I’m currently working on jazzing up my workshop on Georgian Textiles for the Beau Monde’s mini conference at RWA next month. So I thought today I’d share a few fabric resources with you all.

There is an amazing reproduction of one book belonging to a particular woman out there: Barbara Johnson’s Alum of Fashions and Fabrics. Unfortunately, it’s out of print and very expensive these days. But if you Google it, quite a few of the pages are posted on the internet and it’s fairly easy to find in most large library collections. Her book is fascinating as contains not only swatches, but period fashion plates and notations about the gowns made with the fabric.

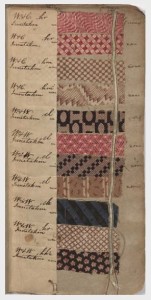

There used to be a couple of great swatch books that were readily available (Textiles for Regency Clothing and Textiles for Colonial Clothing) but both are out of print and shockingly expensive now.

There are also the Threads of Feeling books, which are devoted to scraps of fabric that infants and children left at the Foundling Hospital were wearing (they were meticulously kept as an aid in identifying the child should the parent return to the claim them). This is a great resource if you want to know what people of the lower orders were wearing (there’s an amazing amount of color and pattern to the fabrics; nothing drab about them).

A recent lucky discovery for me is the fully digital collection of swatch and pattern books in the Winterthur Museum’s collection.

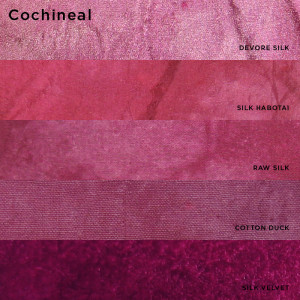

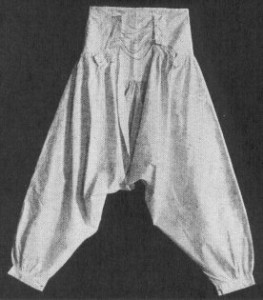

For example this image is from a swatch book dated 1800-1825. The entries indicate the producer and amount on hand, indicating that this was likely an inventory book for a store.

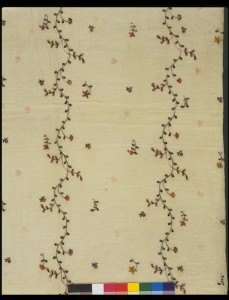

And there are always museum collections. The Victoria and Albert has a large digital collection that features quite a few fabrics (hundreds from the Georgian era alone).

While it’s perfectly fine to simply describe your heroine’s gown as “sprigged muslin”, it can be a bit more fun to occasionally delve further into the history and describe it as a “block printed muslin with meandering floral embroidery”.