Passive solar heating is a “hot topic” these days (no pun intended). Did you know it was being used on Regency estates and even 150 years before the period? (Rabbit hole warning!!)

I asked my fellow members in the Regency Fiction Writers about the availability of citrus fruit in remote Derbyshire in April 1814. I asked because many of the Regency recipes I have seen require oranges or lemons as part of the ingredients, and the characters in my current wip, Her Perfect Gentleman, needed some for a project. These fruits grow best in places like Spain, Italy, the Caribbean or Florida, and I wondered how much the Napoleonic Wars disrupted these imports.

An interesting discussion followed and uncovered some wonderful sources. The answer was: not as much as you might think, because the trade was so important and the Royal Navy made sure to protect the shipping trade routes. But I still wondered how far north the distribution of imported fruit would reach, and how far from the main cities and towns. I was reminded that some of the very wealthy might have orangeries on their estates, and their surplus would be sold. But how common were orangeries, and how far north could they still be effective?

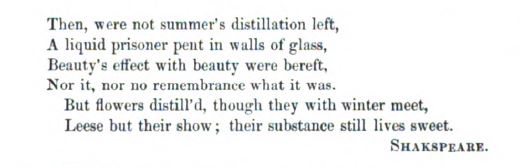

The earliest orangeries began as shelters created to protect fruit trees being grown against south facing “fruit walls” in gardens. The use of fruit walls in northern Europe to create a micro-climate for growing fruit dates to the mid-16th century, not coincidentally about the same time as the start of the so-called “Little Ice Age” (c. 1550-1850). A Swiss botanist named Conrad Gessner observed in 1561 how well the sun-heated warmth of a thick south-facing wall improved the ripening of figs and currants. Such a wall, built of brick or stone, both absorbs heat and reflects sunlight during the day and releases heat during the night, which in cold seasons could protect against frost.

Intrepid fruit growers experimented to improve the effectiveness of fruit walls, adding canopies of thatch (or glass, later on) or woven mats or canvas curtains that could be drawn over the fruit trees to protect them from rain, hail or bird droppings, for instance. When techniques to create panes of clear glass came out of Italy, growers began to make cold-frames to start seedlings early and also to tilt frames with panes of glass against the fruit walls to increase the solar heating effect, protect the trees from winds or other weather and extend the growing season.

The Dutch were particularly adept at innovations in improving the solar growing techniques and were the first to build actual framed glass enclosures along the fruit walls, creating the first “orangeries.” They also began to add other heat sources to supplement the sun, including small stoves inside the enclosures, for example. They also were the first to try building channels within the fruit walls themselves for artificial heat to supplement the sun, developing what became known as a “hot wall” (not to be confused with certain portions of the fortifications at Portsmouth harbour which also bear this label!).

From this common point, the further development of orangeries and hot walls diverges. The French, who discovered improved yields by training their fruit trees or vines along their fruit walls in the method known as “espalier,” also had entire towns adopt fruit walls as an industry. But their walls produced mostly peaches or grapes, not citrus.

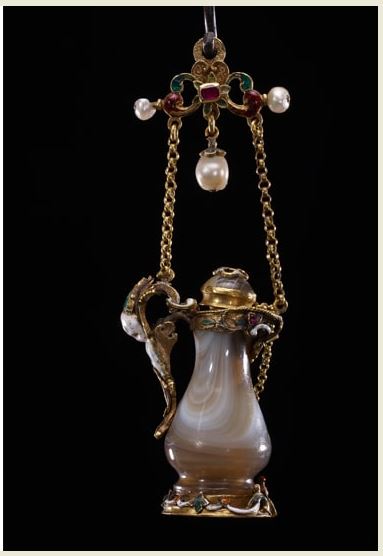

Orangeries, meanwhile, began to be built as separate facilities, designed by landscapers and architects not only to shelter citrus fruit trees but also as places for entertainment, a way to show off a luxury only the very wealthy could afford. Walkways, statuary, fountains, even grottos were added features among the citrus trees, although the buildings needed to be long and narrow to allow light from the windows to reach all the way into the space. The buildings were often designed to echo the architectural style of the main house. As interest in exotic plants grew, the function of orangeries’ micro-climate expanded to offer shelter and display for such other choice and tender specimens.

Some early examples still exist: the orangery at Kensington Palace designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor was built for Queen Anne in 1704 and featured a heated floor. The orangery built at Versailles in the 1680’s was the largest in Europe, designed to hold Louis XIV’s 3,000 orange trees.

Dyrham Park in Gloucestershire has one designed to hide the view of the servants’ quarters from the main house. Built in 1701, it had, like all orangeries at this early period, a solid roof. Humphrey Repton is credited with replacing the slate roof with a glazed one in 1801, about when the technology to do so first began to be feasible.

The Kew Gardens orangery was designed by Sir William Chambers in 1761. At the time, it was the largest in England, but it wasn’t very successful because of low light levels. Its orange trees were removed to the Kensington Palace orangery in 1841 and renovations were made to the building at Kew. Orangeries can be found at more than a dozen estates managed by the National Trust, and many are now used as cafes or restaurants, their many windows and bright light still providing very pleasant surroundings.

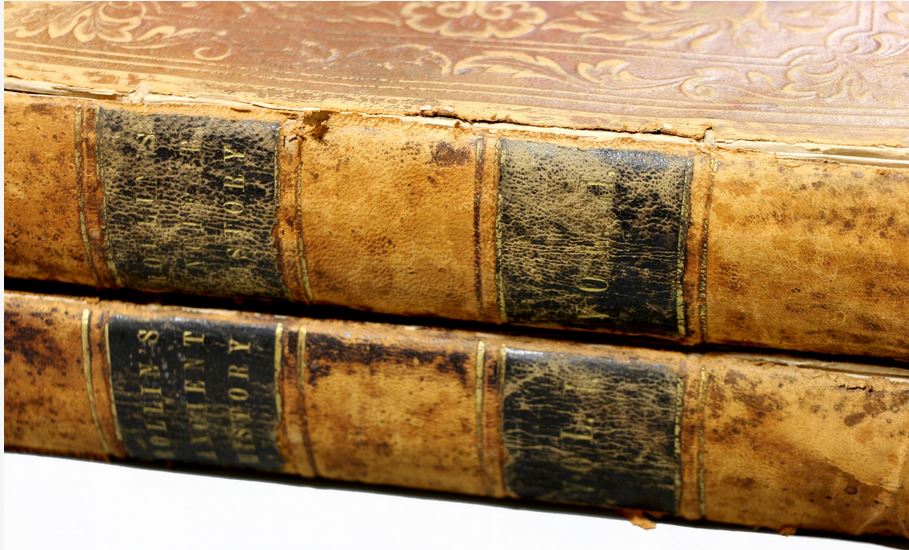

Many private estates that chose not to build an orangery boasted a fruit wall as part of their gardens, however. In England, the added expense of building these in the form of “hot walls’ was often worthwhile because of the colder climate, especially in northern counties. The earliest hot walls were heated by fires actually lit inside the flues, in addition to the sun. Later, the supplemental heat came from small furnaces located at intervals along the back (north) sides of the walls. They were common enough to be described in detail in Phillip Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary in 1754.

The science of creating a successful hot wall is quite impressive, requiring different thicknesses of bricks or stone for various parts of the structure, support for the channels that run through the structure, plastering of the interior heat channels to facilitate cleaning them, and stove chimneys built at regular intervals as part of regulating the heat. Some wall chimneys were fitted with ornamental chimney pots made of Coadestone. Specially skilled masons as well as the expensive custom-made materials were required to construct them. However, none of this provided enough warm shelter to grow citrus successfully in mid-to-northern England without fully enclosing the space. From extant accounts, it appears that the fruits most commonly grown on fruit walls were peaches, nectarines, and Morrell cherries.

How many estates had hot walls is not known. Fruit walls were a labor intensive, high maintenance undertaking, and hot walls added a second layer of labor to maintain and clean the heating system itself as well as to monitor and regulate the heat. The need for hot walls declined as railroads came along, for improved transportation made importing fruit cheaper. Many of the walls were left derelict and were later torn down.

The article on JSTOR cited at the end of this post lists specific estates where hot walls have been recorded: Yorkshire (17), Cheshire (5), Lancashire, (1), and Essex (1). Probably half a dozen more are mentioned in the text also, including Staffordshire (1), Norfolk (1). Wikipedia mentions the one at Croome Court, Worcestershire, as well as two in Scotland in its article on walled gardens. Recent interest has sparked some research and increased awareness that may contribute to more “remains” of old hot walls being recognized and recorded as time goes on.

Improved technologies in the 19th century led to changes in the orangeries rather than their demise—no doubt why more remain to be seen today. But as orangeries became “greenhouses” with more and more glass, they became less and less energy efficient. They lost the balance between heat absorbing, insulating materials like brick and stone to offset the sunlight-providing glass and relied more and more on artificial heating, especially piped hot water. Today, the newest trend in greenhouse agriculture is heading back towards using solar power for both heating and regulating light.

If you’d like to learn more about these early growing technologies, I recommend the following articles:

https://www.orangeries-uk.co.uk/famous-orangeries-in-britain.html

https://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2015/12/fruit-walls-urban-farming.html

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1586918?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

(Hot Walls: An Investigation of Their Construction in Some Northern Kitchen Gardens by Elisabeth Hall)

Or simply see Wikipedia (see “Orangery” and/or “Walled Garden”) for an overview on these!