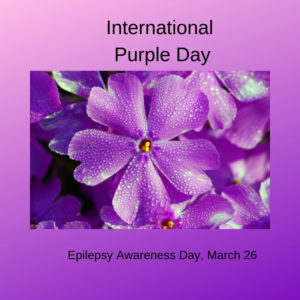

In Regency times, “The Falling Sickness” was the name given to epilepsy, which was recognized but little understood at the time. That’s hardly any wonder, for the condition has been recognized and misunderstood going back for something like 3,000 years. Since I researched and wrote a character with epilepsy in my 4th Regency novel, An Unlikely Hero, I wanted to post today in recognition of International Purple Day (and not because that’s my favorite color). #InternationalPurpleDay is the annual day set aside to raise awareness of #epilepsy world-wide. Are you wearing purple today?

The first known description of an epileptic seizure was found in a text from ancient Mesopotamia. Predictably, the cause was considered paranormal, blamed on the influence of their Moon god. Possession by demons or spirits has been a common explanation throughout history, and epilepsy has frequently been treated as a form of insanity. Influence of the moon has long been associated with it, and the terms “moon struck” and “lunatic,” deriving from that, helped to support the insanity diagnosis.

The Greeks called it the “Sacred Disease” and associated it with genius (and lunacy), but still ascribed a divine cause. Good old Hippocrates, however, tried to debunk that, identifying it as a medically treatable disease of the brain that furthermore had a genetic component. Not bad for the 5th century BC. He called it the “great disease” and the term for “grand mal” seizures comes from the French version of his term. But of course, for many more centuries no one listened to him.

People fear what they don’t understand. Even into the 18th century, they thought epilepsy was contagious, even while superstitious explanations for the cause continued. Laws addressed epilepsy –from the earliest Code of Hammurabi that said slaves with epilepsy could be sent back to their seller if a seizure happened within a certain return period, to laws in the U.S. and many other countries that forbade epileptics to marry, required them to undergo sterilization, and even set up “colonies” to separate them from society (supposedly to “help” them).

The first medical treatment for epilepsy (potassium bromide, essentially a sedative) wasn’t offered until the Victorian era, c. 1855. But at least it was the beginning of a search for treatments and a change in attitude from the days of assuming “evil spirits” were at work. However, those marriage laws, laws that prevented epileptics from having driver’s licenses, and many other forms of discrimination have continued until modern times. Misunderstanding and prejudice still continue today.

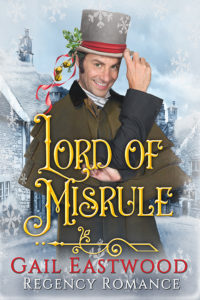

Who would put an epileptic character into a romance novel? I would. I write “sweet” romance, but I’m “risky” in other ways. I like to follow roads less taken. I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to reveal that the heroine’s twin sister in An Unlikely Hero has epilepsy, and much of the plot outside of the main romance hinges entirely on attitudes about her illness. From the father who tries denial to the aunt who thinks Vivien should be able to just stop doing it, they reflect unaccepting attitudes that still happen today. The fact that in the Regency period the wrong husband for Vivien would be able to just lock her away in an insane asylum for life looms large over the sisters’ activities, and social attitudes give leverage to the villain who… well, let’s not give everything away.

International Purple Day is important. Bringing epilepsy out into the light so people will understand and accept it instead of fearing it helps to change social attitudes. Did you know that the last of the 17 U.S. states that forbade epileptics to marry only repealed their law in 1980? Did you know that the trendy Keto diet was first developed to try to help epileptic children? Or that 1.2% of the population (3 million people) in the U.S. (or 1% in Canada) have epilepsy?

When Signet NAL published An Unlikely Hero (in 1996), a friend wrote to me and told me she cried when she finished the book. She had grown up with a father who had epilepsy and had to hide it in order to keep his driver’s license and his job. I can barely begin to imagine the stress of having to live like that, but I tried to capture some sense of it when I wrote my story. A reissued (but not re-edited) version of An Unlikely Hero is available as an ebook from Penguin Random House, in case you are inspired to check out the story.

Have you read other works of fiction that included characters with epilepsy? How do you feel about including health issues like that as part of a romance? I hope you’ll let me know in the comments!