The heroine in my current work-in-progress, an earl’s daughter, is an athletic, active, outdoors-y sort of young woman but she does have one bit of domestic expertise. After her bookish sister has lectured on the medicinal properties of some spring flowers, Honoria tells the hero, “I do have some skills in the still-room, but I will confess I am more likely to make an essence of violets to flavor biscuits or sugar drops, and to turn the cowslips into wine before I would use them as medicines.” (Yes, her sweet tooth has a role in the story. <g>)

Making wines and distilling flavor essences as well as making medicines were all tasks performed in a large home’s still-room (alternatively “stillroom”, and “still room”). As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, well-to-do Regency people who didn’t wish to purchase expensive perfumes from merchants like Floris might make their own scents in their estate still-rooms as well.

Exactly what was a stillroom?

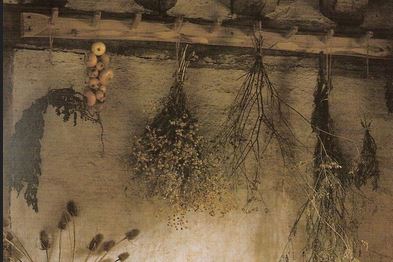

I love this description from Wikipedia: “a working room, part science lab, part infirmary, and part kitchen.” It was always a separate room, really a small “auxiliary kitchen” that provided space for making herbal remedies and other health products, creating essential oils, brewing and distilling beer and wines, making jams and preserving food by fermentation and pickling, among other functions, all out of the way of the business taking place in the main kitchen. It would usually be equipped with its own fireplace/stove, work table, still, shelves and storage cupboards or dresser and racks for hanging dried herbs, etc. Finished products might be moved to a storage room or stored in the stillroom if space allowed.

The name is a shortened form of “distillery room.” According to author Sharon Lathan (whose wonderful article (The Georgian Kitchen) includes a section on the still-room), The History of Hengrave claims “The earliest recorded “still-room” was at Hengrave Hall, Suffolk, in 1603….” Merriam-Webster’s dictionary dates the word (not hyphenated) to 1710. But distillery rooms are ancient. They were not only features in medieval castles (sometimes as a separate structure), but even date back as far as the Romans and Greeks, who had dedicated rooms for creating herbal medicines and distilling essentials oils from plants including roses, lavender, and rosemary.

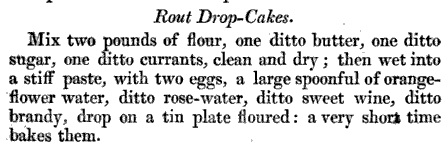

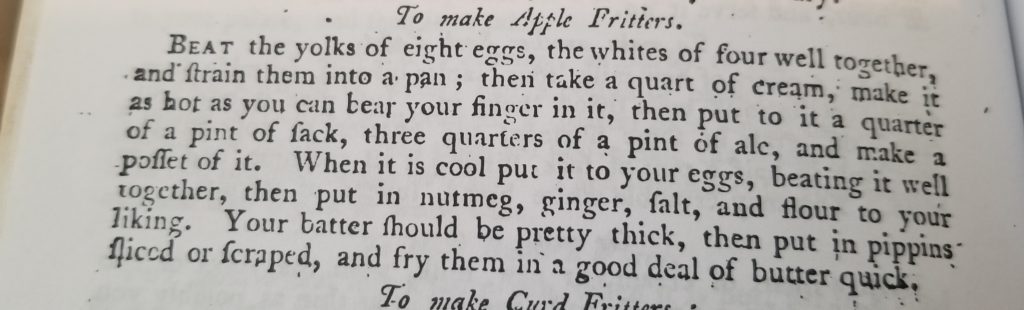

Definitions of the still-room as “a room connected with the kitchen where liqueurs, preserves, and cakes are kept and beverages (such as tea) are prepared” (Merriam-Webster) are referencing the modern role the stillroom took on when its former functions gradually became obsolete. Some 21st century hotels and restaurants still have a “stillroom” used for these later purposes, and lists of equipment and definitions can be confusing because of this fact. But the most basic purpose of the stillroom is intact –it removes these functions and procedures from the busy main kitchen and gives them their own space.

What changed? The commercial availability of items that were at one time made in the still-rooms of estates—medicines, perfumes, cosmetics, cleansers, alcoholic beverages, even the essential oils used in all these things and as flavorings for food. As physicians and apothecaries (even barber shops, as we saw in Part 1) became more numerous and widespread, the need for these items to be made at home diminished, and in many cases, including perfumes, the quality of the commercial products (at least then) was better than could be achieved at home because of the greater access to ingredients. By the mid-19th century (1860’s) references relegate the still-room to the province of the housekeeper or stillroom maid, but also note that “our grandmothers” used to be the ones who presided there –in other words, the lady of the house in the Regency part of the century and earlier.

For centuries, the lady of the manor was responsible for handing down the precious knowledge from previous generations and teaching her daughters the skills to produce the life-saving substances the household and all its dependents (staff, servants, tenants…) needed. Treating illnesses and preserving food were skills that also enhanced a young woman’s value as a marriage partner. Work in the still-room required the ability to read the receipts, keep records and follow precise procedures, so an educated woman was still required even after the responsibility devolved to servants. In the later 19th century, the position of stillroom maid was a possible precursor to one day becoming a housekeeper, a very respected position.

Starting the process…

Let us now picture our young Regency miss in the still-room at her parents’ country estate, with a basket full of flowers she has gathered from the garden or the fields. Perhaps she has a family receipt for a particular scent that her mother and grandmother also enjoy, or perhaps she plans to experiment with such a receipt to try to create a new scent that will be her own.

What will she need?

To begin, she’ll need an “essential oil” that captures a fragrance for the basis of her scent design. More than one if she plans to create a mix. Common flowers, herbs, spices and fruits are her most likely available sources—she wouldn’t have access to the exotic ingredients the commercial perfumers would have, like these:

She’ll need to know which of these ingredients are easier or harder to work with to produce the oils. In our period, there were four ways to extract those: 1) distillation, 2) expression, 3) maceration, and 4) absorption. So, she’ll also need to know which of these methods works best for the substances she’s planning to use.

In Part 3 (May 10), we’ll look at Recipes and Family Skills –how scents were made (including why Lily-of-the-Valley would not be one your heroine could make at home!).

Meanwhile, what stillroom skills have you practiced? Have you ever canned your own produce, made beer or wine, created a tincture, or even distilled an essential oil? There is a movement to go back to home-made perfumes and remedies today, because of all the chemicals now used in commercial products. (Some commercial businesses are also catering to this trend.) I would love to hear about what you’ve done!

P.S. Sharon Lathan’s article (The Georgian Kitchen, linked above and here) has some great photos I’m not sharing here because of copyright concerns. Well worth a look, however! She also includes a great list of items that a stillroom might produce. Since my focus in this series is specifically on scents, I resisted sharing that here. (rabbit hole side tunnel!!)

I also found these on another source that was slanted much later than Regency, but still pre-dates refrigeration and was based on records from various estates: “some products of the Stillroom could be Cherries in Brandy, Strawberries in Madeira, dried Apricots, and pickling anything from onions to cabbage. Spicey chutneys influenced by contact with the Indian sub-continent and Piccallili. In those days there was also the need to pickle eggs, as hens naturally go ‘off lay’ during winter.”

Pickled eggs are not a favorite of mine, but cherries in brandy? Yes, please! Perfumes, soaps and medicines were only part of the magic being practiced in the still-room.