Why write another post about Regency weddings? If you search this site, you’ll find a whole collection of fun & fact-filled wedding-related posts written by various Riskies over the years. But the book I’m currently working on is set against the background of a Regency wedding, and I’m reviewing everything I know about such events. I’m looking at how we know what we know as much as the “what we know” both in this post and in my research. As a former journalist, I always remember to “consider the source” when collecting information.

As romance writers, we authors can find it a bit disappointing to hear that Regency weddings were not as big and special as they tend to be today. It’s true that many of our revered traditions developed during Victoria’s reign or later. One of the oft-cited sources for documenting the “low-key” Regency approach is a remembrance by Jane Austen’s niece Caroline (b. 1805), describing her half-sister Anna’s marriage to Benjamin Lefroy on November 8, 1814.

Note the following from her recollection: “The season of the year, the unfrequented road to the church, the grey light within… no stove to give warmth, no flowers to give colour and brightness, no friends, high or low, to offer their good wishes, and so to claim some interest in the great event of the day – all these circumstances and deficiencies must, I think, have given a gloomy air to the wedding…” She adds, “Weddings were then usually very quiet. The old fashion of festivity and publicity had quite gone by, and was universally condemned as showing the bad taste of all former generations…. This was the order of the day.” (my added emphasis)

I haven’t found the date when Caroline wrote this reminiscence, but I note that she was all of nine years old at the time of the actual wedding. I find her insistence that “this was the order of the day” a bit suspect. How would she know this? She was not then at an age to be attending any other weddings. Also, it was November. I’m sure hothouse flowers were not in the budget!

She continues: “No one was in the church but ourselves (she had listed six men and four females, all relatives in the two families), and no one was asked to the breakfast, to which we sat down as soon as we got back…The breakfast was such as best breakfasts then were. Some variety of bread, hot rolls, buttered toast, tongue, ham and eggs. The addition of chocolate at one end of the table and the wedding-cake in the middle marked the speciality of the day.”

Isn’t it possible that, looking back in her later life, she might have been tempted to justify the extreme austerity of this family wedding by claiming it was the norm? Both Anna and Ben Lefroy were the offspring of clerics, and the groom was a cleric himself, as yet without a living. An expensive wedding was doubtless not an option for the family (and probably not considered suitable for clerics, anyway). A longer version of the same quote begins, “My sister’s wedding was certainly in the extreme of quietness: yet not so much as to be in any way censured or remarked upon….” Caroline sounds defensive to me, as if she feared people would judge her family against the more elaborate Victorian wedding customs that became the fashion later in the century when she was looking back.

Just eight years before Anna Austen’s minimalist wedding, we have another oft-quoted wedding example from the opposite end of the continuum that I propose existed as much then as now. The Annual Register for 1806 includes this description of a very elaborate wedding clearly designed to show off the extreme wealth of the bride:

“Sept. 9. This day was married at Slinsford Church, Dorset, Viscount Marsham, son of Earl Romney, to Miss Pitt, only daughter and heiress of William Morton Pitt, esq., with a fortune of 60,000 pounds and an estate of 12,000 pounds per annum, independent of the estates of her father.” (There follows a list of the witnesses, seven of whom were prominent enough to be named, in addition to the bride & groom and family members, plus one “officiating” attendant each for bride and groom.)

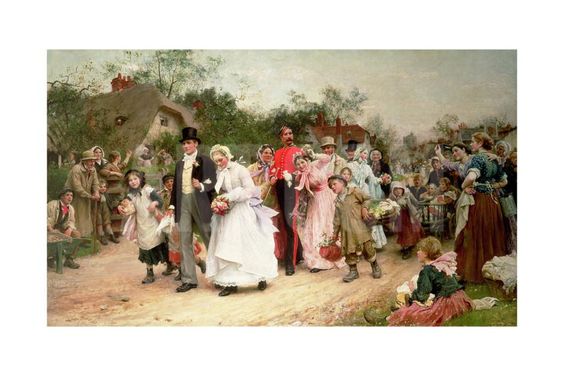

The astronomical expense lavished on this wedding would be almost unimaginable if you didn’t take into account that the ultra-wealthy aristocrats were the rock star celebs of their day. “In the early part of the morning the whole of the unmarried female branches of the neighbouring tenantry and villages attended at Kingston-house, the seat of W.M. Pitt, esq., each female attired in an elegant white muslin dress, provided for them, as a present on the occasion, by Miss Pitt. After refreshments, about 40 couples proceeded, two and two, before the procession to the church, strewing the way (before the happy couple), in the ancient style, with flowers of every description. After the ceremony they returned in the same order, attended by nearly 300 spectators, where a dinner, consisting of English hospitality, was provided on the occasion in booths on the lawn; and the festive eve concluded with a ball on the green, in which the nobility present shared in the mirth. At an early hour in the evening, the happy couple and suit set off in post chaises to pass the honey-moon at the lady’s own seat, Enchcome-house, Dorset.”

It makes me a little bit crazy when I hear people now try to characterize the behavior of people in the past as being all one particular way. I’m not saying fashions and trends didn’t exist, but individual people and families still followed their own traditions and were limited (or not) by their incomes and situations, just as we are today.

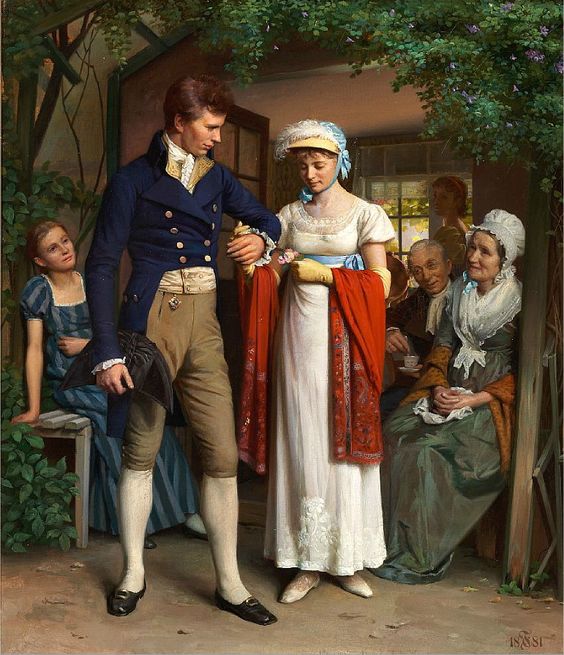

Knowing this makes me comfortable designing the wedding in my new book the way that fits my characters and their specific situations, within a good grounding in what we do know about Regency weddings. Since they’re not using a Special License, the wedding has to be in the morning, and at church. This was a matter of law, not choice, as was the presence of an officiating clergyman and a clerk to record the proceedings. There will be no white dress, veil, or assemblage of bridesmaids. Her dress could be white, but since in this period it could be any color, I think it’s more fun to go there. And while fashion prints start to show veils in the late Regency (see an interesting post here), my 1814 wedding is too early for that. A wedding “breakfast” will follow, as was customary. It makes sense that you need to feed your guests! As my groom’s family is wealthy, the breakfast will be more elaborate than the one Caroline Austen described, but nothing so grand as Miss Pitt’s! And as my bride has almost no family near her, her relatives will travel a distance to attend.

If you married, how big or small was your wedding? Or weddings you’ve attended? How big or small is your family? I’ve been to intimate weddings with less than 30 people and one huge wedding with 500 guests where I didn’t even know the bride or groom.

It’s just one more very sad ripple effect of the Coronavirus pandemic that weddings since March of 2020, if happening at all, have to be small, intimate celebrations, and preferably held out-of-doors. Circumstances require adaptation. That was as true back in the Regency as it is now, so I think assuming Regency weddings were only done in one particular way is a false view of the times. Sorry, Caroline Austen!