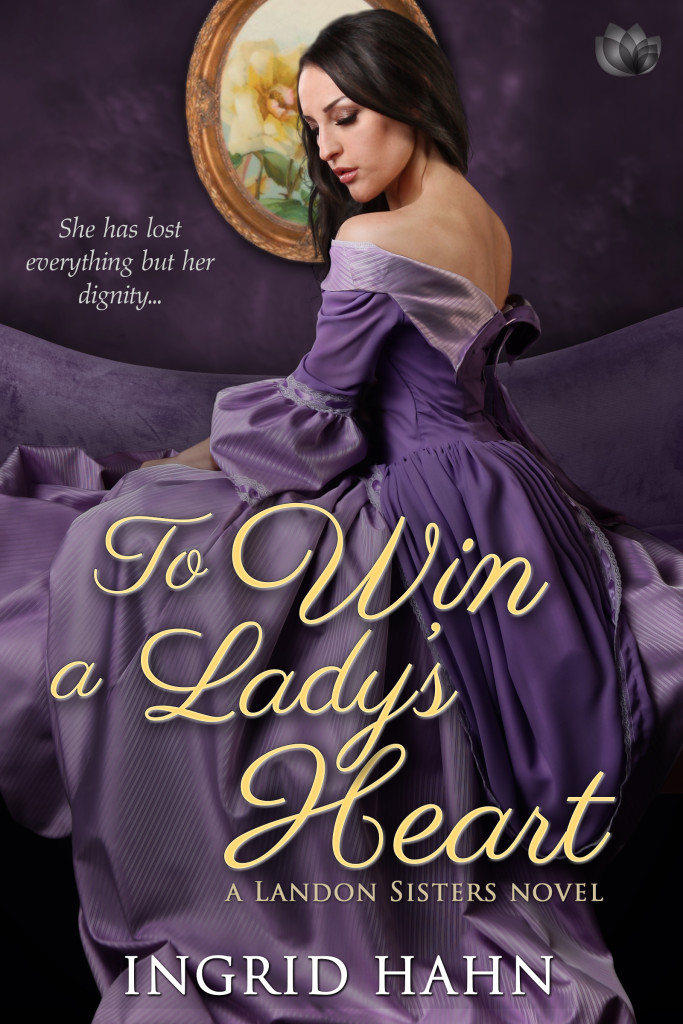

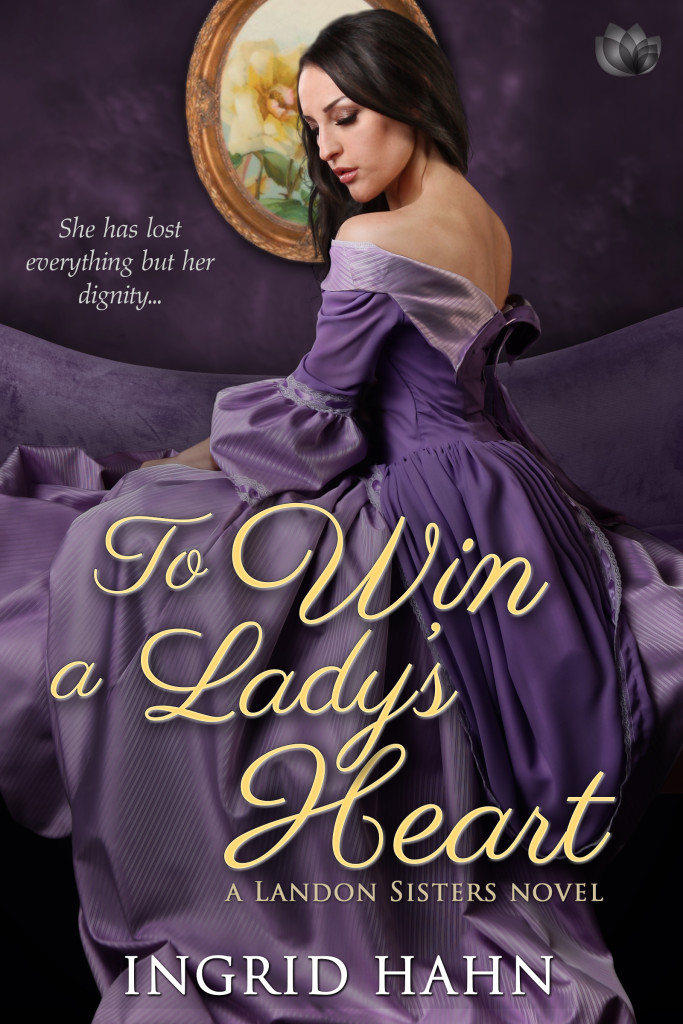

Today I’m very excited to welcome debut author Ingrid Hahn to the Riskies with her book To Win a Lady’s Heart. Welcome, Ingrid and congratulations!

Today I’m very excited to welcome debut author Ingrid Hahn to the Riskies with her book To Win a Lady’s Heart. Welcome, Ingrid and congratulations!

England, 1811. When John Merrick, the Earl of Corbeau, is caught in a locked storeroom with Lady Grace, he has but one choice—marry her.

He cannot bear to tarnish any woman’s reputation, least of all Lady Grace’s.

Lady Grace Landon will do anything to help her mother and sisters, crushed and impoverished by her father’s disgrace. But throwing herself into the arms of her dearest friend’s older brother to trap him in marriage? Never.

Corbeau needs to prove that he loves her, despite her father’s misdeeds. After years of being an object of scorn, not even falling in love with Corbeau alters Lady Grace’s determination to not bring her disrepute upon another. However, if they don’t realize that the greatest honor is love given freely without regard to society’s censure, they stand to lose far more than they ever imagined.

What was the original impulse/inspiration for this book?

An idea had been floating around my mind for some time—a woman going into a storeroom single and coming out again engaged. I started studying tropes and was drawn back to the idea of a forced engagement. But I didn’t know what came next! Not being a plotter was something I used to struggle with, but I decided to embrace it. I decided to start writing to see what happened. So I did. And what happened was much more fun than anything I could have plotted.

Was there any special research you needed to do?

There’s a careful balance with research, isn’t there? “Here is my research, let me show you it” vs not enough period detail to evoke era.

I’m always researching clothing. First, I can’t remember what men’s pants/trousers/breeches were doing in any given year. I look it up, I find something I hope is reliable, I use it, I forget. Regency was a flux time for the lower half of men’s fashions. Sometimes I just pick something and hope it’s not too egregious an error (although I know enough not to use pants, in case you were worried). Yes, obviously we want pants/trousers/breeches OFF our heroes, but sometimes he does have to be around his mother, and she would like them to be ON, thank you very much. Second, I like the names for regency colors. I was pleased to work Pomona into this particular story because green is my favorite color. Browsing at the fashion plates imagining my characters wearing this or that is very fun for me, which is weird, because I’m not really a clothes person.

I also did some research on Regency Christmases. Eventually, though, the Christmas theme took more of a backseat to the rest of the story, so I have a very few light touches here and there, but I pulled back from going into too much detail about the food and other customs.

At the very last minute, I realized I needed to do some research on Regency stables, but between my baby and needing to do a quick turn around after the copy edits, I had to cut part of a line rather than risk another flub.

What’s difficult is sometimes not knowing what you need to research. “Nope,” ended up in this book, which wasn’t used until much later than 1811, but it wasn’t caught until the galley stage (copy editor didn’t catch it, she might not have known either). This is why it’s important to have multiple read your book before delivering to your editor, and at least some of those readers should have some knowledge of your historical time period. Sometimes you just have to accept an error, hope readers will forgive you, and do better next time.

What do you love about the Regency?

I absolutely love the Georgian era. It was a lively time, a lot was being discovered, there were wars here and wars there that add a lot of personal drama and heartbreak in a quickly changing world. The class system was still very much in place (think of Anne Elliot’s objection to Mrs. Clay marrying her father, Sir Walter—and Anne didn’t even very much like her father), so there is a lot to play with between different classes that can help drive up the conflict in a romance novel.

For the regency in particular, I love the fashions—especially earlier, with the gauzy white fabrics, and I love the Grecian hairstyles—and I love the classically inspired interior design. Plus, it doesn’t terrify me. Anything before about 1750 seems dark and incomprehensibly frightening. Everyone seems to have been mad, violent, drunk, filthy, and diseased. The Tudor and Elizabethan eras terrify me. Anything earlier—absolutely not. Nope. No way, no how. I’m a pampered modern woman too used to good dentistry and modern medicine. I like those eras, but I will leave them for other writers to write about so I can keep my cleaned-up fantasy version. Having to do the research myself would put me off them entirely.

What do you hate about the Regency?

Lack of rights for women, lack of equality among people, the idea of having to use a chamber pot (or worse), slavery and conquest in America, war, revolution in France, colonialism in other parts of the world, smallpox, tuberculosis, barbaric childbirth practices (no, please, wash your hands!)…lack modern of dentistry.

Who’s your casting dream team for the movie version?

Oh! Well. Even though physically she’s not as I imagine my heroine, Grace, I would want a young Jennifer Connolly. Nobody can do unassumingly powerful and secretly vulnerable like Jennifer Connolly. She’s probably a little too beautiful to be Grace, not the Grace isn’t beautiful, but we could let that point slide.

Oh! Well. Even though physically she’s not as I imagine my heroine, Grace, I would want a young Jennifer Connolly. Nobody can do unassumingly powerful and secretly vulnerable like Jennifer Connolly. She’s probably a little too beautiful to be Grace, not the Grace isn’t beautiful, but we could let that point slide.

For my hero I’d want a complete unknown. Someone highly trained on the stage who can do incredible acting with minute expression changes and through his eyes. I’d want the glossy magazines to all be crying in outrage: ‘They cast WHO to play John Merrick?’ and ‘Our list of who we would have cast.’ And then for him to become a huge, iconic star always best known for his breakout role in the movie made from my book.

For my hero I’d want a complete unknown. Someone highly trained on the stage who can do incredible acting with minute expression changes and through his eyes. I’d want the glossy magazines to all be crying in outrage: ‘They cast WHO to play John Merrick?’ and ‘Our list of who we would have cast.’ And then for him to become a huge, iconic star always best known for his breakout role in the movie made from my book.

For the Landon Sisters’ mother, Lady Bennington, there is no question. She’s one part Mrs. Bennet, one part —Deanna Troi’s mother in Star Trek: The Next Generation. So she’d definitely have to be played by the (very beautiful) late Majel Barrett.

For the Landon Sisters’ mother, Lady Bennington, there is no question. She’s one part Mrs. Bennet, one part —Deanna Troi’s mother in Star Trek: The Next Generation. So she’d definitely have to be played by the (very beautiful) late Majel Barrett.

What do you like to read?

Everything! Well, not true. Without question, I adore historical romance. But romance is where genre fiction begins and ends for me. I’m not a huge fan of crime, thriller, or mystery. I’m too daunted by the doorstops of fantasy to even try (plus I’m a very slow reader). I dabble in historical fiction, capital-L Literature, a few classics. I’m all about voice. Voice to me is huge. HUGE. Jane Austen, in my book, no pun intended, has the very best voice in English literature—not that I’ve read all of English literature, of course. For period voice, I love Patrick O’Brian, although he wrote much later. I like his characters, too. When I (finally) read All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy, I practically got drunk on the beauty of the language. I followed it up with The Road and was blown away all over again. The story made me cry on the plane, but the language was heaven. I like sharp imagery, reinvented clichés, and having tired, old, everyday things made new and fresh—which makes me the perfect Terry Pratchett fan. Doesn’t hurt that he’s written some of the best characters I’ve ever read, either.

Thought I’m crazy about voice, I’m not really into poetry. I like Mary Oliver, Keats, and Shakespeare, but I find most poetry jarring, inelegant, and trying much, much too hard to be inaccessible. I dabble in poetry in fits and starts, and I have found a few modern poets I like, like Traci Brimhall, and, to some extent, Charles Wright.

What’s next for you?

I am thrilled beyond expression to be working with Entangled again—especially my lovely editor, Erin Molta. My current set of books follow a family, mostly sisters, through the time they fall in love while they’re still grappling with the outfall from their infamous late father’s scandalous downfall. I’m contracted for two more and I have the option of doing the final two if the first three sell well. I’ve had nothing but a wonderful experience with Entangled. I hope my books sell very, very well because I could see myself working with Entangled for quite some time. I’ve had nothing but a 100% positive experience.

Ingrid Hahn is a failed administrative assistant with a B.A. in Art History. Her love of reading has turned her mortgage payment into a book storage fee, which makes her the friend who you never want to ask you for help moving. Though originally from Seattle, she now lives in the metropolitan DC area with her ship-nerd husband, small son, and four opinionated cats.

Ingrid Hahn is a failed administrative assistant with a B.A. in Art History. Her love of reading has turned her mortgage payment into a book storage fee, which makes her the friend who you never want to ask you for help moving. Though originally from Seattle, she now lives in the metropolitan DC area with her ship-nerd husband, small son, and four opinionated cats.

Find Ingrid online at

Facebook

Goodreads

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Interestingly, the tagline for To Win A Lady’s Heart is

She has lost everything but her dignity…

So, you know what I’m going to ask, don’t you. Yes.

Tell us about an undignified episode in your life.

You know, getting locked in a storeroom with an aristocrat and having to eat your way out. If you dare. Or ask Ingrid questions about herself and her book. The winner–and you don’t have to make any embarrassing revelations, although I really, really hope you will, there are other ways, see the rafflecopter options–will receive a free download of To Win A Lady’s Heart. The contest runs through midnight EST on Saturday and I’ll announce the winner on Sunday.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

And here’s a view from the street. Now, there’s an interesting factoid associated with the listing of these houses. Soho in the mid-twentieth century became associated with London’s musical life, (and other things too, such as the sex industry and good restaurants). In the mid 1970s an outbuilding of 6 Denmark Street was used as a recording studio by none other, wait for it, the Sex Pistols. Some of their graffiti still survive. And the buildings have been recognized in a year which coincides with the 40th anniversary of Punk. Yes, Punk is now an institution, recognized by none less than the British government.

And here’s a view from the street. Now, there’s an interesting factoid associated with the listing of these houses. Soho in the mid-twentieth century became associated with London’s musical life, (and other things too, such as the sex industry and good restaurants). In the mid 1970s an outbuilding of 6 Denmark Street was used as a recording studio by none other, wait for it, the Sex Pistols. Some of their graffiti still survive. And the buildings have been recognized in a year which coincides with the 40th anniversary of Punk. Yes, Punk is now an institution, recognized by none less than the British government. Many terrific, literary-themed goodies are here, including some truly gorgeous Alice in Wonderland items such as this cake stand. I have lustful dreams about this cake stand. Thank goodness I don’t bake and thank goodness it’s out of stock.

Many terrific, literary-themed goodies are here, including some truly gorgeous Alice in Wonderland items such as this cake stand. I have lustful dreams about this cake stand. Thank goodness I don’t bake and thank goodness it’s out of stock. Today I’m very excited to welcome debut author Ingrid Hahn to the Riskies with her book To Win a Lady’s Heart. Welcome, Ingrid and congratulations!

Today I’m very excited to welcome debut author Ingrid Hahn to the Riskies with her book To Win a Lady’s Heart. Welcome, Ingrid and congratulations! Oh! Well. Even though physically she’s not as I imagine my heroine, Grace, I would want a young Jennifer Connolly. Nobody can do unassumingly powerful and secretly vulnerable like Jennifer Connolly. She’s probably a little too beautiful to be Grace, not the Grace isn’t beautiful, but we could let that point slide.

Oh! Well. Even though physically she’s not as I imagine my heroine, Grace, I would want a young Jennifer Connolly. Nobody can do unassumingly powerful and secretly vulnerable like Jennifer Connolly. She’s probably a little too beautiful to be Grace, not the Grace isn’t beautiful, but we could let that point slide. For my hero I’d want a complete unknown. Someone highly trained on the stage who can do incredible acting with minute expression changes and through his eyes. I’d want the glossy magazines to all be crying in outrage: ‘They cast WHO to play John Merrick?’ and ‘Our list of who we would have cast.’ And then for him to become a huge, iconic star always best known for his breakout role in the movie made from my book.

For my hero I’d want a complete unknown. Someone highly trained on the stage who can do incredible acting with minute expression changes and through his eyes. I’d want the glossy magazines to all be crying in outrage: ‘They cast WHO to play John Merrick?’ and ‘Our list of who we would have cast.’ And then for him to become a huge, iconic star always best known for his breakout role in the movie made from my book. For the Landon Sisters’ mother, Lady Bennington, there is no question. She’s one part Mrs. Bennet, one part —Deanna Troi’s mother in Star Trek: The Next Generation. So she’d definitely have to be played by the (very beautiful) late Majel Barrett.

For the Landon Sisters’ mother, Lady Bennington, there is no question. She’s one part Mrs. Bennet, one part —Deanna Troi’s mother in Star Trek: The Next Generation. So she’d definitely have to be played by the (very beautiful) late Majel Barrett. Ingrid Hahn is a failed administrative assistant with a B.A. in Art History. Her love of reading has turned her mortgage payment into a book storage fee, which makes her the friend who you never want to ask you for help moving. Though originally from Seattle, she now lives in the metropolitan DC area with her ship-nerd husband, small son, and four opinionated cats.

Ingrid Hahn is a failed administrative assistant with a B.A. in Art History. Her love of reading has turned her mortgage payment into a book storage fee, which makes her the friend who you never want to ask you for help moving. Though originally from Seattle, she now lives in the metropolitan DC area with her ship-nerd husband, small son, and four opinionated cats.