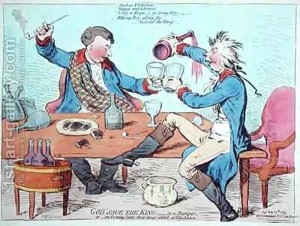

Drinking is in reality an occupation which employs a considerable portion of the time of many people; and to conduct it in the most rational and agreeable manner is one of the great arts of living. — James Boswell Journals 1775

As I just returned from the New Jersey Romance Writers annual conference (at which I had the delightful company of Megan, Elena, Gail, and Diane), I thought I’d write about drinking during the Regency. Now, don’t get me wrong, the conference was not a drunken route, but I did have the pleasure of being introduced to (but unfortunately unable to partake of) a variety of mixed drinks that were new to me and sounded totally delightful. As the weekend drew to a close, I started to think about what our counterparts would be imbibing during – say – a weekend in the country.

As I just returned from the New Jersey Romance Writers annual conference (at which I had the delightful company of Megan, Elena, Gail, and Diane), I thought I’d write about drinking during the Regency. Now, don’t get me wrong, the conference was not a drunken route, but I did have the pleasure of being introduced to (but unfortunately unable to partake of) a variety of mixed drinks that were new to me and sounded totally delightful. As the weekend drew to a close, I started to think about what our counterparts would be imbibing during – say – a weekend in the country.

Peter H. Brown curated the “Come Drink the Bowl Dry” exhibit at Fairfax House in York in 1996 and wrote a brief but excellent companion book of the same name. This post will rely heavily on his research.

Although mead (fermented from honey) and ale (from barley) had been available long before our period and spirits were certainly available, the English country house from the late 18th century onward seemed to run on wine. The wine inventory at Fairfax House in the latter part of the 18th century included port, claret, malmsey madeira, burgundy, and sherry, to name a few. During a normal day, the household seemed to consume one bottle of port and three of sherry, apparently not an irregular amount.

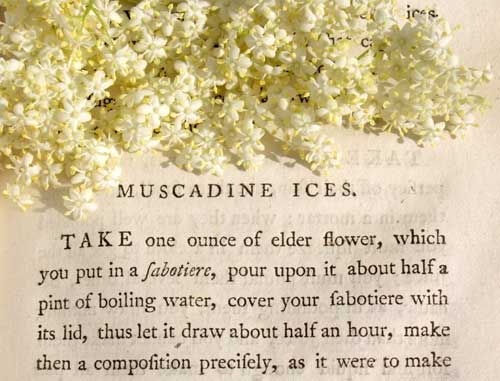

Fairfax House cellar also included beers and ales. Compared to wine and beers, fermented fruit (cider and perry) were considered exotic and were less likely to be found in the cellar of a grand house. Distilled spirits (gin, brandy, arrack, rum) became popular in the 17th century and thence the popularity of the punch bowl. Here are three recipes for you:

Fairfax House cellar also included beers and ales. Compared to wine and beers, fermented fruit (cider and perry) were considered exotic and were less likely to be found in the cellar of a grand house. Distilled spirits (gin, brandy, arrack, rum) became popular in the 17th century and thence the popularity of the punch bowl. Here are three recipes for you:

- One teaspoon of Coxwell’s acid salt of lemons; a quarter of a pound of sugar ,a quarto of boiling water ,half a pint of rum and a quarter of a pint of brandy; add a little lemon peel, if agreeable or a drop or to of essence of lemon. (Note: the boiling water was to enable the butler to dissolve the sugar: it all had to be dissolved before it could be served. — The Footman’s Directory and Butler’s Rememberancer – Thomas Cosnett(1823)

- Three bottles of champagne ;two of Madeira, one of hock ,one of Curacao, one quart of brandy one pint of rum and two bottles of selzter-water, flavoured with four pounds of bloom raisins, Seville oranges, white sugar candy ,and diluted with iced green tea. —“Consuming Passions” by J Green,1984

- In twenty parts of French brandy put in the peels of 30 lemons and 30 oranges pared so thin that the least of the white is left. Infuse twelve hours. Have ready 30 quarts of cold water that has boiled; put to it fifteen pounds of double refined sugar; and when well mixed, pour upon it the brandy and peels adding the juice of the oranges and of 24 lemons; mix well ,then strain through a very fine hair sieve into a clean barrel that has held spirits and put two quarts of new milk. Stir and then bung it to close; let it stand for 6 weeks in a warm cellar; bottle the liquor for use .this liquor will keep many years and improves with age. — Mrs. Rundell, 1816

Mrs. Rundell was apparently expecting a thirsty crowd. Perhaps she was organizing a weekend for romance writers.