If you assumed that the British holiday of “Mothering Sunday” (this coming Sunday) is the equivalent of the American “Mother’s Day”, only celebrated two months sooner, you’d be making a historical mistake that even lots of Brits make. While it may be mostly true today, that was not always so. Mothering Sunday as observed in Regency times, and centuries before, sprang from both religious and more practical concerns. Did it still have anything to do with honoring mothers? If it didn’t, where does the name come from? Read on, my friends.

If you assumed that the British holiday of “Mothering Sunday” (this coming Sunday) is the equivalent of the American “Mother’s Day”, only celebrated two months sooner, you’d be making a historical mistake that even lots of Brits make. While it may be mostly true today, that was not always so. Mothering Sunday as observed in Regency times, and centuries before, sprang from both religious and more practical concerns. Did it still have anything to do with honoring mothers? If it didn’t, where does the name come from? Read on, my friends.

Mothering Sunday is always celebrated on the fourth Sunday in Lent. That should tell you it’s rooted in Christian tradition, unlike the secular American holiday. Depending on what sources you consult, some claim the early Christians co-opted the Roman celebration in March that honored mothers and the Mother Goddess Cybele, and in its place established Mothering Sunday to be a time of devotion to Mother Mary, the virgin mother of Jesus Christ.

The timing worked well. Early Christians were no dummies, and giving everyone a little break in the middle of the long 40-day fast of Lent no doubt increased the chances that people would stick with the disciplines expected of them. In some places, this mid-Lent Sunday was called “Refreshment Sunday”, or “Sunday of the Five Loaves”.

But as with anything that old, there are multiple roots entwined with these beginnings, and very little documentation. This particular Sunday was also known as Laetare Sunday in the pre-Reformation times. As Christianity and the proliferation of churches spread during the medieval period, the distinction was made between smaller parish churches (known as “daughter” churches) and the major cathedrals in each diocese (the “mother” churches). Important sacraments, such as baptisms, were done at the “mother” churches, presided over by bishops, rather than the local parish priest. On Laetare or Mothering Sunday, families were expected to gather together to make the pilgrimage to their “mother’ church to honor Mary and their own baptisms.

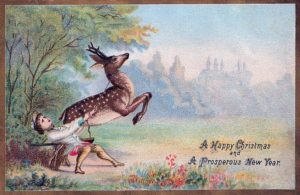

Victorian children bring flowers to church to honor the Virgin Mary.

Since most children were put to work by the age of ten, many lived away from home, serving as apprentices or learning to be domestic servants. A half-day holiday was often not long enough for them to be able to return home, so once a year, on Mothering Sunday, they would be given a full day holiday to visit their families and go to their “mother” churches. That they might pick flowers on the way and perhaps bring small gifts to their mothers is easy enough to believe.

The first known dated written reference to Mothering Sunday is from 1644, when a royal officer from Essex was visiting Worcester and reported that “…all the children and godchildren meet at the head and chief of the family and have a feast.”

Special foods like simnel cake became associated with Mothering Sunday. (In some places it was called Simnel Sunday!) Kind of like the holiday itself, simnel cake is a mixture of things, part fruitcake and part pastry, both boiled like a pudding and baked like a cake. It may have a hard outer crust, and may be coated and decorated with almond paste (11 marzipan balls represent the Apostles minus Judas).  An early reference to it being brought as a gift for “mothering” also dates from the early 17th century. It was usually served with “braggot” (hot spiced ale) or “frumenty” (a spiced drink made from boiled wheat), depending on location.

An early reference to it being brought as a gift for “mothering” also dates from the early 17th century. It was usually served with “braggot” (hot spiced ale) or “frumenty” (a spiced drink made from boiled wheat), depending on location.

After the Reformation, and increasingly up to the Regency period, the emphasis for Mothering Sunday focused far less on the church-going and far more on the day for apprentices and servants to be given time off to visit their families. Imagine how important that day would have been to them, if they could only see their families once a year!

The observation of the holiday declined during the later 19th and early 20th centuries as other kinds of employment became more common. Mothering Sunday had about died out by WWI. But the United States had created Mother’s Day in 1913, and other countries adopted the idea.

Christopher Howse, writing for The Telegraph (2013), says “the revival of Mothering Sunday must be attributed to Constance Smith (1878-1938), and she was inspired in 1913 by reading a newspaper report of Anna Jarvis’s campaign in America. …Under the pen-name C. Penswick Smith she published a booklet The Revival of Mothering Sunday in 1920.” Smith did not want the day to be connected to any one Christian denomination and pushed the revival through secular organizations such as scout groups. Howse adds, ‘“By 1938,’ wrote Cordelia Moyse, the modern historian of the Mothers’ Union, ‘it was claimed that Mothering Sunday was celebrated in every parish in Britain and in every country of the Empire.’” Transformed into a modern holiday! Has it become less meaningful?

Do you live near your parents? How often are you able to visit your family? Do you believe “absence makes the heart grow fonder” or would you stay close if you could? Did you already know this history of Mothering Sunday?