We’ve already covered so much in the first four parts of this series since April (see links below), but there’s one more aspect of this topic I just can’t leave out: how to store the scents that were either purchased or home-made. The fabulous perfume containers used by Regency people who could afford them are works of art in themselves, but they also served an important purpose. After all the trouble and expense of creating a wonderful perfume, what good was it if you couldn’t keep it long enough to enjoy using it?

As we saw in Part 1 about Floris (the famous 18th century London perfumery that is still in business), records show that their wealthy clients often brought in their own containers to be refilled on the premises with their custom-blended signature scent. Preserving the quality of those scents was paramount. Let’s see what some of those containers might have looked like! But let’s also consider the practicalities of the storage problem and take a quick glimpse of how past ages met the problem, too.

Scent essential oils need to be protected from four things: air, light, heat, and contamination from other scents. Perfumes combine any number of these oils, but the combined scent achieved must still be protected. A wide variety of materials and sealant techniques have been used since the earliest times to accomplish these aims.

Despite Shakespeare’s eloquence, glass was not always the most ideal choice, especially once distilling in alcohol or using a vinegar base for certain perfumes was introduced, as those substances could etch or erode the glass. Still, glass remained one of the popular choices along with types of stone (alabaster, agate, rock crystal, travertine marble, laboradite), ceramics (faience, terra-cotta, porcelain), metals (silver, gold, even copper in very early periods, and later enameled metal). Historically, scent containers have often been as much—or more–of a luxury item than the perfumes to put in them!

The Egyptians learned glass-making from Mesopotamia, and used both core-formed glass, stone and ceramics for their perfume containers. The lids or stoppers are less well-documented; they may have used wood, leather, straw or clay that did not survive the ages. The Greeks were fond of ceramic containers in shapes from nature, but also used core-formed glass. It was the Romans who invented the technique of blown-glass, and the path to modern glassware opened.

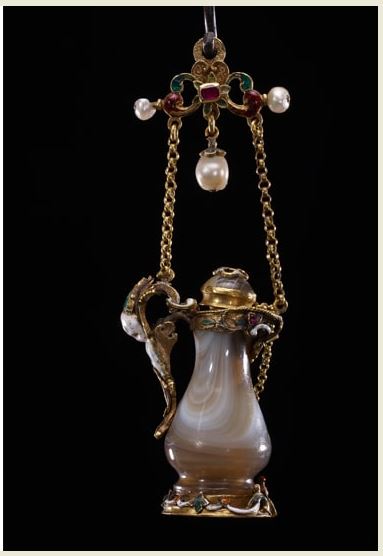

By the 16th and 17th centuries, the growing popularity of liquid perfumes meant scent bottles became more elaborate…. And by the 18th century the trends in perfume containers followed the prevailing trends in art. This means a wide variety including enamels and porcelain, but also gold and any combination of fine materials including gemstones and pearls…

1) A small scent bottle meant to be worn as a pendant, of agate, gold, and gemstones (rubies). This 17th-century bottle was added to in later years. (Photos: © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

2) Two distinctly different styles of 18th century French ceramic perfume bottles

German and English porcelain in shapes were popular, and many bottles came with their own case, which protected from breakage but also helped protect clear glass bottles from light. This “figurine” style bottle from the mid-18th century (below), is something a Regency miss might have been given by her grandmother! The auction description notes: “2¾in (7cm) long Derby porcelain perfume bottle and stopper, decorated with a striped cat pursuing two turtle doves up a tree, the base with a seal of a prancing horse and angel. In a shaped leather case”

Elsewhere I found mention that “[perfume bottles] began to be produced in cut glass patterns in the Georgian period, whereupon they were sold in fitted plush-lined cases…. Typically, scent bottles in the 19th century were crafted out of cut glass and then topped off with silver lids. These early glass examples were often made in a flask-shape, and featured a fine chain for suspending them on a chatelaine.”

The pair below have gold tops, which probably cover a smaller glass stopper inside with a ground glass shank to make it as air-tight as possible. (Cork was never used, because it has an odor of its own that could corrupt or contaminate the original perfume in the bottle.)

Ground glass stoppers seem to have been in use from quite early –that’s a side rabbit hole I did not successfully navigate! But at times both the stoppers and the bottle necks might have been covered with animal membrane or vegetable parchment to improve the tight fit, and an outer cap of white glove leather could have been added, as protection from evaporation.

Pendant-style mini-perfume bottles that could be worn (or carried in one’s reticule) continued to be popular throughout the 19th century.

A few more examples of Regency-era bottles that reflect the changing taste of the times:

1) an “Empire” brass and crystal perfume bottle. The French particularly favored crystal and cut glass.

2) an oval Louis XVI perfume bottle in gold and enamel decorated in a similar style as pocket watches and snuff boxes of the period often were, “the blue ground inset with a grisaille portrait, and classical figure on the reverse” with jewels (real or paste) decorating the stopper and borders.” (auction description) Note: the gold metal top is probably not the “stopper” but a removable lid/cover that protects and helps to hold the stopper in place. It is probably glass. Such lids often had a chain to keep it attached to the bottle.

3) this one is made of rock crystal with elaborate gold casing.

Two examples of enamel work: (left) an “18th century Bilston (South Staffordshire) pear-shaped enamel perfume bottle, with topper and chain” and (right) German, also 18th century and formed like an actual pear.

As the 19th century progressed, perfume bottles became another medium for designer artwork and styles became identified with particular perfume brands. But the market also opened up for less expensive perfumes and customers with far more modest incomes, so perfume containers had to be created that would still be attractive and perform the necessary protection while costing less. Today’s perfumes are far less volatile because of the synthetics used in them, but they are still subject to evaporation due to the alcohol content. Wouldn’t you love to have perfume in a fabulous container like some of these beautiful old classics?

In this series I have introduced you to the fascinating world of Regency perfumery, but by necessity I have left a great deal unexplored. Vinaigrettes, for instance. Scented vinegars (aka “toilette vinegars”) were made by combining scent essences with white wine vinegar—rose, for example, or essence of orange-flowers. Smelling salts were developed with the discovery that ammonia crystals, mixed with certain compatible scents, lasted much longer than the liquid variety of smelling bottle or vinaigrette with a soaked sponge. Scents related to rose, nutmeg and cinnamon were recommended. One recipe I saw also used bergamot, lavender, and clove in addition.

I also didn’t talk about all the various kinds of products that were scented in the 18th and 19th centuries. All kinds of toiletry items, of course, including “Venetian chalk” (face powder) and freckle lotions, but my favorites are the items like scented writing desks, sewing baskets, and various boxes for storing other items. How did they make the scent last? These items had no space to accommodate the actual source of the scent.

They did it ingeniously: a piece of very thin leather, such as chamois, or heavy blotting paper was soaked in the desired perfume and then additionally treated with the scent, allowed to dry, and then was encased in a very thin silk cover, creating a sort of “perfume skin.” This could then be inserted into a desk pad or incorporated into the cover of a sewing basket, stationary or handkerchief box lid, or placed amidst sheets of stationary. They also used perfumed pastes to rub scent into leather goods like belts or other items.

To read more:

Candice Hern’s website has four separate articles worth reading, and she includes good bibliographies:

Other articles online (there are many more):

https://www.acsilver.co.uk/shop/pc/scent-bottle-history-d129.htm

Books:

Edmund Launert, Scent and Scent Bottles, Barrie & Jenkins, 1974.

Heiner Meininghaus and Christa Habrich, Five Centuries of Scent and Elegant Flacons, Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 1998.

I highly recommend the following, both of which are available from Googlebooks:

Eugene Rimmel, The Book of Perfumes, London: Chapman & Hall, 1867

The Toilette of Flora, London: J. Murray and W. Nicoll, 1784

I sincerely hope you’ve enjoyed this series! A deep dive down a rabbit hole, but the exploration has been fun. Here are the links to the other four articles in the “Smelling Sweet in the Regency” series and the dates they appeared here at the Risky Regencies blog:

Part 1: Beyond Floris April 12, 2021

Part 2: Beyond Floris part 2 (Stillroom Magic) April 26, 2021

Part 3: Making Sense of Making Scents May 10, 2021

Part 4: The Art of Mixing Scents, Scents for the Sexes, and the Truth about Bay Rum May 24, 2021