In Jane Austen’s Emma, when Mr. Woodhouse goes to Donwell Abbey as part of the strawberry-picking party, he is ensconced inside with Mr. Knightley’s collections.

Mr. Knightley had done all in his power for Mr. Woodhouse’s entertainment. Books of engravings, drawers of medals, cameos, corals, shells, and every other family collection within his cabinets, had been prepared for his old friend, to while away the morning; and the kindness had perfectly answered. Mr. Woodhouse had been exceedingly well amused. Mrs. Weston had been showing them all to him, and now he would show them all to Emma; fortunate in having no other resemblance to a child, than in a total want of taste for what he saw, for he was slow, constant, and methodical.

Chapter 42

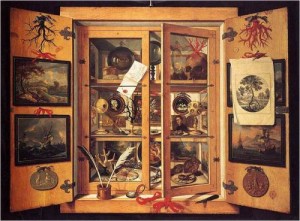

These cabinets of curiosities, or Wunderkammern appear to have become popular in the 16th century and proliferated throughout Europe. Collectors were typically encyclopaedic in their approach, and the cabinets contents were items thought to be exceptional, rare, and marvellous. The items Jane Austen decribes- drawers of medals, cameos, corals, shells, and every other family collection within his cabinets– were typical of the sort of items which made their way into such collections.

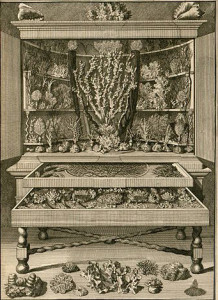

Below is a description of the Cabinet of Curiosities assembled by the famous Tradescant family, gardeners to the Cecil family of Burghley. This cabinet became known as the Ark and was opened to the public, forming the basis of the Ashmolean Museum:

To be ‘curious’ was a compliment in Elizabethan/Jacobean times and both Tradescants became famous for gardening, design, travel and their collection of curiosities. The epitaph on their tombstone describes very well why they became well known, and the interest there is today in their activities. This can be read today on their tomb at the museum.

The John Tradescant the Elder first travelled after 1609 when he entered the service of Robert Cecil who became the first Earl of Salisbury. He visited Europe to bring back plants and trees including roses, fritillaries and mulberries to the gardens at Hatfield. Later, in the service of Sir Edward Wotton, Tradescant accompanied a diplomatic mission to Russia, and he also visited Algiers, always taking botanical notes and gathering plants. By the 1620’s Tradescant had achieved a prominent position as a director of gardens whose advice was sought by the highest in the land.

In 1626 Tradescant leased a house in Lambeth where he developed his own garden and a cabinet of curiosities where he displayed ‘all things strange and rare’ that he brought back from his travels. The original is in the Ashmolean, and a copy is on display in the museum. Tradescant’s home came to be called ‘The Ark’ and was an essential site to see in London at the time as more was being learnt about the world and different cultures. It was the first museum of its kind in Britain open to the public, charging 6d admission…

At the suggestion of Elias Ashmole, he began to catalogue the collection at the Ark, and the Musaeum Tradescantianum of 1656 was the first museum catalogue published. Tradescant willed that the collection was to go to his widow on his death, but Elias Ashmole obtained the collection by deed of gift and established the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford with the collection. Some of these original items can still be seen in that museum and Ashmole is also buried at the Museum of Garden History. The tomb of the Tradescants stands beside the knot garden near that of Captain Bligh of the Bounty, and is covered in carvings representing their interests in life which marked them out as curious men.

Trawling Google seems to indicate a fairly wide range of interests, collections, and types of cabinets. I’ve been trying to imagine what Mr. Knightley’s might look like. I think it’s probably not very like Peter the Great’s tooth collection. And the description indicates it’s probably broader and more eclectic than 1715 illustration above. I think of it as a smaller version of the Tradescant’s collection, accumulated through the generations of Knightleys at Donwell Abbey but perhaps collected a little closer to home than the contents of the world-traveling Tradescants’ cabinet.

I picture it more like the more carefully organized drawers and shelves pictured in the Mark Dion designed cabinets from this century. A tad more grand than a messy box of interesting items.

What’s in your cabinet?

tumi ショルダーベルト