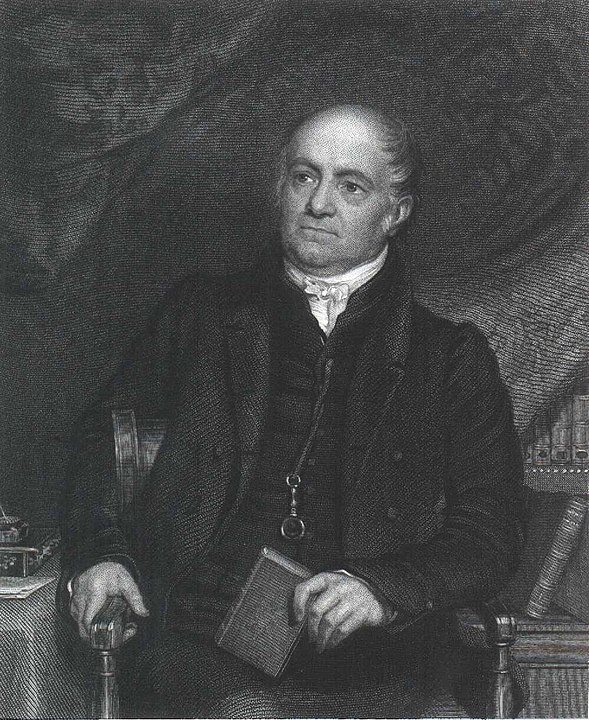

Just in time for “National Pi Day” on 3/14* (not National “Pie” Day—Jan 23), I’d like to introduce to you one the Regency era’s finest mathematical minds, Dr. Olinthus Gilbert Gregory. I fell in love with him first just for his name, I must confess! But he turned out to be a fascinating fellow—well, at least to me! Read on to see if you agree or not.

Part of my fascination, I admit, comes from the missing bits in his story that are links in his path to success. Someone ought to put together a proper biography of the man! Olinthus Gregory rose to prominence from humble beginnings, not an easy feat in the rigidly structured English society of the Regency. He was born in January of 1774, the son of a shoemaker and his wife, the eldest of four children, in Yaxley, Huntingdonshire (now Cambridgeshire). I find nothing more about his early life other than the names of his siblings who were all sisters, and the fact that one (Sophia) died in 1783, when Olinthus was nine. I would love to know where his parents came up with the name Olinthus for their son!! Did a simple shoemaker and his wife have any knowledge of Olynthus, the son of Heracles, or the ancient Greek town that bears this name? The misspelling suggests they might merely have heard it somewhere and liked the sound.

18th century Yaxley must have had a school, or else Gregory was tutored, but either way he must have shown an aptitude for serious study since he was sent to study in Leicester for ten years with Richard Weston, a botanist, mathematician and writer who ran a boarding school there. That city is about 45 miles by road from Yaxley. Was there a Yaxley schoolmaster who recommended this? How old was Gregory when he left home for this? I could find no dates. One must admire his parents for recognizing (we assume) that he was meant for greater things than simply taking on his father’s trade.

Like Gregory, Richard Weston rose from humble beginnings, starting out as a “thread-hosier” according to Wikipedia, but it seems he moved to London for a time and while there nurtured his interest and knowledge of plant science and made connections through the Society for the Arts. His first written works were published during those years. His published output continued without pause after he moved back to Leicester, which no doubt influenced Gregory’s ambition to write and publish. Gregory’s first work, Lessons, Astronomical and Philosophical, for the Amusement and Instruction of British Youth, was published in 1793, when he was 19 years old, and became a popular text used in schools.

He was still studying with Weston at this point in time. Was it through Weston that Gregory acquired the patron who made his publication possible? According to a biography of Gregory at https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/, Gregory was helped by John Joshua Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort, who was a fellow of the Royal Society and also held high political office at the time. Perhaps more significantly, given the way things worked in that era, the Proby family had been lords of the manor near Yaxley (Elton Hall) since 1617. A local lad rising to prominence may have been easy to bring to the earl’s notice.

Weston encouraged Gregory to submit mathematical problems to be published in The Ladies Diary, an annual magazine devoted to such puzzles. Gregory also wrote a treatise in 1794 on “The Use of the Sliding Rule” that was never published, but it brought him to the attention of a new mentor, Charles Hutton, a professor of mathematics at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich.

Sometime between 1796-98 (sources vary) Gregory moved to Cambridge. He served briefly as the editor of the Cambridge Intelligencer, a radical paper, and set himself up as a teacher of mathematics, the start of his academic career. He also opened a booksellers shop in Cambridge, married Rebecca Marshall in Yaxley in 1798, and pursued his writing. Did Weston, Carysfort, or Hutton encourage or help to make any of these connections?

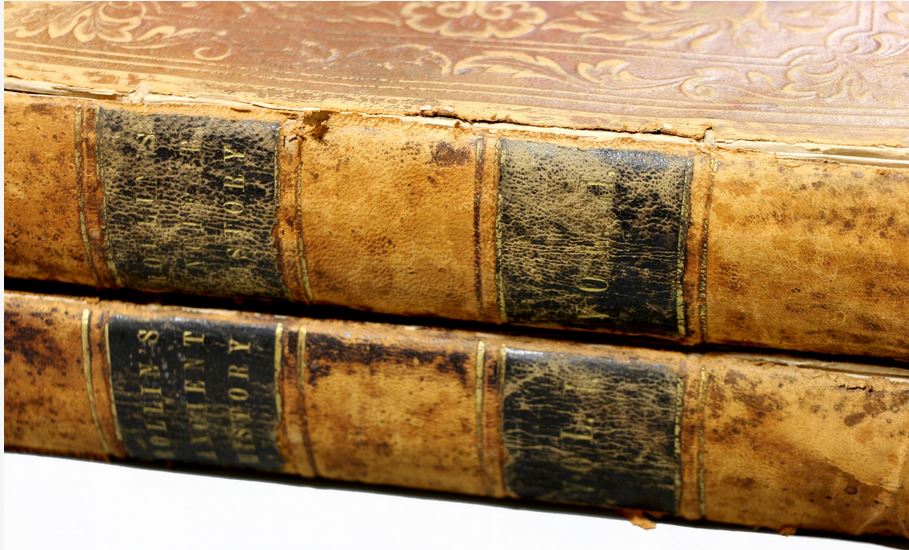

Gregory fathered a son and a daughter with Rebecca. With this family to support, no doubt he was extremely grateful when three things came his way in 1802: 1) Hutton recommended him for an appointment as a mathematical master at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich; 2) he was named editor for The Gentleman’s Diary, and 3) his next major work, A Treatise on Astronomy, was published, dedicated to Hutton. (Like The Ladies Diary, The Gentleman’s Diary was a recreational annual published as a supplement to an almanac and offering mathematical problems and enigmas for readers to solve.)

He received an honorary Masters Degree from the University of Aberdeen in 1806, published the 2-volume work A Treatise of Mechanics, theoretical, practical and descriptive, dedicated to Lord Carysforte, and continued to teach at the RMA as a master until 1807. In that year, his wife died, Hutton retired, and Gregory, at age 33 a widower with two children under age 11, was elevated to the available professorship.

Gregory received a second honorary degree in 1808, that of Doctor of Law, which allowed him to be addressed as doctor. The following year he married his second wife, Anne Beddome, with whom he fathered another daughter and two more sons between 1811-1817. He became the editor of The Ladies Diary in 1819, a position he continued for another 20 years. He also continued as a professor of mathematics and became chair of the academy’s mathematics department in 1821.

While best known for his knowledge and teaching of mathematics, Gregory’s interests were far-ranging, as can be seen by the work on astronomy. Besides mathematical subjects, he also published works on natural philosophy, mechanical physics, and even music and religion—it seems almost anything involving systems interested him.

Nor did he limit his curiosity to the written word. He also performed scientific experiments dealing with astronomy and also sound. The best known of these was carried out at Woolwich to determine the velocity of sound by firing mortars, guns and muskets at various distances from observers. His results (1100 feet per second) have held up well under modern scrutiny with our far more advanced methods of measurement: according to the University of St. Andrews web bio, the speed of sound in dry air at 20° C is 1125 feet per second.

Gregory received many honors for his accomplishments and was co-founder of, most prominently, the Royal Astronomical Society, and also the Woolwich Institution for the Advancement of Literary, Scientific and Technical Knowledge. He was a member of a great many literary and philosophical societies as well and served on boards with other scientific greats of this period, including John Herschel, Charles Babbage, Henry Colebrooke, and Thomas Colby. He remained in his position at Woolwich until he retired in 1838, at which time he was quite ill. He is said to have suffered with illness for the last ten years of his life, but notably he died in 1841, just three years after he retired, at age 67.

In his farewell RMA address in 1838, his devotion to education, and indeed to the very ideals of the Regency period, is abundantly clear, for he tells the first year academy students:

The genuine object of all sound education is the development of the intellectual, the moral, and the bodily faculties of man; or, as it has been sometimes more tersely expressed, the improvement and application of head, heart, and limb. The system of education in the institution in which you have the honour to receive instruction, embraces all this. The blame will be your own, and it will through life be the subject of regret, if any of you quit this Academy without having acquired the manners of a gentleman, the principles of a man of honour and high and pure morality, the ornamental facilities of an artist, and a competent store of literary and philosophical knowledge.

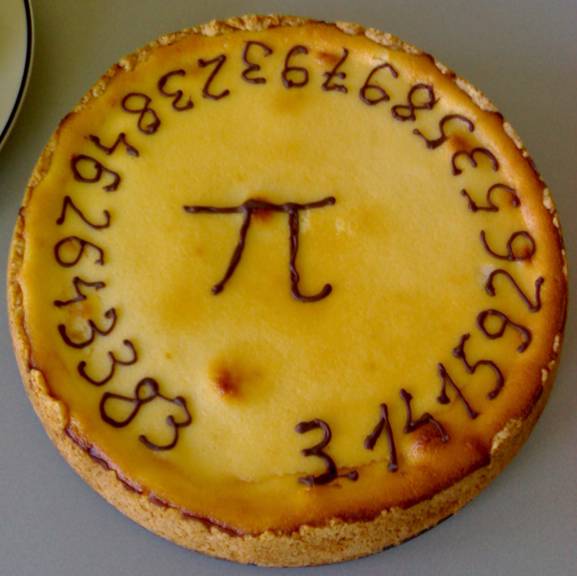

*National Pi Day seems an appropriate time to salute this “real Regency hero” for the success he made of himself and the hundreds if not thousands of young minds he helped to shape. National Pi Day was started in 1988 and is on March 14 each year because 314 are the first three digits in pi.

If you need a review: pi is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, represented by the Greek letter Pi because it is actually an irrational number (a decimal with no end and no repeating pattern). Depending on how far towards infinity you wish to go, the value may be written as 3.141592654…, or shortened to simply 3.14 or the fraction 22 over 7.

Calculations of pi go back 4,000 years and early on were largely based on measurement. It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes who first used an algorithmic approach to calculate pi. But the concept wasn’t called “pi” until 1647, when English mathematician William Oughtred named it in his publication Clavis Mathematicae. He chose this particular Greek letter because it is the first letter of the Greek word “perimetros,” which means “circumference.” But no one has ever solved the perennial puzzle of pi: If pi is the number of diameter lengths that fit around a circle, how can it have no end?