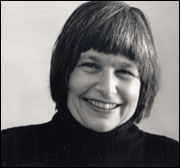

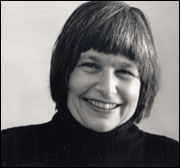

We’re very pleased to welcome as our first guest Pam Rosenthal, writer of historical erotic romance and erotica, and a frequent visitor to this blog.

“Where are the really sexy, well-written novels for grown-up, sophisticated readers? At long last, I found one…” The Contra Costa Times on Almost a Gentleman

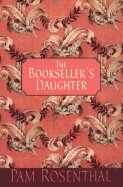

“…a love story about people who love books nearly as much as each other.” Romantic Times BOOKClub on The Bookseller’s Daughter

“…will send genteel readers into seizures… adventurous, different, and unconventional.”Mrs. Giggles on A House East of Regent Street in Strangers in the Night

Welcome to the Riskies, Pam. In one of your comments on Risky Regencies, you said you came to write romance by an indirect route. What was that, and what appealed to you about the genre?

I came to romance from erotica — which wasn’t so well trodden a path a few years ago as it is now. I’m the author of one of the books Janet recommended as a year-end favorite. Some of you might remember the one with the bare-assed cover — CARRIE’S STORY, by Molly Weatherfield (and thanks, Janet, for bringing down the tone so eloquently).

I came to romance from erotica — which wasn’t so well trodden a path a few years ago as it is now. I’m the author of one of the books Janet recommended as a year-end favorite. Some of you might remember the one with the bare-assed cover — CARRIE’S STORY, by Molly Weatherfield (and thanks, Janet, for bringing down the tone so eloquently).

It’s a very explicit and (imo) rather witty book — Carrie yacks non-stop in a mordant intellectual chicklit voice — which, given all the heavy doings she’s subjected to, is my way of making the SM subgenre poke fun at itself, while also poking fun at myself for my fascination with the SM subgenre. And which must have worked (I’m proud to say that CARRIE’S STORY is in its ninth printing and sometimes called a “classic”), leaving me to wonder how in the world I’d brought my mild-mannered self to such a pass.

So I started reading about the history of erotic writing. And discovered THE FORBIDDEN BEST SELLERS OF PRE-REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE, by the historian Robert Darnton. From which I learned that smut and enlightenment philosophy were both smuggled into France and sold surreptitiously by booksellers during the years before the revolution. The smut/enlightenment combo seemed right up my alley, my husband’s a bookseller, and the smuggling angle led me to believe there was a historical romance in there. And there was — THE BOOKSELLER’S DAUGHTER.

As for what appealed to me about the romance genre — this was sort of weird, because I hadn’t read any romance in a long time. But I knew how popular it was and I was especially curious about the bodice-ripper covers I’d been seeing during the preceding years. And somehow I was sure (correctly, as it turns out) that since I’d grown up in the Technicolor fifties surrounded by exuberant HEA mythology, my fantasies were quite romance-inflected already.

How did you get interested in the Regency period and what do you like best about it?

I was so naïve a first-time romance writer that I didn’t know how unpopular a venue France is (or was, with romance readers — I think they’ve lightened up now). But I’d had such a good time writing THE BOOKSELLER’S DAUGHTER that I didn’t want to stop writing romance — and if Regency England was the historical venue of choice, so be it and I was happy to reacquaint myself with Jane Austen.

I don’t have any smart takes on the period — yeah, it’s the clothes for me too. The men’s coats, the tight pants, the boots. Georgian architecture. Adam rooms. Wedgwood. I think of all that poise and balance as coiled-up energy waiting to burst forth as the industrial revolution and the nineteenth century British Empire.

I don’t have any smart takes on the period — yeah, it’s the clothes for me too. The men’s coats, the tight pants, the boots. Georgian architecture. Adam rooms. Wedgwood. I think of all that poise and balance as coiled-up energy waiting to burst forth as the industrial revolution and the nineteenth century British Empire.

I would say I’m attracted to the wit of the period, but I suspect that all periods have their great wits (hey, the soggy, earnest Victorians had Thackeray and Lewis Carroll). I think it’s interesting, though, how genre writers — historical and contemporary — seem to need some modicum of wit, to provide concision, momentum, a way of being modest, tough, reliable good authorial company.

And then there are ways in which I don’t like the Regency at all, for its snobbery and political reaction. Which is also a good reason to write about a period — a love-hate relationship can be an extremely productive and interesting one.

Tell us about your next book [Signet Eclipse, Sept. 2006].

It’s another sexy Regency-set historical. But this is the first of my historical books built around an actual event rather than made-up murder and mayhem. The Pentrich Revolution of 1817 was a genuine popular uprising — well, it was genuine and it wasn’t, because it was fomented in large part by an agent provocateur, in the pay of the Home Office.

My heroine and hero, Mary and Kit, run athwart of the provocateur plot on the way to solving their own problems. They’re already married, though they were legally separated before Kit marched off to fight Napoleon — but needless to say they’re still deeply, hotly, and most confusedly and contentiously in love. The erotica is quite explicit, but I think what I most enjoyed doing was the contentiousness, the way they argue at the slightest provocation, jostle for physical space and interrupt each other in mid-sentence because they know each other’s speech rhythms so well. There’s something delightfully provocative (half dance, half pugilism) about watching two people who know and love each other go for the jugular.

But until it’s listed in the publisher’s catalog, I’d better not announce the title because they could always change it.

Which of your books is your favorite?

Right now the current one, because learning the history was a challenge and an entertainment. My husband and I visited the region where it happened and also spent a day in the National Archives at Kew, reading the Home Office papers — correspondence between magistrates, spies, the provocateur, and Lord Sidmouth, the HO secretary. These were microfiches of the originals, in very scrawled handwriting — the immediacy of the past gave us goose bumps.

But I’d also like to give a nod to SAFE WORD, the Molly Weatherfield sequel to CARRIE’S STORY. May I quote to you what an Amazon reviewer said about it? “I loved this book. Not just as porn, but as a real book . . . it made me rethink all those [SM] myths, and the impact that their beauty and their despair had on my own self-view. I don’t know how I can say more about a book than that.”

And (since I did a lot of rethinking in order to write that book) I don’t know how an author could want more from a reader’s response.

What do you like to read?

Mostly fiction, literary and not-so-literary both. Within that mixed bag, I think I’ve been looking for a certain kind of story since I got my first library card. The librarian of our local branch asked if I liked “family stories,” and I, being six or seven at the time, nodded dumbly, never having considered that there was any other kind of story.

And in fact I do like stories that situate people in a nexus of relationships foregrounding the familial ones. I worked hard to create an extensive familial world for Mary and Kit, who first came to consciousness of each other as children of rival Derbyshire landowners. So it’s not just a political world they learn to situate themselves within — it’s the continuing presence of their pasts and their families.

Books that I loved for this reason last year were all (coincidentally, I think) written by way-smart Englishwomen: ON BEAUTY by Zadie Smith, WIVES AND DAUGHTERS by Mrs. Gaskell, and DEDICATION by Janet Mullany. Runners-up (also by Englishwomen as it happens) were by new-to-me authors Penelope Fitzgerald and Mary Stewart — and the latest HARRY POTTER was pretty nifty too. I also was happy finally to read way-smart Englishman Nick Hornby: I loved A LONG WAY DOWN and his essay/book chat collection, THE POLYSYLLABIC SPREE. The American wild card in the deck was Truman Capote’s gorgeous, distressing IN COLD BLOOD.

How do you do your research?

Well the unvarnished truth is that my husband Michael is doing increasingly more of it, since he jumped in when I needed him for this last book, to shed some light onto the darkness of British post-Waterloo domestic espionage. He’s been a bookseller all his life; he’s got a wide knowledge of what’s in print and a sharp professional instinct for what people will enjoy and what they need to know. So when I needed to understand how the British Home Office was spying on Britain’s parliamentary reform clubs (or for that matter, what the parliamentary reform clubs actually were), he found the resources for me and traced the references to the boxes of Home Office microfiche at the National Archives . . . I’m very grateful. Of course, we’re only starting to learn how to work together, but this last research trip to England — hiking around Derbyshire, finding the site of the Pentrich uprising, and reading those amazing documents — was our most fun vacation ever.

Oh, and he also writes my synopses — or takes my drafts and turns them into readable synopses (he wrote up his hints for synopsis-writing and I’m going to post them on my web site). I do write the novels, though. Honest.

What are you working on now?

I’m still finishing up the current one. My ideas for the next are still pretty embryonic.

Do you feel that your erotica is related to your romance writing? How?

I have the same attitude about physical sexuality in both cases. Which is that it’s less about body parts and more about how lovers see and know and understand themselves and each other in time and space. Which isn’t to say that I don’t write very explicitly about body parts or voyeurism or fetishism or bondage or any of those good things. But I do try to think how this particular pair of lovers in this particular situation will eroticize or fetishize or play domination games or get creative in bed.

The difference is that in the erotica, love wasn’t a given. I did have a sort-of hero and heroine, but they were each involved in a series of very baroque SM situations, and it wasn’t a given that they’d be together by the end of the two-part series — in fact I truly wasn’t sure how it would end until I was well into the second book. Of course I learned that when you put a lot of gorgeous people into a lot of hot situations some of them will, shall we say, conceive tendres for each other. Love made its way into those books whenever and however it wanted to — in certain cases I found myself most pleasantly surprised (and this was one of the things that made me think I could write a romance). The CARRIE books are about love, as it happens, even if obliquely.

And I think I brought something of that to the romances. A curiosity about voyeuristic and fetishistic psychology developed my skills with point of view. I like to keep it fluid and yes, sometimes oblique. I like to have minor characters take on the burden of narrative from time to time, I like to flash onto their stories, and I’m trying to learn how to make my main and subplots interact a little more. I find it sexier and more democratic that way.

In your romance books, were you aware that you were taking risks? In retrospect, what can you see that was risky about them?

Aside from the risk of saying on these august pages that there are ways I quite dislike the Regency period? Or of exposing my most cherished and fraught sexual fantasies? Or the risk of seeming preachy, along the way to presenting an episode of popular rebellion?

Well sure. All risk all the time. I mean one spends so much time (and I’m slow) writing a book that says, in one way or another, I think this is hot or I think this is interesting. And then a reader comes along and says you think what? Making one feel like a total idiot. But isn’t the risk the point of the thing? I hate roller coasters, but I seem to like putting myself through something very similar when I write a book.

I don’t have any smart takes on the period — yeah, it’s the clothes for me too. The men’s coats, the tight pants, the boots. Georgian architecture. Adam rooms. Wedgwood. I think of all that poise and balance as coiled-up energy waiting to burst forth as the industrial revolution and the nineteenth century British Empire.

I don’t have any smart takes on the period — yeah, it’s the clothes for me too. The men’s coats, the tight pants, the boots. Georgian architecture. Adam rooms. Wedgwood. I think of all that poise and balance as coiled-up energy waiting to burst forth as the industrial revolution and the nineteenth century British Empire.