How much do you know about LGBT history during the Regency period? Today we offer you a guest post by writer Graham Stokes (who happens to be Risky Gail Eastwood’s son).

As most of you probably know, June is LGBT Pride Month. The month is generally filled with gregarious celebrations commemorating the Stonewall Riots which occurred on June 28, 1969 and launched the modern LGBT rights movement as it is known today. But the history of the LGBT community goes back much farther than that. Here’s a glimpse of it specifically during the Regency period.

As most of you probably know, June is LGBT Pride Month. The month is generally filled with gregarious celebrations commemorating the Stonewall Riots which occurred on June 28, 1969 and launched the modern LGBT rights movement as it is known today. But the history of the LGBT community goes back much farther than that. Here’s a glimpse of it specifically during the Regency period.

To start, let’s talk terms. Of the words that make up the acronym LGBT, only the word “lesbian” was used in the Regency with the same meaning as it has today. Even though we’ve used “queer” in our post title, it actually just meant weird or deviant back then, without any specifically sexual connotation. Homosexuals were known as “mollies”. Some sources say this was an evolution of 18th century slang when a “Molly” meant an effeminate man.

In the British Empire, not only was homosexual behavior between men still illegal in the Regency era, it still carried the possibility of a death sentence. Homosexual and transgender people were forced into hiding. Taverns, coffee houses, and other businesses that could provide cover for them were called “molly houses”.

Molly houses were primarily establishments where men could meet other men –or male prostitutes, a practice that was increasingly common by the Regency period –for sexual encounters. However, these houses were also the hub of what little community there was for LGBT people.  Cross-dressing was commonplace inside molly houses. Some outdoor locations, such as public toilets and certain public parks and thoroughfares, became known as “molly markets” but served much the same purpose as molly houses.

Cross-dressing was commonplace inside molly houses. Some outdoor locations, such as public toilets and certain public parks and thoroughfares, became known as “molly markets” but served much the same purpose as molly houses.

For convenience (of the authorities), pillories were often built near these places, because of how frequently offenders were placed in them. Ironically, this meant that pillories often became an identifier of a place where a molly market might be, rather than a deterrent from seeking one.

Early in 1810, James Cook and someone named Yardley (full name unknown) opened a molly house on Vere Street called the White Swan. Both men would later claim they had wives and kids, were completely straight, and were only operating the molly house for the money. On July 8, less than six months after the White Swan opened, Bow Street Runners raided the place.

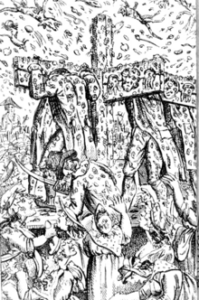

Th is Vere Street coterie, as it was called, was reported in every newspaper. Twenty-seven men were arrested, though only eight were prosecuted and convicted for the crime of buggery. Six of them, convicted only of “attempted sodomy” (a subset of the umbrella term “buggery”), were pilloried in the Haymarket on September 27. A large and unruly crowd came out to watch the punishment and hurl things –reportedly including dead cats –at the “mollies”. The city was forced to deploy 200 armed constables to prevent anything worse from happening.

is Vere Street coterie, as it was called, was reported in every newspaper. Twenty-seven men were arrested, though only eight were prosecuted and convicted for the crime of buggery. Six of them, convicted only of “attempted sodomy” (a subset of the umbrella term “buggery”), were pilloried in the Haymarket on September 27. A large and unruly crowd came out to watch the punishment and hurl things –reportedly including dead cats –at the “mollies”. The city was forced to deploy 200 armed constables to prevent anything worse from happening.

The following spring, on March 7, 1811, 46-year old John Hepburn and 16-year old drummer boy Thomas White –both convicted of engaging in the actual act of sodomy –were hung despite neither of them being present at the White Swan at the actual time of the raid. The lawyer Robert Holloway would write a book about the incident, published in 1813, entitled The Phoenix of Sodom.

This would not be the end of the scandal stirred up by the Vere Street coterie. The Weekly Dispatch reported that the Reverend John Church had been performing false marriages between the male clients of the White Swan. The rumors are, at this point, unprovable but the modern LGBT community of the UK claims John Church performed the first same-sex marriages in England. For his part, Reverend Church denied the accusations, claiming they had been started by his rivals in the clergy. He took legal action against the Weekly Dispatch to ensure such stories were not reported again.

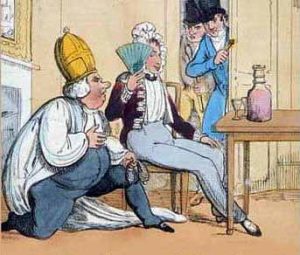

However, in 1816, Church became involved in another scandal when he was arrested on charges and this time convicted of attempted sodomy. The trial took more than a year. Upon the news of the verdict, a large crowd burned an effigy of him at his church, the Obelisk Tabernacle. Rev. Church was sentenced to two years in prison. He resumed his career as a minister after his release, and was not involved in any more scandals afterwards.

The validity of the accusations against Church is certainly questionable, as false accusations of sodomy were not unheard of. In his memoirs, radical speaker Henry Hunt recalled the supporters of his opponents frequently heckling him with remarks that suggested he was engaging in buggery. In 1811, the Lord Bishop of Clogher, Percy Jocelyn, was accused of “committing unnatural acts with another man” by a man named James Byrne. The Bishop took legal action against the accusations that he stated were false.

Given a lack of evidence to support the accusations, and considering the Bishop’s membership in the Society for the Suppression of Vice –an organization responsible for many raids on molly houses –the court sentenced Byrne to three floggings and two years in prison. Byrne nearly died from the first two floggings, so he recanted his accusation and the third flogging was canceled.

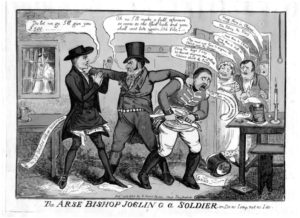

Byrne’s accusations, however, had not been forgotten by 1822, when Bishop Percy Jocelyn was caught in the act of buggering a soldier named John Moverly. The ensuing scandal, taking into account the bishop’s hypocrisy and high social standing, was so vicious that the moral superiority of every clergyman in England was called into question. The scandal reverberated throughout society. Lord Castlereagh’s suicide less than a month afterwards is said now to have been because he was being blackmailed for “preferring men.” As for the Bishop, he was fortunate to have the means to escape from England to France.

Byrne’s accusations, however, had not been forgotten by 1822, when Bishop Percy Jocelyn was caught in the act of buggering a soldier named John Moverly. The ensuing scandal, taking into account the bishop’s hypocrisy and high social standing, was so vicious that the moral superiority of every clergyman in England was called into question. The scandal reverberated throughout society. Lord Castlereagh’s suicide less than a month afterwards is said now to have been because he was being blackmailed for “preferring men.” As for the Bishop, he was fortunate to have the means to escape from England to France.

France had decriminalized sodomy in 1791, and when Napoleon created a new penal code in 1810 he carried over the entire lack of laws banning sodomy. As a result, Paris became something of a “hot spot” for homosexual and transgender individuals. No laws existed to protect them, and the behavior was certainly not accepted, but Bishop Percy Jocelyn was still able to take up residence in Paris under his own name and was welcomed into French society. Indeed, the entire French Empire was something of a different, freer experience for homosexual people than it was anywhere else in the world.

Details about life as a homosexual woman during this time period are scarce. Romantic relationships between women were — and often still are — misconstrued as passionate friendships. In cases where such friendships were discovered to have a sexual nature to them, legal action was typically not pursued against the offenders. Even if it was, the laws were much more lenient in regards to lesbian behavior. Of course, women were much less able to secure any sort of financial stability for themselves without a husband, so most lesbians chose to marry and carry out their affairs in the most secretive of ways. Only a handful (that we know of) were able to get by without a husband.

The Ladies of Llangollen were two such women — Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, who had a romantic relationship for over 50 years. Defying their families, the two established an estate in Wales, called Plas Newydd, rather than enter into marriages with men they did not love. Though they incurred significant debt in order to have a staff, they survived on the generosity of friends until a fascinated Queen Charlotte convinced King George III to grant them a pension.

The Ladies of Llangollen were two such women — Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, who had a romantic relationship for over 50 years. Defying their families, the two established an estate in Wales, called Plas Newydd, rather than enter into marriages with men they did not love. Though they incurred significant debt in order to have a staff, they survived on the generosity of friends until a fascinated Queen Charlotte convinced King George III to grant them a pension.

Plas Newydd became something of a haven for writers during the Regency era, especially since the couple living there could afford to keep it. Another, even more notable, lesbian of the time was Anne Lister, who was a guest at Plas Newydd on occasion and who kept an explicit diary (in code). She had secured a position amongst the landed gentry, having inherited a good amount of wealth and a manor in Yorkshire called Shibden Hall. Because of her position, she was able to survive securely without ever marrying a man.

Details on transgender individuals are even harder to find. This isn’t just because being transgender was such an unexplored concept at the time, but because there was a lot of cross-dressing that went on for other reasons even though it was highly illegal. There were frequently men who dressed in women’s clothing at molly houses, and these likely were male-to-female transgender folks. Beyond those, however, there were practical reasons. Were women living as men transgender, or simply trying to escape restrictive gender roles? It’s hardly a secret by now that some women entered military service pretending to be men. In 1812, two men dressed as women calling themselves “General Ludd’s wives” led an attack on a factory owner’s home — but this was most likely to obscure their identities rather than because they actually identified as women.

GAIL says: Thank you, Graham!! Fascinating info. We have come a long way from the days of the Regency, at least in some parts of the world, in how we see and treat our LGBT society members. Still a long way to go!

Blog readers, have you read any Regencies with LGBT characters? What do you think about including such historically accurate elements of the time period in stories about romance?

Great post, very interesting. A very cruel time for anyone who didn’t conform to the status quo.

Fascinating stuff! I’ve just finished a novel that will be part of my The Shaws series, about a couple of men who fall for each other, and the difficulties they face.

The terminology is dreadful! I’m writing a bit earlier than the Regency, in the 1750s, so “mollies” were specifically men who dressed as women. What we would call homosexuals were simply “sodomites.” And it wasn’t gender-exclusive, either, it was just that women were never accused of it. It appears that gender preferences were more fluid then, in practice, or it might just be that men whose preference was for their own sex married and had children to allay suspicion.

Lots of fascinating information from the later period, thank you!

Lynne, that sounds like a very challenging story to write! (but fascinating) Wishing you the best success with it!

I think it is important to give as well-rounded and accurate impression of your time period as possible.

Although earlier than the Regency, Diana Gabaldon’s Lord John Grey is a wonderful character and throughout her books she portrays 18th century LGBT issues very well.

Without wanting to give away any spoilers, there are LGBT characters in my debut novel The Murmur of Masks, which is set from 18o3 to 1815.

Ooh, sounds intriguing Catherine! And I have not read DG’s Lord John Grey –will have to put that on my list!!

Absolutely fantastic post! There isn’t enough written about this and it can still be tricky to find LGBTQ+ historical fiction, let alone historical romance. My book Artemis has a hero we would consider trans, but whether or not the reader would depends entirely on how they view historical gender identity. As you mentioned, a surprising number of women lived as men, and that has been more or less tolerated since at least the middle ages (women wishing to be men being seen as virtuous) while men dressing as women have been viewed with suspicion (or much worse). It’s an unfair double standard that’s always been with us, unfortunately. Thank you for the terrific post! I hope to see more like it and more LGBTQ+ historical fiction so we can start to put the marginalized back into history where they belong. x

Great post! Another one for my research notebook. I do have a minor character who is gay in my first full-length Regency historical romance that was just released. He plays an important role as he was the lover of my hero’s deceased brother, a duke, and the hero is being blackmailed over some explicit letters his brother wrote. The hero feels compelled to look out for the brother’s lover, to protect him from consequences which, during the Regency, could be quite dire. I had one of my very dearest friends in the world read the book to make certain he found the character believable. This particular friend is gay, black, and Catholic from Mobile, Alabama. We call him the consummate overachiever. 🙂

If you get the chance, check out anything written by Michael Robinson. I ran across an article by him when I was researching the topic of bibliomania or book collecting during the Regency. He has written a book on the topic which should be coming out soon.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/0748682457/_encoding=UTF8?coliid=IC2U7VC4EJ8UU&colid=2EKA27DDI2JA9

Ornamental Gentlemen: Literary Antiquarianism and Queerness in British Literature and Culture, 1760-1890

I have it on my wish list and I have actually e mailed the author in the hope of gaining an interview for Number One London and perhaps a chance to review the book.

I recently finished a book about the exiled owner of Kingston Lacy in Dorset who basically furnished, designed, and redecorated his ancestral home knowing he would never be able to return to see it because he was gay. It is a brilliant and heart-breaking read.

The Exiled Collector: William Bankes And the Making of an English Country House by Anne Sebba

The Exiled Collector is on my (very large) TBR pile of research books. 🙂

It is a fascinating book and so very poignant. He was a man torn by many demons, persecuted, and a good steward of his ancestral home, forbidden to him though it was.

Louisa, thanks for these book recommendations! They both sounds very interesting…. (sigh) –more to add to the TBR list!! (along with your new release!)

You are welcome, Gail! I am truly looking forward to reading the Michael Robinson book as the articles I’ve read by him have been intriguing beyond measure! And I hope you enjoy my new release. It is my first full-length novel so I am a bit nervous!

Thank you so much for visiting us, Graham, & providing us with such a great post in honor of Pride Month! (I can’t believe it didn’t even occur to me to do a Pride-related post — especially as I’m writing an m/m Christmas story right now. *heatdesk* I’m blaming this entirely on that stupid heat wave we had throughout most of June…)

In The Lily Brand, my very first historical romance, which came out almost exactly 12 years ago, I included a gay secondary couple because I was so incensed about the way homosexuality was portrayed in much of romance fiction. Luckily, a lot has changed since then, not the least the increasing popularity of m/m (though this has brought about its own set of problems). Of the Regency-set m/m historicals I’ve read, I have enjoyed KJ Charles’ Society of Gentlemen trilogy best (set during the Cato Street conspiracy, which also plays a significant role in one of the books, A Seditious Affair), as well as Joanna Chambers’ short “Introducing Mr. Winterbourne”.

I highly recommend Amphibious Thing (a biography of Lord Hervey) for a look at a powerful gay/bisexual man of the Georgian era. Society seems to have been very aware of his sexuality but his title & position paper to have insulated him (and his lover, Stephen Fox; Charles James’s brother) from the treatment that many others received.

I’m currently reading Passions Between Women by Emma Donoghue and it’s a fascinating look at lesbians and how they were viewed.

Of course there’s a typo.

Sorry Graham could not reply to any of these comments personally. He had planned to, but after he had a wonderful time in NYC attending the Pride celebration last weekend, he came home and quite promptly came down with a strep infection! Poor guy has been quite sick all week. Fortunately he had pre-written the blogpost!!

Oh no! I hope he’ll be better soon!

This was a lovely read, thank you.

It was also very helpful in my research <3

I amsomeone who i who is prejudiced against my own people and the LGBQ community due to projection. I am a hypocrtite because I enjoy kiddie porn immensely. The reason is I was molested as a chld in this life and past lives. The past life regressions took a toll on me. I am bereft. How can I have a sex change operation?

[…] Queer in the Regency: a Slice of Once-Hidden LGBT History […]