Elegant Extracts in Prose title page

In Jane Austen’s Emma, Harriet Smith tells Emma that her beau, tenant farmer Robert Martin is, indeed well-read.

“Oh, yes! that is, no — I do not know — but I believe he has read a good deal — but not what you would think any thing of. He reads the Agricultural Reports and some other books, that lay in one of the window seats — but he reads all them to himself. But sometimes of an evening, before we went to cards, he would read something aloud out of the Elegant Extracts — very entertaining. And I know he had read the Vicar of Wakefield. He never read the Romance of the Forest, nor the Children of the Abbey. He had never heard of such books before I mentioned them, but he is determined to get them now as soon as ever he can.”

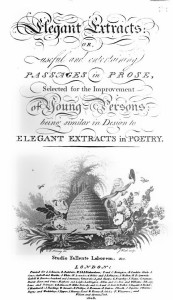

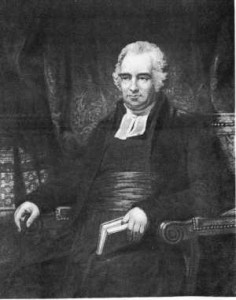

Elegant Extracts in Prose and the companion anthology, Elegant Extacts in Verse, were collated by Vicesimus Knox (1752-1821) who was the Headmaster of Tonbridge School in Kent and was famous for his liberal, enlightened views on education which were influenced by the teachings of John Locke.

Vicesimus Knox

His book Liberal Education (1781) has some interesting points to make about education, and he was particularly scathing about the shortcomings of the state of university education in the late 18th century.

He had attended Oxford from 1771 –1778 and seems to have disapproved of the somewhat immoral regime there. He asserted in his book, that

to send a son to either university without the safeguard of a private tutor would probably “make shipwreck of his learning, his morals, his health and his fortune.”

He suggested reforms to the university system in his pamphlet A Letter to Lord North, which Knox addressed to the Oxford Chancellor in 1789. This pamphlet suggested the intervention of Parliament, and advocated a stricter discipline, a diminution of personal expenses, the strengthening of the collegiate system, an increase in the number of college tutors, the cost to be met by doubling tuition fees and abolishing “useless” professors, with confiscation of their endowments. College tutors were to exercise a parental control over their pupils, and professors not of the “useless” order were to lecture thrice weekly in every term, or resign

Here is an extract from one of his essays: On the Spirit of Despotism (1795):

Ignorance of the grossest kind, ignorance of man’s nature and rights, ignorance of all that tends to make and keep us happy, disgraces and renders wretched more than half the earth, at this moment, in consequence of its subjugation to despotic power. Ignorance, robed in imperial purple, with pride and cruelty by her side, sways an iron sceptre over more than one hemisphere. In the finest and largest regions of this planet which we inhabit, there are no liberal pursuits and professions, no contemplative delights, nothing of that pure, intellectual employment which raises man from the mire of sensuality and sordid care, to a degree of excellence and dignity, which we conceive to be angelic and celestial. Without knowledge or the means of obtaining it, without exercise or excitements, the mind falls into a state of infantile imbecility and dotage; or acquires a low cunning, intent only on selfish and mean pursuits, such as is visible in the more ignoble of the irrational creatures, in foxes, apes, and monkies. Among nations so corrupted, the utmost effort of genius is a court intrigue or a ministerial cabal.”

In all, he sounds rather like the type of teacher of whom George Austen would have approved. Possibly, the Extracts were part of his library at Steventon and were used to prepare Rev. Austen’s pupils for entry to public school. Certainly Jane Austen may have read them herself, or at least knew of the Elegant Extracts in Verse. In her comic poem “I’ve a pain in my head” (written as an account of her visit to Mr Newnham an apothecary with a relation of her brother Edward’s tenants in Chawton), she parodies a poem entitled “The Doctor and the Patient” which is to be found in Knox’s books.

The prose books were collections of essays from publications such as the Rambler, Spectator and the Idler and also contain extracts from works by leading modern authors such as Gilpin , Swift, the Scot Hugh Blair, French philosophers such as Voltaire and classical authors such as Pliny

The books were used a standard texts is schools for years. Indeed, this was the use for which Knox explicitly intended for his books, for he believed in the reading of fiction as a means of exercising the imagination and critical and creative thought.

The books “are calculated for classical schools, and for those in which English only is taught.” The extracts “may be usefully read at the grammar schools, by explaining everything grammatically, historically, metrically and critically, and then giving a portion to be learned by memory” (From the preface of Extracts in Verse).

In 1810 Wordsworth wrote that Elegant Extracts in Verse ‘is circulated everywhere and in fact constitutes at this day the poetical library of our Schools.”

In 1843, Robert Chambers, introducing his own Cyclopaedia of English Literature says it will take the place of Knox’s Extracts which, “after long enjoying popularity as a selection of polite literature for youths between school and college has now sunk out of notice.”

The three volumes of Vicesimus Knox’s anthologies were both expensive and popular: Elegant Extracts in Prose (1783), and Elegant Extracts in Verse (c. 1780) had each at least 15 editions, and Elegant Epistles (1790) had at least 10. Each volume was issued in an abridged form, but in only one or two editions. The unabridged volumes had each about 1000 pages and sold for five guineas. Which was a considerable amount in the late 18th and early 19th century.

So what does this tell us about Robert Martin who reads these books? That he might be better read than Harriet and, quite possibly, Emma. It is so typical of Emma that the girl who can make fine reading lists but never completes her task, is able to dismiss a man who, even though he reads only extracts of works, is probably much better read than herself.

Another point to bear in mind is that he, or at least his family, is prepared to spend quite large amounts of money on books, even though their income would not match Emma’s.

It is interesting that Jane Austen provides a little insight into Robert Martin’s depth of understanding by letting us know that he reads such books as these. It seems to me that she probably approved of this young gentleman, trying to improve himself by extensive reading such books as came his way.