Over the weekend, a friend asked for my handout from the Regency Refreshments workshop I did a few years ago. After digging it out for her, I thought I’d share something for Thanksgiving.

When I had the idea to give a Regency Refreshments Workshop, I thought it might be wise to begin experimenting with recipes early. My experience with making food for re-enactments has taught me that it often takes several attempts before something satisfactory is achieved, mostly because period recipes are so vague (few precise measurements combined with instructions like “bake in a slack oven” means that it’s easy to get it wrong).

I started looking through period cookery books, and found that quite a few of the recipes were familiar: Gingerbread, Puffs (meringues), Pound Cake, Macaroons. Others were familiar only because of trips to England or from books: Sally Lunn Buns, Bath Cakes, Blanc’mange. Some had seemingly familiar names, but upon closer inspection bore little resemblance to the modern dish bearing the same name: Cheesecakes, for example. Georgian “cheesecakes” (sometimes called Maids of Honour) are baked inside a puff pastry shell, rather like a modern Danish. And some have a colloquial English-ism to them that might elude a modern American reader, such as Plum Cake. “Plum” means “currants” or “raisins”, not plums or prunes as one might assume. I had certainly always pictured a sticky, sweet cake, not a dry little cake filled with currants.

And then there’s the fact that my goal here is slightly different than the one I usually have when cooking for a re-enactment. Normally, I’m attempting to make something period that appeals to a modern palate. Here, I’m trying to recreate the period flavors as accurately as possible. A new and challenging twist, sometimes requiring a bit of real hunting when it comes to ingredients . . .

The first thing I did was gather numerous extant period cookbooks. This was easy thanks to Google Books. With a plethora of options, I quickly found I had to limit myself. So I randomly chose three books to concentrate on, making forays into other sources only when my main selections failed to deliver at least two recipes for the dish being studied.

The first is The English Art of Cookery, according to the Present Practice; being a Complete Guide to all Housekeepers, on a Plan Entirely New (1788) by Richard Briggs, “many years cook at The Globe Tavern, Fleet-Street, The While Hart Tavern, Holborn, and Now at The Temple Coffee-House.”

The second is The Universal Cook; And City and Country Housekeeper (1806) by Francis Collinwood and John Wooliams, “principal cooks at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand—late from the London Tavern.”

The third is A Complete System of Cookery, On A Plan Entirely New; Consisting of an Extensive and Original Collection of Receipts, in Cookery, Confectionary, etc. (1816) by John Simpson, “cook to the late and present Marquis of Buckingham.”

I also consulted Mrs. Beeton’s Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery (1864 edition), Lobscouse & Spotted Dog: Which It’s a Gastronomic Companion to the Aubrey/Maturin Novels by Anne Chotzinoff Grossman and Lisa Grossman Thomas (ISBN: 0393320944) and Tea With Jane Austen by Kim Wilson (ISBN: 097212179X). I figured if they’d already done the legwork, why do it all over again?

One thing which I think you’ll notice right away is the enormous amount of time most of these recipes would have taken to prepare under period circumstances (i.e. no electric mixer and no gourmet grocery in which to procured the basics). Many of the cakes take several hours just to beat the batter. And quite a few recipes require you make a basic ingredient first, be it gelatin or boiled down citrus fruit or blanched almonds. And then you still have to grate and shift the sugar (which comes in solid cones). Odds are your heroine is not undertaking to make her sweetie a cake while they’re stranded alone in a hunting box (unless it’s a ruse to avoid him!).

Seed Cake

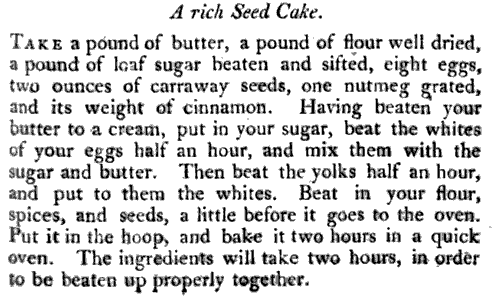

Seed cake seemed just different enough from pound cake that it was worth making on its own. The variations are also quite different from one another. The 1788 one calls for yeast and allspice, while the 1806 one is leavened only with eggs and has spices similar to those in the pound cake recipes. The 1816 book has no recipe for “seed cake”, but it does have one for “savory cake” which is very similar in its general make up, except that it does not call for any spices or seeds

The Universal Cook (1806):

Since I have a modern kitchen with a Kitchen-Aid Mixer®, I chose to make the “rich” version. It also seemed to me that this version would be the most dissimilar to the pound cake in texture. I made this cake up following the directions from 1806 to beat the egg whites and egg yolks separately. It appeared that all this beating in of air would add loft to the cake (as with a sponge cake). What I missed in my initial reading was the fact that after you’ve gone to all the trouble of beating in air, you beat the batter some more when you combine the eggs with the butter and sugar, and then some more when you add the flour. All that beating knocks the air right out of the egg whites.

Just for comparison’s sake, I made up a second batch which I mixed in a more “pound cake-like” manner (cream butter and sugar, beat in eggs one at a time, add everything else and call it a day). It came out exactly the same as the one I took all the trouble to do in stages. So the recipe I’ll share with you is the easy version:

1 cup unsalted butter, softened

3 cups flour (not self-rising)

2 cups sugar

5 large eggs

1 TBL allspice

1 oz caraway seeds

Preheat oven to 350° F. Coat your pan (almost any kind of baking dish from a bunt to a spring mold will work) with a LOT of Baker’s Pam® or similar product.

Beat together butter and sugar until pale and fluffy. Add eggs 1 at a time, beating well after each addition. Reduce speed to low and add half of flour. Add the allspice and caraway seeds. Then add all of the remaining flour. Beat for 3-5 minutes, until well combined and satiny. Pour batter into pan and rap pan against work surface once or twice to eliminate air bubbles.

Bake until golden and a wooden pick or skewer inserted in middle of cake comes out with a few crumbs adhering (about 1 hour). Remove from oven and invert onto the rack to cool.

Serve with a period sauce (wine sauce is great with it) or with something like Devon triple cream. It needs something to give it a little moisture. It goes great with an digestif wine like sherry, port, or Madeira.

My friends’ reactions really ran the gamut: some loved it, some thought it would have been better with poppy seeds or cardamom* (and I agree, those flavors would have suited a modern palate much better than the caraway seeds), some hated the anise flavor, I thought it had a slightly medicinal flavor, but wasn’t unpleasant, especially with a glass of sherry. And it tastes even better the next morning and goes great with a cup of tea.

The bottom line is that it turned out to be a slightly dry, very dense, not too sweet, caraway-flavored, cake.

*I do find cardamom used in period recipes, but never in cakes. It always seems to be in cordials and the like for the sick room. Same with poppy seeds.