Carlton House

In 1815, Jane Austen was invited by James Stanier Clarke, librarian to the Prince Regent (apparently a fan), to visit Carlton House. One doesn’t say no to the Prince Regent, not to a visit to Carlton House and not to an invitation to dedicate one of her books to him. Jane Austen was not an admirer of Prinny, but she dedicated Emma to him because, what else was she to do?

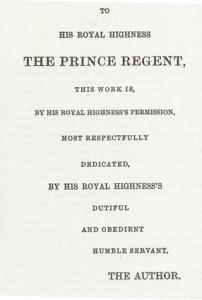

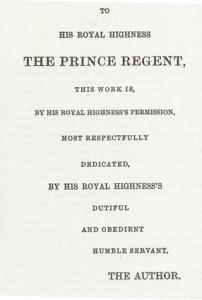

Dedication of Emma

Following her visit to Carlton House, Jane Austen wrote to Mr. Clarke, verifying that the Prince Regent did, indeed want her to dedicate a book to him. What followed was a correspondence between Jane Austen and James Stanier Clarke that I can only imagine she grew to regret.

In answering her letter regarding the dedication, he felt obliged to include the following paragraphs

Accept my best thanks for the pleasure your volumes have given me. In the perusal of them I felt a great inclination to write and say so. And I also, dear Madam, wished to be allowed to ask you to delineate in some future work the habits of life, and character, and enthusiasm of a clergyman, who should pass his time between the metropolis and the country, who should be something like Beattie’s Minstrel —

Silent when glad, affectionate tho’ shy,

And in his looks was most demurely sad;

And now he laughed aloud, yet none knew why.

Neither Goldsmith, nor La Fontaine in his “Tableau de Famille,” have in my mind quite delineated an English clergyman, at least of the present day, fond of and entirely engaged in literature, no man’s enemy but his own. Pray, dear Madam, think of these things.

Apparently, Mr. Clarke could not resist suggesting the theme of her next book, one incidentally based on himself.

Jane Austen excused herself from the task by writing,

I am quite honoured by your thinking me capable of drawing such a clergyman as you gave the sketch of in your note of Nov. 16th. But I assure you I am not. The comic part of the character I might be equal to, but not the good, the enthusiastic, the literary. Such a man’s conversation must at times be on subjects of science and philosophy, of which I know nothing; or at least be occasionally abundant in quotations and allusions which a woman who, like me, knows only her own mother-tongue, and has read little in that, would be totally without the power of giving. A classical education, or at any rate a very extensive acquaintance with English literature, ancient and modern, appears to me quite indispensable for the person who would do any justice to your clergyman; and I think I may boast myself to be, with all possible vanity, the most unlearned and uninformed female who ever dared to be an authoress.

Mr. Clarke was not to be deterred and, having recently been appointed chaplain and private English secretary to Prince Leopold, who was then about to be united to the Princess Charlotte, wrote to suggest, an historical romance illustrative of the august House of Cobourg would just now be very interesting,’ and might very properly be dedicated to Prince Leopold.

Jane Austen once again declined with great civility.

You are very kind in your hints as to the sort of composition which might recommend me at present, and I am fully sensible that an historical romance, founded on the House of Saxe-Cobourg, might be much more to the purpose of profit or popularity than such pictures of domestic life in country villages as I deal in. But I could no more write a romance than an epic poem. I could not sit seriously down to write a serious romance under any other motive than to save my life; and if it were indispensable for me to keep it up and never relax into laughing at myself or at other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first chapter. No, I must keep to my own style and go on in my own way; and though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.

We can only imagine how taxing this barrage of story ideas from a highly placed source must have been for Jane and applaud how kindly she turned them aside. I am particularly amused that she let’s him know that she could “no more write a romance than an epic poet.” I, for one, think she could do probably do whatever she put her mind to.

Some of us have experienced this offering of “ideas for stories.” Should this happen to me, while I never hope to be as clever and articulate as Jane Austen, I do hope to be as polite.

Has this happened to you? How did you respond?