With almost everyone I know preparing for the annual Romance Writers of America conference, my Twitter is full of chatter about clothing, shoes, and makeup. So I thought I’d share a little about Georgian cosmetics (and yes, even when they supposedly went for the “natural look” in the Regency, they were using various concoctions to enhance what nature gave them).

Rouge

From The Art of Beauty: “If ever paint were to be proscribed, I should plead for an exemption in favour of rouge.”

One of my favorite books for this kind of thing is The Lady’s Stratagem by Frances Grimble. She put together information about hygiene, cosmetics, fashion, laundry, and pastimes from six French ladies magazines from the 1820s. I know I’ve heard a lot over the years that women of the Regency didn’t paint themselves the way the ladies of the 18th century did, but I’m not convinced that’s true. I think it more likely they just opted for a more subtle application. The huge number of recipes for cosmetics in the period magazines convinces me that this is true. Ladies weren’t just pinching their cheeks for color, they were painting it on.

True Vegetable Rouge, or Rose in a Cup: Take the kind of red lac extracted from the safflower, which is sold cheaply under the name “rose in a cup.” Dry, it is a greenish-bronze. Dissolve it in a glass of water, and pour it on talcum power of on a piece of fine woolen. In this state it returns to a beautiful rose-colour. You may apply it to your cheeks without withering them, and if you have been careful in preparing the hue, the rouge will not be detected.

Portuguese Rouge: Of Portuguese dishes containing rouge for the face, there are two sorts. One of these is made in Portugal, and is rather scarce; the paint contained in the Portuguese dishes being of a fine pale pink hue, and very beautiful in its application to the face. The other sort is made in London, and is of a dirty, muddy red colour; it passes very well, however, with those who never saw the genuine Portuguese dishes, or who wish to be cheaply beautified.

Spanish Wool: Of this also there are several sorts; but that which is made here in London, by some of the Jews is by far the best. That which comes from Spain is of a very dark red colour, whereas the former gives a bright pale red.

Spanish Papers: They differ in othing from the above [Spanish Wool]; but the red colour, which in the tinges the wool, is here laid on paper; chiefly for the convenience of carrying in a pocket-book.

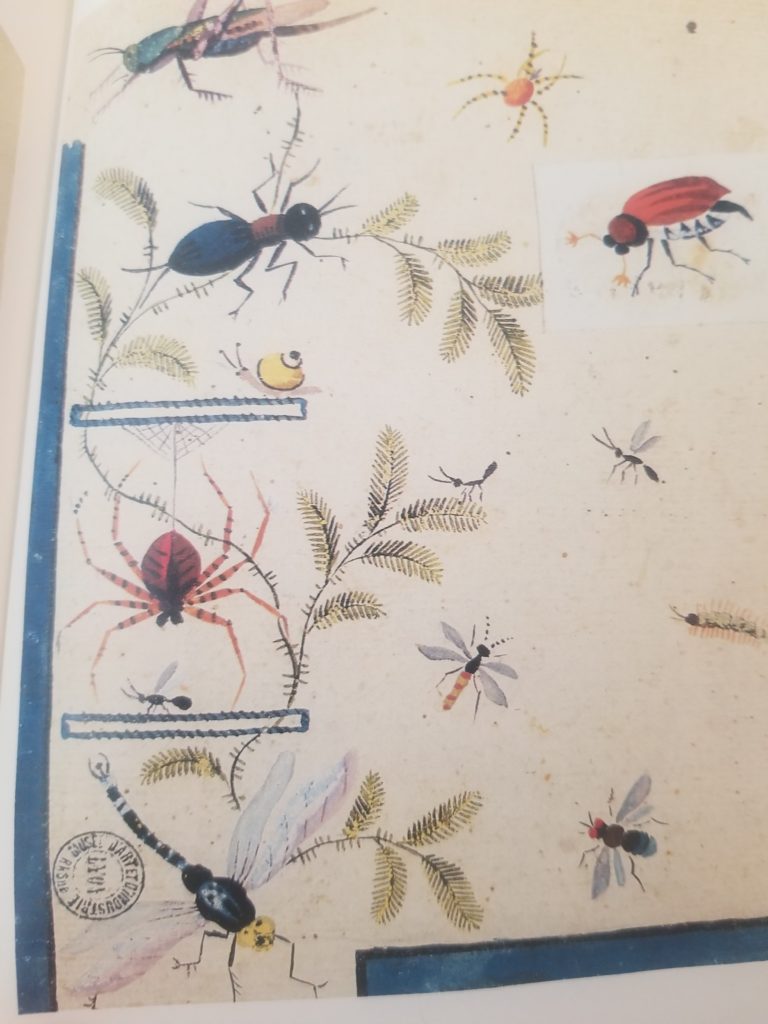

Chinese Boxes of Colours: These boxes, which are beautifully painted and japanned, come from China. They contain each two dozen of papers, and in each paper are three smaller ones, viz., a small black paper for the eyebrows, a paper of the same size of a fine green colour, but which, when just arrived and fresh, makes a very fine red for the face; and lastly a paper containing about half an ounce of white powder (prepared from real pearl) for giving an alabaster colour to some parts of the face and neck.

A further quote concerning the safety of these concoctions: “As to the carmine, the French Red, the genuine Portuguese dishes, the Chinese wool … they are all preparations of cochineal…and the least harm need not be dreaded from its use.”

Eyelashes & Brows

If you look at period Georgian portraits, you don’t see a lot of emphasis on the eyes. Not like today. But there were certainly recipes out there for cosmetics to darken the lashes and brows. The following are from one of the books quoted in The Lady’s Stratagem: To blacken the Eyelashes and Eyebrows. Rub them often with elder-berries. For the same purpose, some make use of burnt cork, or clove burned at the candle. Others employ black frankincense, resin, and mastic; this black it is said, will not come off with perspiration.

Wash for blackening the Eyebrows: First wash with a decoction of [oak] galls. Then rub them with a brush dipped in a solution of green vitriol, and let them dry.

Black for the Eyebrows: Take an ounce of pitch, a like quantity of resin and of frankincense, and half an ounce of mastic. Throw them upon live charcoal, over which lay a plate to receive the smoke. A black shoot will adhere to the plate; with this shoot rub the eyelashes and eyebrows very delicately. This operation, if now and then repeated, will keep them perfectly black.

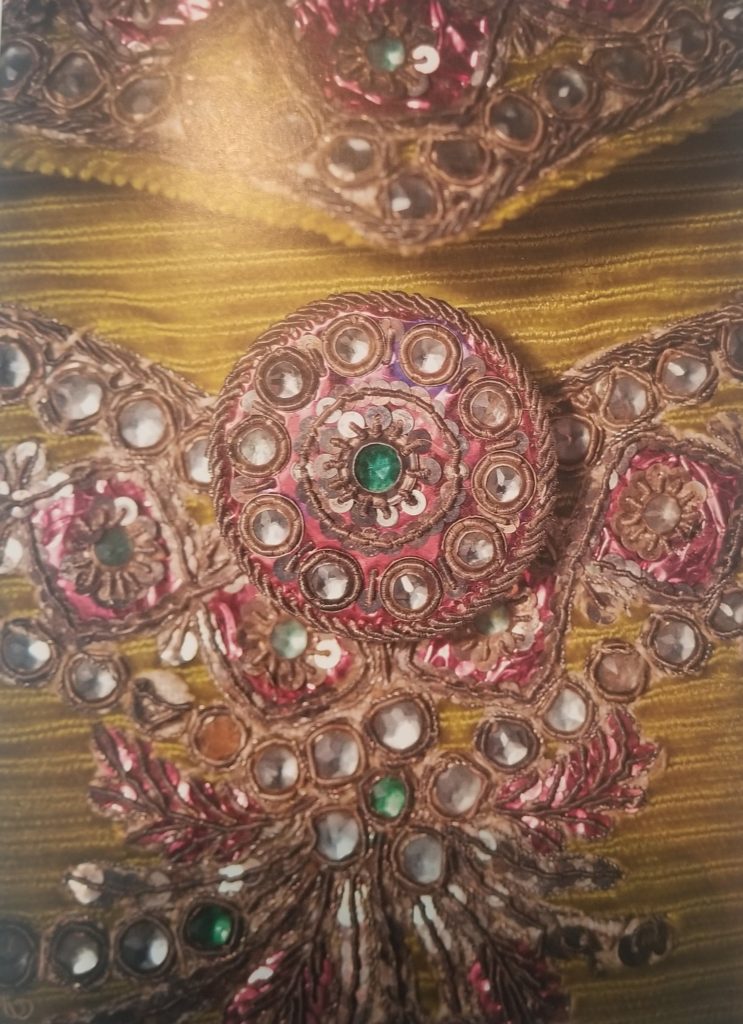

Kohl: Kohl, of course, is ancient. With all the trade the English had with India, there’s no reason to assume that Kohl wouldn’t have been readily available. The OED clearly shows the word was known, though I see it in foreign contexts rather than mentioned as a cosmetic in use among the English.

1799 W. G. Browne Trav. Afr. xxi. 318 If any thing be applied in these flussioni..it is generally kôhhel (calx of tin mixed with sheep’s fat).

1817 T. Moore Lalla Rookh 11, Others mix the Kohol’s jetty die, To give that long, dark languish to the eye.