I’m into comfort TV. To me, that includes series with likeable, quirky characters who rub against each other in interesting and funny ways—series like Northern Exposure, Parks & Rec, Grace and Frankie.

I’m into comfort TV. To me, that includes series with likeable, quirky characters who rub against each other in interesting and funny ways—series like Northern Exposure, Parks & Rec, Grace and Frankie.

My most recent go-to comfort TV is an older comic mystery series called Lovejoy, which I watched on BBC while I was living in the UK. It was also on A&E.

The title character, played by Ian McShane, is a shady antiques dealer who is also a “divvy”—someone who can spot a genuine treasure amongst less valuable items. Lovejoy is the quintessential charming rogue, a bit of a con man but with redeeming characteristics. The series is based on books by John Gash (which I haven’t read) but I’ve read that the books were darker and Lovejoy less likeable.

For much of the series, he works with Lady Jane Felsham (Phyllis Logan), lady of the manor and interior decorator. They are professional partners and dear friends. There’s also an ongoing sexual tension, but they don’t end up together (and shouldn’t). He has other love interests, but it’s even stated at one point that he is more in love with the idea of romance than any one woman.

Here’s a clip of his first meeting with Jane.

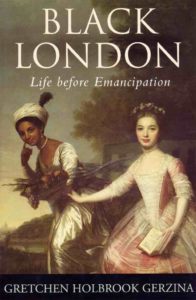

The appeal to me and possibly other Regency romance fans is more the British setting, the stately homes, the countryside, the language, and of course, the antiques. Many of the items featured are pre-Victorian so they are things Regency characters might have possessed. I can call it research!

A deeper theme is that of the genuine versus the fake. Lovejoy has a deep appreciation for beauty, history, artistry, and craftsmanship. He may scheme to make money, but it’s not just about the money. He also has that appreciation for people. His affection for Jane is, I think, in part because he recognizes that she is what an aristocrat is supposed to be: cultured and honorable. He also values good-hearted people of any social status. Sometimes he gives up profit in order to help such people. The ones he usually cheats are either shallow and pretentious or coldly materialistic—people who value antiques only for their monetary value or status appeal.

In one of the episodes he says you can’t con an honest person. I interpret this as meaning a person who doesn’t expect a deal that is too good to be true.

I like shopping at shows and stores that feature antiques, collectibles, and secondhand items, but to me, a treasure is a reasonably priced item that will make me happy when I look at or use it. Provenance doesn’t matter to me.

I’ve already blogged about my attraction for Georgian and Regency era inspired furniture. I’ve collected some nice reproductions made in the early 1900’s—elegant and better made than most new furniture is now, and I don’t mind a few signs of wear.

I feel the same way about dishes. I’m downsizing, so I want to get rid of the rarely used “fine china” set that I never really liked that much, and my rather tired everyday stuff. I am replacing it with a growing collection of mismatched, used blue transferware. I had a few pieces already and it’s been a blast to find more. Here’s a picture of my haul from the Madison Bouckville Antique show last August.

Such dishes are often reproductions of designs from the Regency through Victorian eras. They are inexpensive (I’ve been averaging about $3 a piece) and I think they look more interesting mismatched. So I can have friends over and if someone drops a plate, we can just laugh about it and I can have fun hunting down a replacement.

Such dishes are often reproductions of designs from the Regency through Victorian eras. They are inexpensive (I’ve been averaging about $3 a piece) and I think they look more interesting mismatched. So I can have friends over and if someone drops a plate, we can just laugh about it and I can have fun hunting down a replacement.

How about you? Do you like shopping for antique and vintage items and what do you look for?

Have you seen Lovejoy? What do you think of the show? What is your comfort TV?

Elena