This post would probably be more appropriate in mid-July, but as things start to cool down here in the Northeast, my mind turns to ice.

Holkham Hall Ice House

In grand estates of the 18th century and early 19th century ice was harvested and kept in ice houses, especially built for the purpose. Ice houses were usually filled with fresh ice every winter. They were usually situated near a pond or a lake, such as the one still extant at Holkham Hall, Norfolk. Once the lake froze in winter, the gardeners would break the ice and take it by cart to the ice house where it was pounded by mallets into a powder,and then rammed down into the ice house to form a solid mass.A lining of staw was usually put between the wall of the ice house and the ice to insulate it. The entrance lobby was simularly insulated with straw.

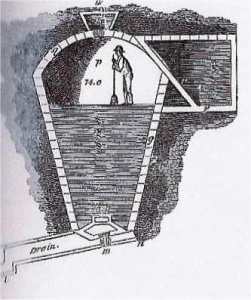

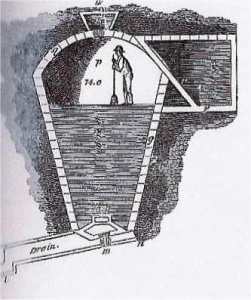

Ice House Section

As you can see from the diagram here, these houses were constructed so that the main part of the storage area was below ground for insulation purposes. The one at Godmersham, home of Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen Knight, was also shaded by tress grown around the entrance mound of the ice house .

Once it was empty of ice in late summer the ice house would have been used as a temporary store for root vegetables. Until around around 1820, ice houses in cool weather were used solely for storing ice. Around that time, it was realized that the ice house could be used as a very simple freezer, and could preserve fruit such as cherries, strawberries, raspberries, and peaches.

A better name for these buildings was an Ice Well- this was the term used in the 1660’s when they were first introduced into England from Italy.

Of note, of course, is that one of the uses for ice from these ice houses was making sorbets and ice creams.

A good book on this subject is Elizabeth David’s Harvest of the Cold Months; A Social History of Ice and Ices .

Here is a recipe for fruit ice cream from Mrs Rundell’s cookery book, A New System of Domestic Cookery, published in 1816. This recipe gives details of the “ice cream maker” in use at the time.

Get a few pounds of ice, break it almost to powder, throw a large handful and a half of salt among it. You must prepare it in a part of the house where as little of the warm air comes as you can possibly contrive.

The ice and salt being in a bucket, put your cream into an ice-pot, and cover it; immerse it in the ice, and draw that round the pot ,so as to touch every possible part.

In a few minutes put a spatula or spoon in, and stir it well, removing the parts that ice round the edge to the centre. If the ice cream, or water, be in a form, shut the bottom close, and move the whole in the ice, as you cannot use a spoon to that without danger of waste. There should be holes in the bucket, to let off the ice as it thaws.

Georgian Ices

Note.When any fluid tends towards cold, the moving of it quickly accelerates the cold; and likewise, when any fluid is tending to heat, stirring it will facilitate its boiling.

Mix the juice of the fruits with as much sugar as will be wanted, before you add cream, which should be of middling richness.

Ivan Day’s wonderful site on historic food, has a great page on Georgian Ices (also the source of the picture above).

We have loved being part of Riskies and hope to be able to stop back from time to time to check in. But life intervenes and we both find ourselves very busy, so are stepping away for now.

We have loved being part of Riskies and hope to be able to stop back from time to time to check in. But life intervenes and we both find ourselves very busy, so are stepping away for now.