So, I missed my July post (sorry). I was in Denver at the 2018 RWA conference. While there, I gave a workshop on inheriting peerages. It was a lot of fun, and people got really into it. They came up with all kinds of crazy situations to ask me about. I wanted to share part of the workshop here, so that those who didn’t make it could still benefit.

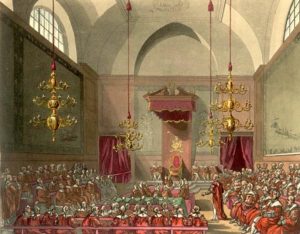

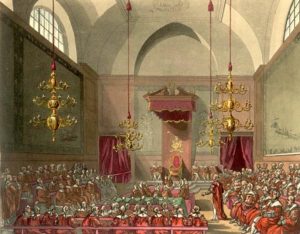

House of Lords, 18th Century WikiCommons

One important thing to understand is that the crown can’t take a title away. That power lies only with Parliament, and Parliament has already stated flat out that once a man is ennobled, this can not be changed except by an act of Parliament. This is called an act of Deprivation. As a matter of public policy it has only been done once (Duke of Bedford 1478; the man was ruled to be too poor to support the dignity, and his state was a result of his having failed to properly care for the lands he’d been given with the title; essentially he was ruled too incompetent to be a duke). The only real reasons for Deprivation seems to have been a peer being convicted of treason (even a murder conviction, as in the case of the 4th Earl Ferrers, didn’t result in the title being lost; it passed to his younger brother after he was hanged). Debt became a legal reason for such an action under the Bankruptcy Act in 1883, but it would have been very unlikely to have been used in the Georgian/Regency period. If you read the section on Deprivation and the Earl of Waterford (p. 227-230) in the law book I link to in the post you’ll see that in 1832 it was ruled that really what Parliament and the crown were allowed to take away were really only those things that the king could “have and enjoy” and this did not include dignities, but was limited to physical things such as land.

So, that means if there’s going to be a challenge, the story will have to be shifted back in time to the point when the hero was making his petition to the crown. The man who would inherit if the hero were illegitimate (or his guardian if he is a minor) would have to apply to Parliament to present their own claim and in that claim they would have to provide the proof of the first claimant’s illegitimacy.

Now here’s the second sticky wicket: English law was HEAVILY weighted in favor of all children of a marriage (all those produced by the wife) being considered legally legitimate regardless if everyone knew that she had lovers and the kid looked nothing like her husband (see the infamous Harleian Miscellany; there were open doubts about the actual parentage of the countess’s children, but no challenge to their legal legitimacy).

In order for a child to be ruled illegitimate, the father would have had to have literally had NO access to the mother for the entire period surrounding conception (not just a few short weeks, but likely at least 3 months). And by no access, I don’t mean that the husband simply states that he never touched her, he had to have been unable to do so. If there was any chance that he COULD have been the father (and merely having access to her person was considered enough) then he was the father. He might not like it, but there wasn’t anything he could do about it (this is why a wife’s good character was so important).

As if this isn’t enough to get over, once the child was accepted, there was no changing his mind. The father can’t decide when the boy is five, or twenty, or when his elder son dies, when he himself is on his deathbed that he wants to cast off a child that has been legally established as his. Again, this is about maintaining the social order, making sure children are not cast off onto the parish, and ensuring that father’s are responsible for their children. The father’s suspicion or even outright knowledge that he wasn’t the father wasn’t enough to make the child a bastard in the eyes of the law.

So, it’s not enough that the second claimant show that everyone knew and admitted that the hero wasn’t fathered by the duke. The claimant has to show that under the LAW the hero was not a legitimate child of the marriage. This means that either the duke and duchess were not married before his birth (as in the already quoted Berkeley case; side note, if the title is Scottish, even this doesn’t work, as marriage legitimized bastards under Scottish law) or that the duke was absent from his wife for a period of months and could not have sired him (and even this might not be enough if the son was publically claimed by the father and had been treated as the heir, but at least it would be something for the Committee for Privileges to gnaw on).

What this comes down to is that it is likely that all the villain of the piece can hope to do is embarrass the hero (unless you want to shift back in time and make the book about the hero’s attempt to claim the title). It’s also likely that he’ll make further powerful enemies, as there are likely other sitting peers who know full-well they were not sired by their legal father.

I hope this was helpful, and I’m happy to answer any specific questions in the comment section.