I’m a bit late with my post today as I spent the day at the Rhine with friends. And since I’ve already written about 19th-century travels on the Rhine, I thought it might be nice to share pictures of our day trip and add to them some descriptions from guidebooks from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

We visited Koblenz, which Murray’s Handbook for Travellers on the Continent: Northern Germany of 1845 describes thus:

“Coblenz is a strongly fortified town on the left bank of the Rhine, and right of the Mosel. It received from the Romans the name Confluentes, modernised into Coblenz, from its situation at the confluence of these 2 rivers. It is the capital of the Rhenish provinces of Prussia, and its population, together with that of Ehrenbreitstein, including the garrison, is about 25,000.”

Right across the Rhine from Koblenz lies the Ehrenbreitstein. Murray’s tells us the following about the fortress:

“Ehrenbreitstein (honour’s broad stone), the Gibraltar of the Rhine, connected with Coblenz by a bridge of boats. In order to enter it, it is necessary to have permission from the military commandant residing in Coblenz, which a valet-de-place will easily procure, on merely presenting the passport, or a card with the name of the applicant upon it.”

The garrison was destroyed by the French in 1801, but was rebuilt by the Prussians between 1817-1828 and, together with Koblenz on the other side of the river, was meant to protect the Middle Rhine.

One of the most famous sights of Koblenz is the so-called German Corner (Deutsches Eck), where the river Mosel meets the Rhine. After Kaiser Wilhelm’s death in 1888, a colossal equestrian statue was erected here in commemorate the Kaiser who had brought about the German unification of 1871. The statue was finished in 1897.

Bradshaw’s Continental Railway Guide from 1913 has the following to say about other sights of Koblenz:

“The beautiful Rhein Anlagen (gardens and promenade) extends along the river front a little south of the boat bridge. Above and behind the Anlagen is the Schloss [i.e., the Electoral Palace], formerly a favourite residence of the German Imperial family; the royal apartments may be seen.”

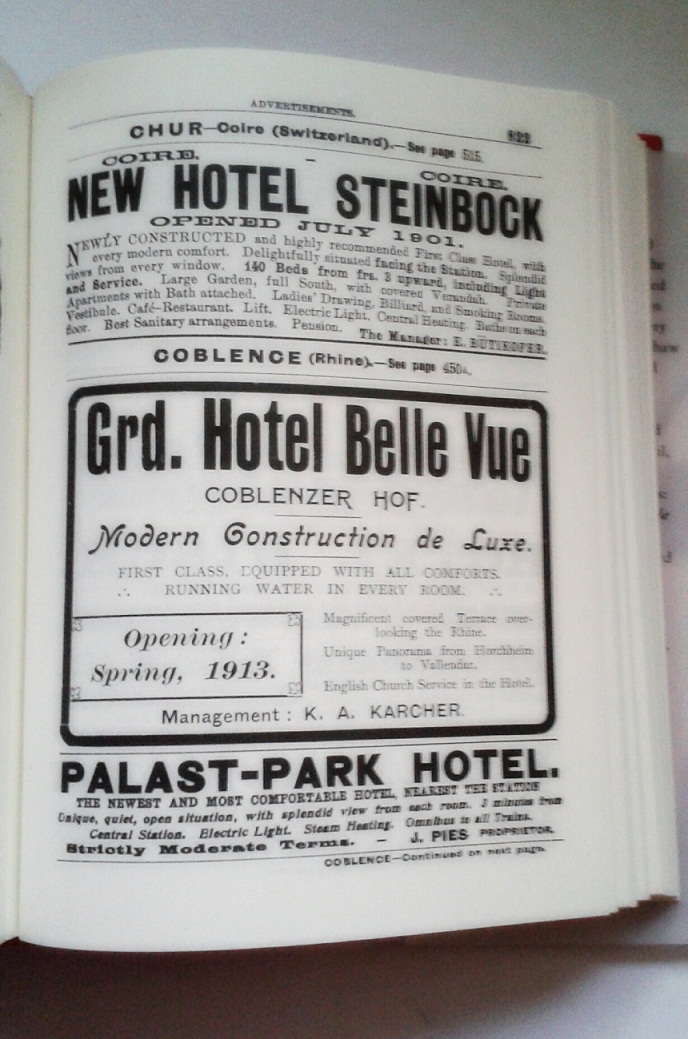

Bradshaw’s also mentions “the imposing Regierungspalast (Government office) with square peaked towers” as well as the “[n]ew first class hotel” right next to it, the Grand Hotel Belle Vue – Coblenzer Hof, which had just opened in spring 1913. The ad in the guidebook proudly points out that there’s “running water in every room.” 🙂

But not just the buildings along the Rhine are particularly nice, you can also find beautiful buildings when you walk through the town itself.

And oodles of churches like the Liebfrauenkirche, which is dedicated to Mary.

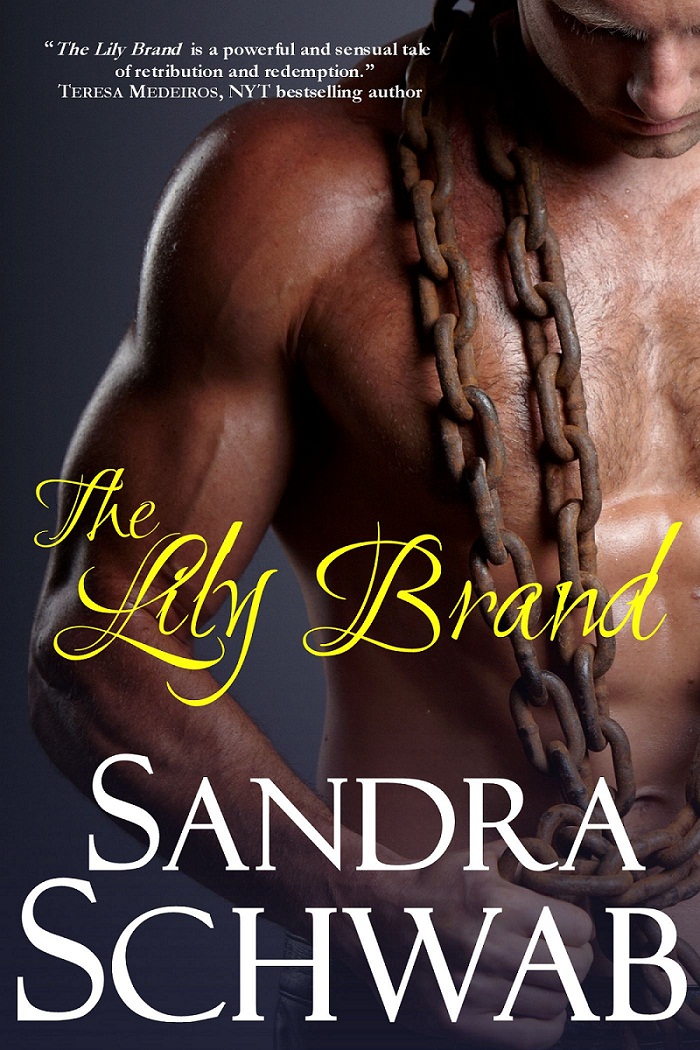

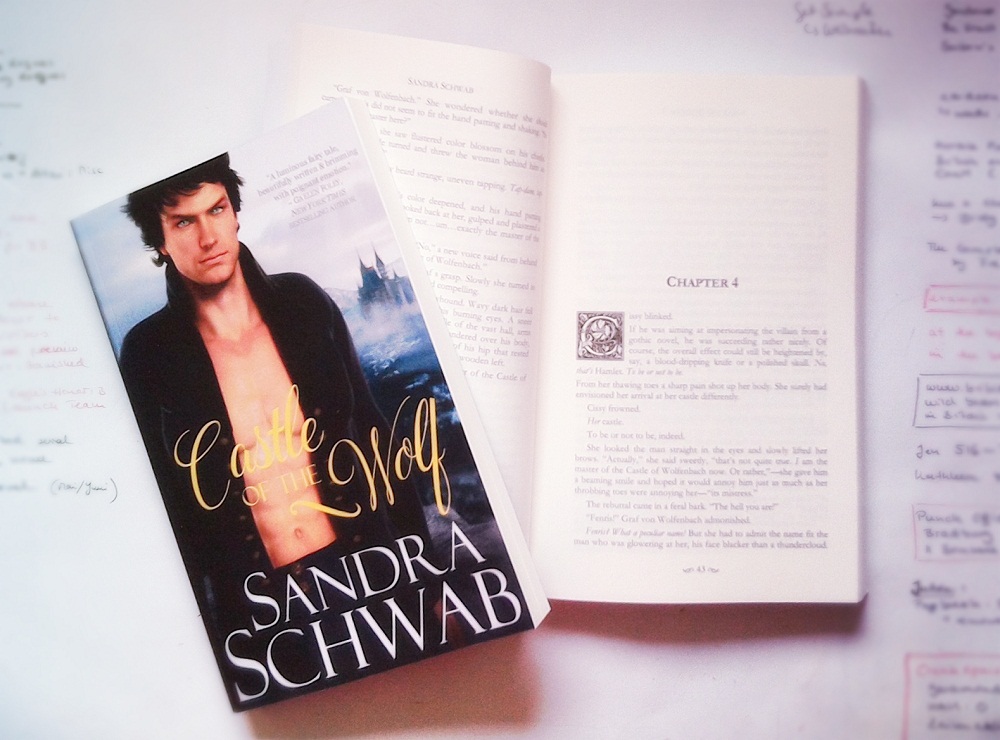

As you can see I had a truly wonderful day! 🙂 And I also had something to celebrate, namely the re-launch of my debut novel, The Lily Brand, which was published ten years ago by Dorchester. Here’s the blurb & the pretty new cover. Until the end of this week, you can still snatch it up for the launch price of $2.99.

Troy Sacheverell, fifth earl of Ravenhurst, was captured in France. He’d gone to fight Napoleon, but what he found was much more sinister. Dragged from prison to an old French manor on the outskirts of civilization, he was purchased by a rich and twisted widow. And more dangerous still was the young woman who claimed him.

Lillian had not chosen to live with Camille, her stepmother, but nobody escaped the Black Widow’s web. And on her nineteenth birthday, Lillian became Camille’s heir. Her gift was a plaything: a man to end her naiveté, a man perfect in all ways but his stolen freedom. Yet even as Lillian did as she was told, marked that beautiful flesh and branded it with the flower of her name, all she desired was escape. In another place, in another world, she’d desired love. Now, looking into burning blue eyes, she knew there was no place to run. No matter if should she flee, no matter where she might go, she and this man were prisoners of passion, inextricably linked by the lily brand.

And while her heart remained locked in ice, his burnt with hate. Would they ever find true happiness?