A few things have happened in the last month or so to put diversity in historical romance at the forefront of my mind. All of them came to a head when I was reading tweets discussing the recent post on SmarthBitches. So I went over and read it. It’s basically the same argument/discussion that I’ve seen kicking around Romancelandia since the oughts when I first joined. I’ve seen it called a chicken and egg syndrome: readers can’t buy what isn’t for sale, but I’m here to tell you, readers don’t seem to buy it when it is for sale. And while we may all bemoan this, that doesn’t change it.

Historical romance is very white, straight, cis, and upper-class. It’s also kind of like playing jenga. It’s really hard to remove one of those and not have the whole thing come crashing down. Why? Let’s take a look (hopefully without making judgments about readers or authors, which I’ve seen quite enough of lately).

Dukes sell. They just do, like it or not. A few authors have managed to make names for themselves by moving into the gentry (Carla Kelley and Rose Lerner spring to mind) and some authors are pulling off love stories among the lower classes (like Erica Monroe), but from what I’ve seen during my writing career, when you leave the ton behind, you lose a lot of the readers who want that extra soupçon of fantasy.

Books set outside of Georgian/Victorian England and Scotland are harder to sell. I honestly don’t know why this is, but even Ireland and France are hard, let alone Ancient Rome or Shogunate Japan. A lot of us thought (hoped!) that indie publishing would unleash a tidal wave of settings that would brush away Regency England’s chokehold on the genre. Didn’t happen. And every time a new historical TV show is a hit, I see a flurry of hope that the setting will crossover into publishing. But it never seems to. Thankfully, there are authors writing other settings (like Beverly Jenkins, Jeannie Lin, and Sandra Schwab), but those are labors of love. Readers vote with their wallets, and the majority of them vote for Georgian/Victorian England and Scotland (preferably with dukes).

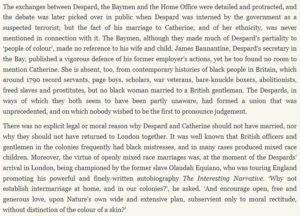

Because the most popular setting is among the 18th and 19th century British ton, the most popular characters are by default Caucasian. There are ways to work in characters of other races/ethnicities (England certainly had free blacks, a Jewish population, Anglo-Indians, Indians, and Chinese), but outside of an Anglo-Indian character, it’s hard to get a non-Caucasian character into the ton. For example, the movie Belle radically changed her actual history to make her wealthy and accepted in a way that she wasn’t in real life. Why? My best guess was that her real life story wasn’t romantic enough. The best examples I can find for how she might have been viewed in her own time are in the works of Austen (Sanditon) and Thackeray (Vanity Fair), which both have wealthy prospective brides who are mixed race as Dido was. Austen treats it as a non-issue. Thackeray does not. Both of which fit with the changing ideas of race and class as depicted in the book White Mughals (which I highly recommend).

Straight and cis. Yep. See above. There are certainly ways to tell gay and trans stories in a historical setting. There are real world examples (Lord Hervey, the Chevalier d’Eon, possibly the Ladies of Llangollen, maybe Dr James Berry), and I’m glad to see these stories being told (e.g. KJ Charles and Cat Sebastian), but we’ve not yet reached a place where these books aren’t niche when it comes to readers (I’ve seen discussions about why some readers avoid these and it’s much the same as why they avoid roms about working class people: the nagging worry about security breaks the fantasy for them; so while a contemp LGBTQ rom works for them, a historical one doesn’t because the HEA never feels “safe”).

So, what does this all add up to? It adds up to authors wanting to make a living (which I’ve been told is an inadequate excuse; a statement with which I strongly disagree) and publishing being a risk-adverse business. When it takes months (or years, depending on the author) to write a book, purposefully writing one that isn’t “to market” is a risky choice, especially if this is how you support yourself. And it comes down to readers.

How does this play out in real life?

When I pitched my first series, c. 2004, I pitched a black hero for book three. I was told by agents and editors that it was a no-go. The profit and loss on it was too risky, especially since those sales numbers would haunt us forever and would probably kill my career (which is funny, since losing a slot at a certain Big Box store killed that pen name long before this book would ever have come out). I did squeeze in a half-Turkish hero (my lowest selling book to date) and I got roundly told that bi-racial characters were “cheating” (as someone who IS bi-racial, this still pisses me off to no end).

[As an aside, I’ve also seen authors’ attempts to diversify their series dismissed as “tokenism”. So I’m damned if I don’t include any diverse protagonist in my series, and damned if I do, but not to the (arbitrary) extent that pleases whomever is deciding these things. Please note, there was a long discussion of this at a recent conference and several authors flat out said they’d rather be dismissed with the faceless majority than paint a target on their back so they could be singled out for tokenism or fake-diversity. I sincerely doubt this is the goal those pushing for diversity wanted, but it’s the one they got.]

Back to me: When I brushed myself off and began pitching again, I always pitched that guy’s book. Agents and editors were suddenly talking about wanting unusual, stand-out books (c. 2008). Books with a different angle. Books with a hook. Books they could promote as DIFFERENT. You know what they meant? They meant maybe not a duke, but still duke-adjacent. Oh, they loved the younger sons angle, but could I throw in a secret society to make it all hang together? I wish I were joking.

Sneak Peak: cropped image of my fencing master’s cover image

Ok, so this time I put that black character IN the series. I was hoping I’d get fan mail asking for his book that I could show my editor. I never did. Not a single email or tweet. What did I get? Requests for very minor (white) walk-on characters. *sigh* When I submitted by my black fencing champion as the hero for one of the books, I got told they’d let me do an e-only novella for him. Not even a novella set with other authors who were also writing Georgian (which they had!). None of that came to fruition anyway, and I left NY, so his book is still sitting there on the back burner (though I have cover shot, so I’ve got that tucked away waiting). This is a story I really want to write, but to date no one has wanted to publish it and I’m honestly not sure readers will pick it up unless I’m very, very lucky. And yes, I have a plan to hopefully help my luck, but if I had to pay my bills with writing monies, I can’t say that this book would ever be written. I know that every hour I put into that book is an hour I might not get paid for; or at least not at the rate that I would get paid if I was writing a duke. But I’m lucky. I have a day job that pays my way and a stubborn streak that wants to write what it wants to write. So, eventually my fencing master will get his book and I’ll get to see if readers love him or if only I do.

So that’s my take. YMMV.