Romancelandia thrives on strange pets, but the creatures authors give their characters are by no means stranger than those real people kept during the Georgian era. There was a large menagerie at the Tower of London, that included apes, leopards, lions, even a polar bear that was let loose (on a long chain) to hunt fish in the Thames. Many wealthy people kept private menageries, or strange pets.

George Stubbs

1773

Wikicommons

William Wilberforce, the abolitionist politician, had a domesticated menagerie of foxes and hares and hedgehogs that roamed about his house. In 1824, Wilberforce founded the first animal welfare society in the world. The Duke of Richmond kept a famous collection of animals that people traveled far and wide to view. He had everything from lions and tigers to bears (too many bears!) and even a moose. One of my favorite stories about his collection is when he tried to acquire a sloth, but ended up with yet another bear (this reminds me of the people in China who keep ending up with bear cubs with they try to buy Tibetan Mastiffs).

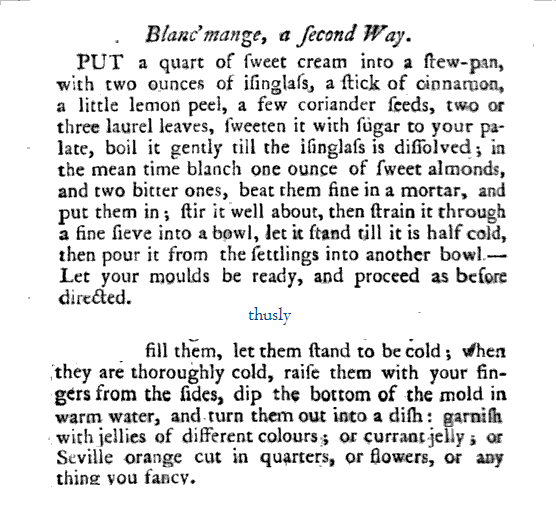

Sr

I received your letter I am obliged to you

for it. I wish indeed it had been the sloath that

had been sent me, for that is the most curious

animal I know; butt this is nothing butt a

comon young black bear, which I do not know what

to do with, for I have five of them already. so pray

when you write to him, I beg you would tell

him not to send me any Bears, Eagles, Leopards,

or Tygers, for I am overstock’d with them already.

I am Dear Sir,

Your Faithfull

humble servant

Richmond.

Another pet that is dear to my heart, and that I may have to someday make use of, is Gilbert White’s tortoise, Timothy. Timothy had originally belonged to Gilbert’s Aunt Snooke. White inherited the tortoise from his aunt in 1780 and it lived with him for the rest of White’s life (Timothy outlived White as well as the aunt). Timothy was reportedly a great favorite in the village and during the summer months would range all over White’s five acre garden. Timothy hibernated during the cold English winters (and this clearly didn’t harm him as he lived a good, long life).

There are documented races in London parks between cheetahs and greyhounds. There was an emporium in the London docks that specialized in exotic animals. There was a constant influx of odd animals brought ashore by sailors and brought home by travelers. Everything from elephants to giraffes to dodo birds. To date, I’ve made do with dogs, but someday I just might have to go with something a little stranger…