My last “unsung Regency hero” (Dr James Blundell, May 2) was aware that his pursuits could have a huge impact on the future, and indeed, he was right. Today’s hero, a cobbler named John Pounds, also had a great impact on the future, in the area of education, but he seems to have been completely unaware that his efforts were significant beyond the immediate benefit, even when he became famous and famous people came to see what he was doing. I believe his story is celebrated in Britain, but here in the U.S. he is pretty much unknown. Have you ever heard of him?

My last “unsung Regency hero” (Dr James Blundell, May 2) was aware that his pursuits could have a huge impact on the future, and indeed, he was right. Today’s hero, a cobbler named John Pounds, also had a great impact on the future, in the area of education, but he seems to have been completely unaware that his efforts were significant beyond the immediate benefit, even when he became famous and famous people came to see what he was doing. I believe his story is celebrated in Britain, but here in the U.S. he is pretty much unknown. Have you ever heard of him?

Education for the poor was a controversial idea during the Regency years. In my Christmastide Regency story The Lord of Misrule (not finished yet, working on it!!), my heroine’s father, a rather enlightened vicar, belongs to the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor, which was a real organization. Education for the masses had supporters among the aristocracy –most famously the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, although he became active post-Regency. Many in the upper classes, however, still feared the kind of upheavals that had happened in France only decades earlier, and strongly opposed the concept of educating the poor. They felt education would only make the masses dissatisfied with the conditions of life in Britain and could lead to the same kind of tragic horrors that revolution had caused across the channel.

A split existed along religious lines as well: most of the support for poor education came from the non-conformist churches, and the established Anglican Church would not condone cooperation with them.

Against this background of contrasting opinions we find John Pounds, a simple cobbler who had a shop in Portsmouth. Did John Pounds have a stake in this fight? Not directly, but indirectly he definitely did.

Against this background of contrasting opinions we find John Pounds, a simple cobbler who had a shop in Portsmouth. Did John Pounds have a stake in this fight? Not directly, but indirectly he definitely did.

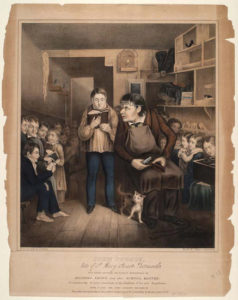

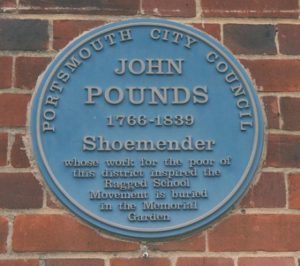

Known in his time as “the Crippled Cobbler of Portsmouth”, John Pounds was born in 1766. In his teen years he was apprenticed as a shipwright at the Portsmouth Dockyard, but just 18 days after the death of his father and just before his 15th birthday, he was crippled by a fall into a dry dock at the shipyard which nearly killed him. After a rather miraculous recovery but unable to continue in that line of work, he learned the cobbler’s trade which sustained him until his death in 1839.

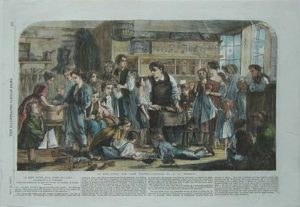

Pounds was apparently simply devoted to the idea of doing good –a humble man improving the lives of the many poor children who roamed the streets of Portsmouth. Armed with warm baked potatoes with which to entice them, he would seek out destitute, often homeless children to invite to his small shop, where he ran a school of sorts and also made certain they were clothed and fed. As he made and repaired boots (no re-soled dancing slippers, as his was not an upper class clientele) he taught these neediest of children, often homeless, to read, write and do sums. He taught them moral values and trained them to live good and productive lives. Sources say that at times he would have as many as 40 children in his shop at once, along with assorted birds, cats and dogs for whom he also cared.

Pounds was apparently simply devoted to the idea of doing good –a humble man improving the lives of the many poor children who roamed the streets of Portsmouth. Armed with warm baked potatoes with which to entice them, he would seek out destitute, often homeless children to invite to his small shop, where he ran a school of sorts and also made certain they were clothed and fed. As he made and repaired boots (no re-soled dancing slippers, as his was not an upper class clientele) he taught these neediest of children, often homeless, to read, write and do sums. He taught them moral values and trained them to live good and productive lives. Sources say that at times he would have as many as 40 children in his shop at once, along with assorted birds, cats and dogs for whom he also cared.

Not surprisingly, his customers took note. Word of his good deeds spread. Supporters tried to give money to help the cause, but the humble yet independent cobbler would only accept donations of clothing or food that directly benefited the children. Famous people including quite probably Charles Dickens (who grew up in Portsmouth) came to see him, and no doubt left inspired by his selfless example.

Pounds did not set out to become the originator of the Victorian concept of “Ragged Schools”, but he has eventually become recognized as such. The prominent Scottish preacher and philanthropist Thomas Guthrie who is often credited as a founder of the movement, himself credited John Pounds as the originator in the 2nd edition of his influential pamphlet “Plea for Ragged Schools” published in 1849, ten years after Pounds’ death.

Pounds did not set out to become the originator of the Victorian concept of “Ragged Schools”, but he has eventually become recognized as such. The prominent Scottish preacher and philanthropist Thomas Guthrie who is often credited as a founder of the movement, himself credited John Pounds as the originator in the 2nd edition of his influential pamphlet “Plea for Ragged Schools” published in 1849, ten years after Pounds’ death.

It is unlikely that John Pounds had ever heard of the London tailor Thomas Cranfield, who started a free day school for poor children near London Bridge in 1798. Another unsung Regency hero, Cranfield established more schools and by his death in 1838, just a year before Pound’s death, had created 19 schools serving London’s poor for free. Certainly his efforts also contributed to the movement toward the Ragged Schools, but his story is less documented, sadly for us.

Pounds never considered what he was doing to be a “school” or ever tried to establish an institution to offer what he did. From all accounts, the personal love and care he lavished on the children that benefitted from his ministry could never be duplicated in a formal setting. Yet it is estimated that over his lifetime the humble cobbler educated more than 500 children.

The most vivid account of John Pounds’ life and achievements is the book written by The Rev. Henry Hawkes, “Recollections of John Pounds”. Hawkes became acquainted with Pounds during the last six years of the old shoe mender’s life and his first person narrative includes descriptions by many other people who were contemporaries and Portsmouth residents. The book has been reprinted in its original form (ISBN: 978-0-9573951-0-7), published by the John Pounds Memorial Church.

Don’t you think one of the fascinating things about history is the parts left out? Do you suppose that grief played a role in John Pound’s fall at the dockyard? He started teaching children about ten years after he opened his shop on St. Mary Street. What do you suppose got him to start when he did? Perhaps a special child who triggered the desire to help? Or a practical need to be established enough in his trade before he could begin to make a difference? He was apparently a devout man who would bring the children to church with him once they were decently clothed. His church helped support his mission –was there an influential minister who helped inspire John? I haven’t read the Hawkes book about him. I wonder if any of these questions are answered in it!!