Did you ever want to go up in a hot air balloon? Have you ever done so? I always wanted to. In Rhode Island where I live, July used to always bring with it the annual “balloon festival,” held in the fields on the campus of the University of RI. On a hot sticky day we would always go to admire the fabulously bright and beautiful inflated balloons tethered to the ground until good flying conditions came around at the end of the day, usually around 6pm when the air would go still for an hour or two.

During the day, people would pay to go up a short way in the tethered balloons, but oh, those 6pm flights! The balloon crews, and sometimes a paying guest or two, would be set free to go up, up and off into the distance, with their “chaser” vehicles in hot pursuit to find them when they landed.

I imagine the festival atmosphere with all the vendor booths surrounding the area where the balloons were on display and the crowds of admiring, curious people was not too different from the way things were back in the late 18th century and Regency years when balloon events were extremely popular attractions, often attracting very large crowds.

We’ve touched on this topic briefly before now. Two years ago when we were celebrating amazing Regency women during Women’s History Month that March, we included Sophie Blanchard in our list, with the following very short bio:

Sophie Blanchard (1778-1819)- Napoleon’s official balloonist and aerial advisor, she was the first woman to pilot her own balloon and the first to make ballooning her career. She began as the wife of Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the world’s first professional balloonist, and continued after he died (in a balloon accident) just five years after she started. She became extremely famous throughout Europe and often performed in Italy. She performed 67 balloon ascents before she was killed in a balloon accident at the age of 41.

Also, Risky sister Elena Greene’s book, Fly with a Rogue (published in 2013) has a balloonist hero. It’s a great story –not your run-of-the-mill Regency. (If it were, it wouldn’t be “risky,” now, would it?) And just BTW, the ebook version is 99 cents right now, as are all of her ebooks, I think! https://www.amazon.com/Fly-Rogue-Elena-Greene-ebook/dp/B00DSRJDAU/

But I wanted to come back to Sophie, and actually some other balloonists who competed with her, including other women, for they are a fascinating bunch!

Ballooning with human occupants first began in France in 1783. Jean-Pierre Blanchard made his first ascent months later in March of 1784. Later that year he moved to England, where he made several flights in London, and in 1785 he became the first to fly across the English Channel to France. He then began a tour of Europe.

Sophie married Jean-Pierre Blanchard sometime between 1794 and 1804. By the time of their marriage her husband, more than twenty years older than she was, had already abandoned his original family and become internationally famous, having demonstrated ballooning even America. Just four years later, he had a heart attack while ballooning, fell from his balloon, and ultimately died in 1809. Sophie, an international celebrity herself, continued her ballooning career for 10 more years until her own tragic, accidental death.

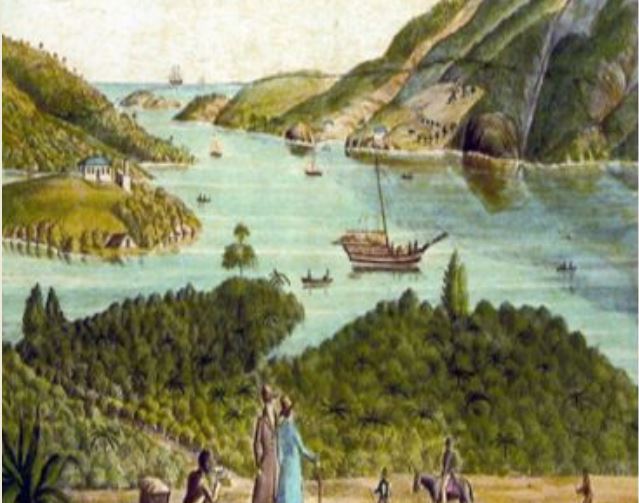

But in 1804, Napoleon had named her to replace André-Jacques Garnerin, who had been his official “aéronaute” and minister of ballooning. It was through Garnerin that I learned about the other women aeronauts who competed with Sophie, for they were members of his family. I can’t resist rabbit holes, and when I first saw this print, I had to learn who this balloonist was! This was not the Blanchards, so who was the woman?

It turns out that the “Physicien Garnerin” labeled in the print was actually the physician’s brother, Andres-Jacques Garnerin, who had gained fame not only as a balloonist but for creating the frameless parachute and using them in his balloon performances. There was also a third, older brother, Jean-Baptiste-Olivier Garnerin, involved in ballooning. A family affair!

In short order, Andres-Jacques married his female ballooning student, Jeanne Geneviève Labrosse (1775–1847). Under his tutelage she had already been one of the earliest women to fly in a balloon (10 November 1798) and the first woman to parachute (12 October 1799).

While Andres-Jacques still had Napoleon’s favor and was the official “aeronaut” for France, he and Jeanne toured in England during the Peace of Amiens (1802-03), hurriedly returning to France when the war resumed.

Their niece Elisa Garnerin, the physician brother’s daughter, learned to fly balloons at age 15 and also mastered the parachute jumps for which the Garnerins had become so known. She was the second woman in history to make a parachute jump. Elisa was ambitious, sometimes a bit unethical, and often ran afoul of the police, who didn’t like her to begin with because of the great, unruly crowds she attracted. But she made 39 professional parachute descents from balloons between 1815 to 1836, competing directly with Sophie Blanchard during the early years of her career, and she lived to the age of 62.

But wait! Neither of these Garnerin women are the young woman in the print above. That young woman, known only as Citroyen Henri, had her fifteen minutes of fame (well, a few days, at least) in 1798, when she was chosen to be the first female passenger in a controversial balloon ascension Garnerin planned to hold in the Parc Monceau in Paris that July. While the public generally favored the project, the police and government officials didn’t believe the woman knew what she had agreed to, feared what physical effects the heights might have upon her, and also claimed moral implications for the close enclosed proximity in the balloon’s basket. Eventually they agreed however.

Wikipedia says, “By all accounts Citoyenne Henri was young and beautiful.” On July 8 Garnerin, not one to miss a chance for showmanship, took “several turns around the park” with her to the applause of the crowd before they climbed into the basket of the balloon. When the ascension finally took place, they rose high into the air and covered a distance of nearly 20 miles to the north of Paris. Citoyenne Henri was famous for a short while after this feat, but is not known to have ever repeated it. She fell back into obscurity except for her connection with this historic moment in time.

Would you have wanted to be chosen to try something so new, adventurous and possibly dangerous? I have to believe that all of the “aeronauts” who flew in balloons and made descents using parachutes loved some aspect of what they did, besides the fame and money they earned. Among those who did it, the percentage of those who died in ballooning accidents is high, including both of the Blanchards.

There’s a woman who is making a full-length independent documentary about Sophie Blanchard. It’s all animated, even though it includes interviews with historians, etc. I’m fascinated now and want to see it! She’s raising funds for the finishing production costs. I wish I was rich –I’d totally help her out! Here’s the website link if anyone’s interested: https://fantasticflightsmovie.com/

There is also a movie, “The Aeronauts” based on true events from 1862 –a Victorian era scientific balloon flight in which meteorologist James Glaisher and professional aeronaut Henry Coxwell almost died after reaching more than 30,000 feet. Of course, for the fictionalized movie, they replaced Coxwell’s character with a woman. The leads are played by Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones, and you can watch it on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rm4VnwCtQO8