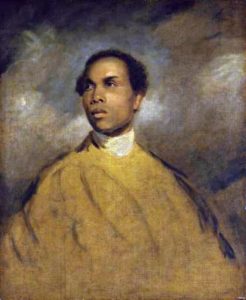

One of my favorite books to revisit when I’m trying to imagine Georgian England is Gretchen Gerzina’s BLACK LONDON. There are many free blacks from the era with whom some of us may be familiar: Francis Barber, Ignatius Sancho, Olaudah Equiano, Elizabeth “Dido” Belle, Jonathan Strong, Ukawsaw Gronniosaw. There is also the ever present black groom, footman, and page who are seen in art and mentioned commonly in letters and printed sources. What interests me most though is the thriving community of free blacks that clearly populated London. There were Africans sent directly by their families to England to learn English (mostly to further trade). There were shopkeepers, clerks, athletes, and musicians (LOTS of musicians!). Much of what we know about this community comes, sadly, not directly from them, but from their being mentioned in the news or by racists complaining about them. I’m going to quote directing from BLACK LONDON here (p.24):

“A newspaper article from 1764 refers to ‘no less than 57 [black] men and women’ who held a party filled with music at a Fleet Street pub. Dozens of black people sat in the gallery at the famous Somerset suit in 1772, and hundreds celebrated afterwards at a Westminster pub…[Philip Thicknesse] complained in 1778 that, ‘London abounds with an incredible number of these black men, who have clubs to support those who are out of place.’ In other words, not only must a viable communal network have existed, but it could be quickly and effectively mobilized for the purposes of social and political action, even at a time when their political clout seemed non-existent.”

So, when picturing Georgian London, remember black Londoners existed then as now, not in isolation, but in relation to one another and to the community at large.