Robert Dodsley by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1760. (Image source: Wikimedia.)

Robert Dodsley was popularly known as the footman poet! Wikipedia explains:

In 1729 Dodsley published his first work, Servitude: a Poem written by a Footman…and a collection of short poems, A Muse in Livery, or the Footman’s Miscellany, was published by subscription in 1732, Dodsley’s patrons comprising many persons of high rank.

Dodsley quit his day job in 1735 (with financial help from, among others, Alexander Pope) and from there his career grew rapidly. By the mid-1730s his plays were being produced in Covent Garden and Drury Lane. He was also a publisher and bookseller:

He published many of [Samuel] Johnson’s works, and he suggested and helped to finance Johnson’s Dictionary. Pope also made over to Dodsley his interest in his letters. In 1738 the publication of Paul Whitehead’s Manners was voted scandalous by the House of Lords and led to Dodsley’s imprisonment for a brief period…[I]n 1751 [he] brought out Thomas Gray’s Elegy.

You can read the first edition of Servitude on Google Books, including the foreword exhorting masters to treat their servants better.

There were actually a fair number of working class poets in eighteenth-century England, though their work has been excluded from the canon. A few of my personal favorites are:

1. Mary Collier. Wikipedia notes:

She read Stephen Duck‘s The Thresher’s Labour (1730) and in response to his apparent disdain for labouring-class women, wrote the 246-line poem for which she is mainly remembered, The Woman’s Labour: an Epistle to Mr Stephen Duck. In this piece she catalogues the daily tasks of a working woman, both outside the home and, at the end of the day, within the home as well:

You sup, and go to Bed without delay,

And rest yourselves till the ensuing Day;

While we, alas! but little Sleep can have…

The preface writer (who is identified only by the initials “MB” which don’t belong to anyone on the title page, so not sure what’s up with that) notes, “I think it no Reproach to the Author, whoſe Life is toilſome, and her Wages inconſiderable, to confeſs honeſtly, that the View of her putting a ſmall Sum of Money in her Pocket, as well as the Reader’s Entertainment, had its Share of Influence upon this Publication.” Relatable!

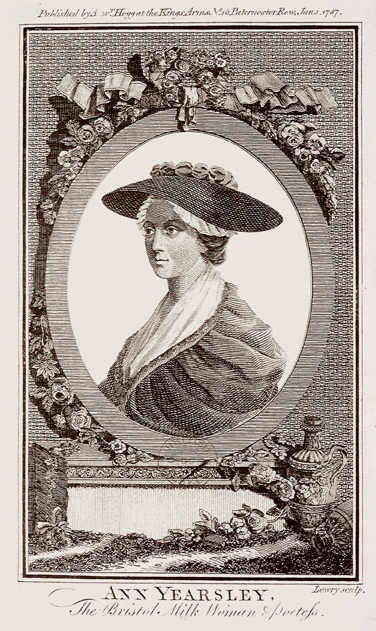

2. Ann Yearsley. I love her! She gave no fucks, refused to go to church, and alienated Hannah More by asking for personal control over the money More had “generously” raised for her.

1787 engraving of Ann Yearsley, via Wikimedia Commons.

I have a biography of her called Lactilla: the Milkwoman of Clifton that is just gripping (I’ve only read the first half because I had to start researching True Pretenses, but one day I’m going to finish it!).

3. Mary Leapor.

4. And of course Robert Burns.

For a more comprehensive survey, check out the Database of English and Irish Labouring-class Poets. It’s a work in progress but the first blog entry, entitled “Static Updates of the Database of Labouring-class Poets,” allows you to download the lengthy list of poets.

Listen to the Moon has no poets, but I’d bet anything my valet hero Toogood has read at least Servitude.