It’s Sandy again. After telling you all about the joys of Rhenish carnival in Germany in my last post, I’d like to take you back to nineteenth-century London, home of many heroes and heroines in historical romance, in today’s post.

We might like to think that our traffic woes — traffic jams, incomprehensible bus routes, or mad drivers – are a product of our modern age, but we couldn’t be more wrong. Traffic, the state of the roads, and, later, public transport caused already the people in the nineteenth century countless woes. Londoners in particular were well acquainted with traffic jams.

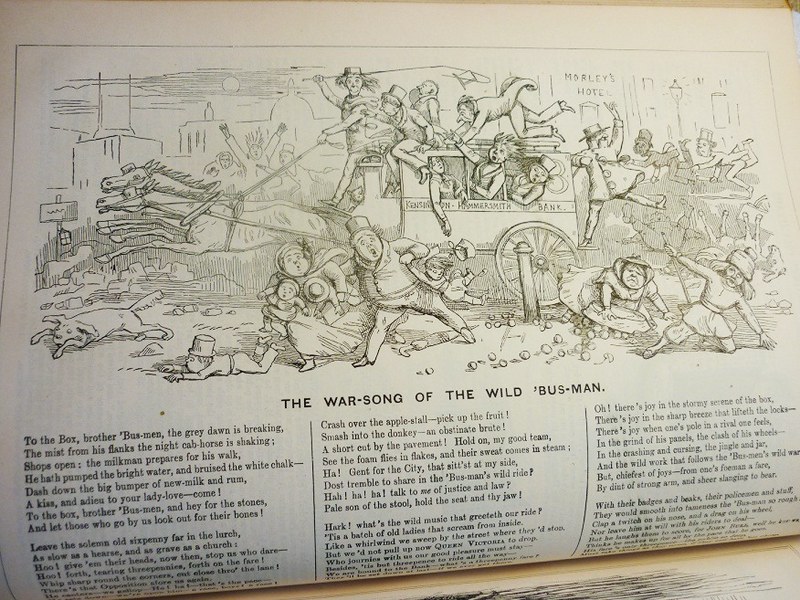

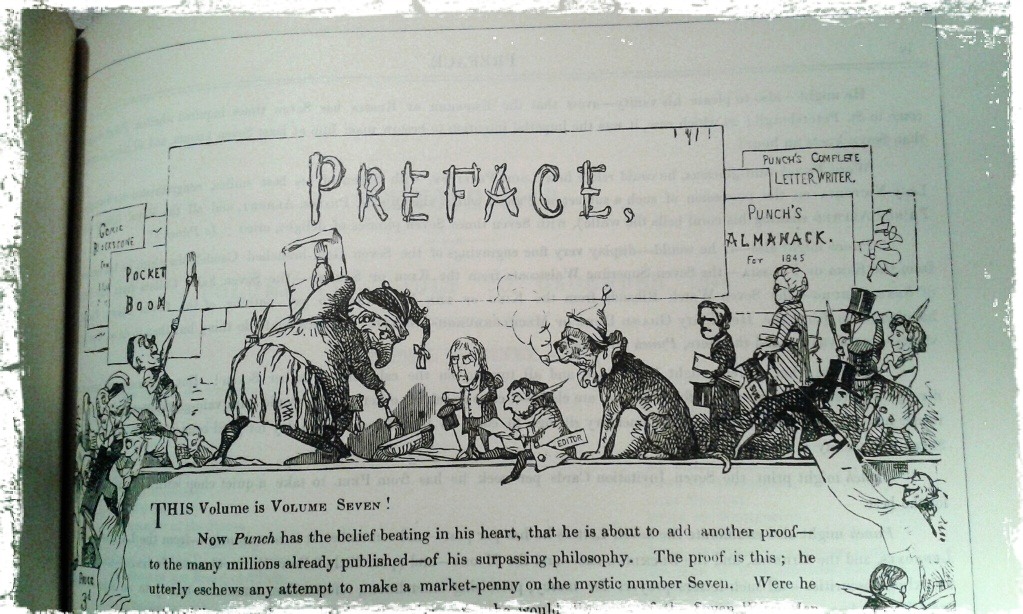

Partly, this problem was caused by the sheer numbers of carriages, carts, and cabs that drove on London’s streets each day and that were joined by countless pedestrians, all kinds of street sellers, and livestock. Add to that some omnibuses, which became a common sight in London from 1829 onwards, when George Shillibeer’s first two horse-drawn buses took up their service. Thanks to Shillibeer’s success, other companies followed and within two decades serval bus services and routes had been established in London. Bus drivers and passengers were the butt of the joke in many Punch cartoons – and many points that the magazine ridiculed are certainly familiar to modern users of public transport. 🙂

The traffic problem in London was not helped by the state of the roads: many of them were unpaved and / or full of holes (the cartoon is again from Punch).

But even as more and more roads became paved in the course of the century, they did not necessarily become easier to navigate. For example, in the 1840s the newspapers were full of reports of accidents caused by the slippery wooden pavement in some parts of the metropolis. The following snippet is from Lloyds Weekly London Newspaper, Sunday, 11 May 1845:

Indeed, accidents on the Strand became so numerous that one month later, in June 1845, it was decided that the wooden pavement between Bedford Street and Charing Cross should be replaced by granite.

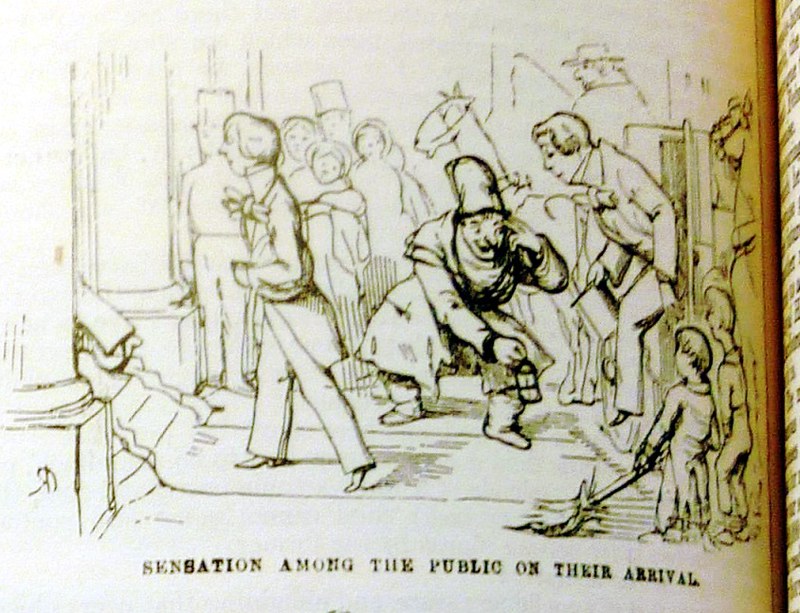

Large society events could also prove disruptive for traffic. Don’t we all love those splendid ball scenes in Regency romances? Ah, but how do our heroes and heroines (not to speak of the countless other guests) get to those balls? They come by carriage, of course. And if 100 or 200 or even more people try to get by carriage to the same place at the same time, you inevitably end up with an interesting traffic situation. In addition, the following cartoon by Richard Doyle (also from Punch) (yes, I do love Mr. Punch *g*) suggests that the arrival of guests for a ball provided a nice spectacle for common people (which couldn’t have helped with the traffic):

And as to the parking situation, London’s inns might have had underground stables, but multi-storey car parks nineteenth-century London did not have – alas. During a ball or other great events carriages were thus often simply left standing in the streets and created major obstructions. For example, in July 1839, when the dress rehearsal for the Eglinton Tournament was held in the garden of the Eyre Arms in St. John’s Wood, about two thousand people (most of them members of the aristocracy and the gentry) came to watch the spectacle. “To give some idea of the number of persons present,” the Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser writes, “it is but necessary to state, that the whole of the adjacent roads and streets, for nearly half a mile round, were lined by carriages three or four deep.” What joy!