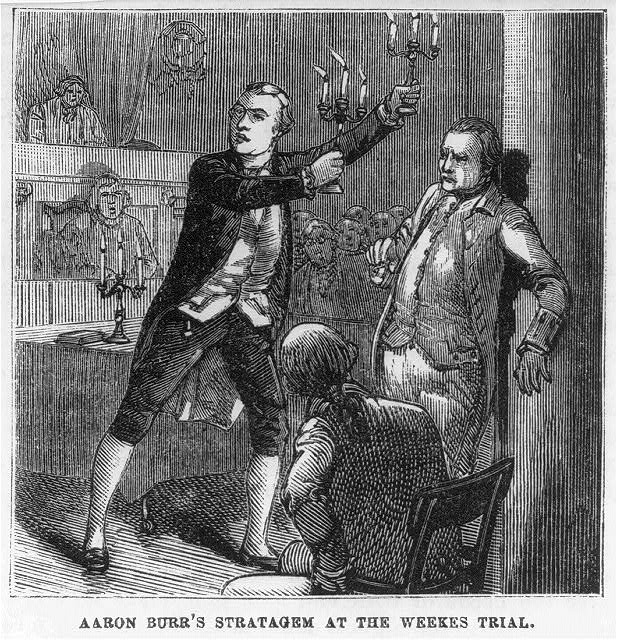

Could contemporary forensic science have accurately determined cause of death? Probably not. In the 1800 Elma Sands murder trial in New York, the autopsy doctors did look for water “in the body” but on the stand they were unwilling to hazard a firm opinion as to whether the victim had drowned, or whether she had already been dead when she went into the water.

Hamilton and Aaron Burr worked together as defense attorneys on the Sands trial. They both later claimed to have made the dramatic gesture pictured here. The trial transcript, I believe, sides with Hamilton, although it was probably Burr’s idea. Image via Library of Congress.

Nor were coroner’s juries obligated to agree with the doctors’ findings in their verdicts. The autopsy doctors in the Sands case (already a cause célèbre at the time of the inquest) found no marks of violence on the body and thought suicide a stronger possibility than murder (they were later proven wrong by events, another strike against contemporary forensics), but the jury ignored them and returned an unqualified verdict of murder to avoid rioting or reprisals.

I’ve emailed the Library of Virginia, which holds coroners’ records from the period, but haven’t heard back yet. In the meantime, we’ll take Larson’s statement as fact: “An inquest ruled that Callender had drowned accidentally while bathing drunk.”

(Sidenote: how could they possibly know if he was swimming or had fallen in? Was he undressed? I haven’t seen it suggested anywhere that he was!)

Now for the big question: who were the coroner and jury at that inquest? Almost certainly, political supporters of Jefferson.

Coroners in 1803 were part of the political machine that used civil service jobs as patronage, i.e. rewards for past political loyalty. (See above about Callender being furious and insulted at not getting one.) Government jobs, and the fees and salaries that came with them, were the glue that held ruling political parties together. Jefferson and his friends were the party that ruled Virginia.

I have been trying to figure out exactly how coroners were appointed in Virginia in 1803 (as well as the identity of the coroner in this case) and failing. The best I can come up with is this statute from 1819, which purports to follow a previous act of 1792 in substance:

Source: Google books

So the court sends the governor two names and he picks one to be coroner? Many local judges were of course also part of the political machine!

The governor of Virginia from 1802 to 1805 was John Page, Jefferson’s best friend from college. And the previous governor of Virginia was none other than…James Monroe himself. Monroe held the office from 1799 to 1802, and there are many mentions in his papers during that time of coroners’ appointments (I notice that most of them only record one name as being recommended, not two).

The counterargument here is that “during good behavior” was understood to mean “for life unless impeached.” (At least, that’s what it meant AFAICT from Fleming’s discussion of Jefferson’s attempts to destroy the independent judiciary.) And there WERE a couple of Federalist governors of Virginia in the preceding decade.

How about the jury?

Sounds to me like motive, means and opportunity not only to commit the crime, but also to cover it up.

Hamilton: the Musical

· Watch a few clips of numbers from the show

· See creator Lin-Manuel Miranda perform the introductory song at the White House Poetry Jam

· Stream free on Amazon Prime or Spotify.

The Reynolds Pamphlet

· The published pamphlet and Hamilton’s original draft. (I am definitely not trying to justify his multiple dick moves here, but there is something touching and pathetic to me about the way, when writing of the pain he knows he is causing his wife, he wrote “And I can only throw myself upon [her] gener” and then crossed it out.)

Sally Hemings

· The text of the original Callender article. Be warned, it is racist.

Researching Sally Hemings—who Jefferson started raping when she was between 14 and 16 years old—is enraging and painful, both for the subject matter and for what people have to say about it. Do yourself a favor and NEVER READ THE COMMENTS. These three articles at least don’t try to claim she was lying about TJ being her children’s father: monticello.org, Wikipedia, and Encyclopedia Virginia. The last one has a lot of detail about Hemings’s life but makes some upsetting statements about master/slave sexual relations.

The Croswell case

· A detailed law review article about the case

· Wikipedia

I conclude with this sad and inaccurate entry in the European Magazine and London Review of 1803:

ETA: I have just heard back from the Library of Virginia: “For 1803 there is no separate group of Richmond City coroner’s records. The coroners records may be interfiled with the Richmond City Ended Causes. There are three boxes for 1803 (Barcodes 1130413, 1130414, and 1130415) These records are served in our manuscript room, which is open Monday-Saturday, 9-4:30.”

If any of you live in Richmond and would be willing to go there to look for the record, I would be more than happy to offer some kind of small reward, like a book or a $10 Amazon gift card or an advance copy of Listen to the Moon—in addition, obviously, to my eternal gratitude. The website recommends making an appointment in advance.

Yep, it’s pretty stinky. I don’t know why people would think TJ was above a quietly arranged murder. He repeatedly showed, as well as other “Founding Fathers” that he knew full well about history and he cared deeply about what was printed about him. The Declaration of Independence itself is proof of this if nothing else. Thank you for writing this great post.

Thanks! I agree completely, this would be in character for him. I have come across SO MANY examples of him doing unsavory things through a few layers of friends and private meetings, and then publicly disavowing them.

[…] Read all about it. […]

I can’t say that I agree with your conclusions or not, either way, but then I’m a cautious sort. It’s certainly an interesting string of details…

One thing I can say is I don’t like how the Founding Fathers have somehow become deified in American culture, rather than being seen as complex and flawed human beings.

very interesting stuff, Rose!

[…] In which Rose Lerner goes all conspiracy theory about the death of a journalist. This is really intriguing stuff. Did Jefferson have that journalist killed? Maybe! Maybe not! […]