There are many reasons to thank Jane Austen. Hours of escapism reading or watching movie adaptations, hours of pondering or discussing what she was really saying. She’s a great artist whose work is forever open to interpretations–thoughtful, controversial, or just plain wacko–and she will stay with you for a lifetime, changing as you do.

It’s interesting that for a woman whose private life was so very private–thanks in part to Cassandra’s scissors–that she writes so convincingly and with such authority about love.

Her books are about courtship and love, yes, but she deflects her happy endings, leaving her couples on the way to the altar. Her depictions of marriage are not always great–relationships gone stale (the Bennets), marriages that you know are just going to be trouble (the Wickhams). We have the particularly lifeless Gardiners of P&P who are surely there to push the plot forward (sorry, Miss Austen, I’ve always suspected they’re there for that reason). The Crofts are happy but childless, unusual in an age when marriage = children. Is Mrs. Croft’s year ashore, sick and missing her husband, really a reference to a pregnancy that went badly wrong?

Furthermore, there is the evidence in the letters (and sorry, I can’t quote you a reference because then this post would be even later) that falling in love is a woman’s choice; that she can and should allow herself to do so. The implication is that falling in love–an uncontrollable thoughtless impulse–is doomed. (Marianne Dashwood, we’re talking about you.) Love is a power a woman holds in check until the suitable prospect appears, a man of virtue (Edward Bertram, zzzzz), of wealth (Darcy, who is probably not Colin Firth in a wet shirt), or even one who can comfortably provide for you (Mr. Collins. Try not to think about it).

The evidence is in the novels: that not one of her heroines makes a marriage that would in any way defy the social norms. Not even Lizzy and Darcy. Sure, he has a bunch of money and huge tracts o land but she’s gentry, possibly from a family like Austen’s that had some aristocratic connections a few generations ago.His aristocratic connections are too close for comfort.

Check out that first proposal scene again (in the book, not the movie adaptations):

In vain I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.

(Wowsa)

But remember, we’re in Lizzy’s point of view. Austen does not allow us to hear Darcy’s proposal in his words. Instead, we get Lizzy’s interpretation:

… you chose to tell me that you liked me against your will, against your reason, and even against your character?

And that’s what makes Austen so brilliant, by leaving us guessing. And guessing. And talking about it. Her control of point of view, what the reader needs to know and when, if ever, is what I admire most about Austen’s writing.

What do you like most about Austen’s writing? And what do you think is impossible to translate into a movie script?

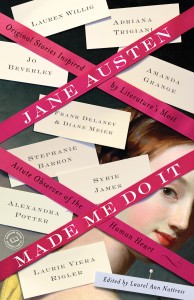

Prizes: Today I’ll give away a couple of copies of Jane Austen Made Me Do It, a collection of short stories edited by Laurel Ann Nattress of Austenprose chosen from among those of you who comment on today’s post. That will automatically enter you into our grand drawing of a $50 amazon gift certificate!

Prizes: Today I’ll give away a couple of copies of Jane Austen Made Me Do It, a collection of short stories edited by Laurel Ann Nattress of Austenprose chosen from among those of you who comment on today’s post. That will automatically enter you into our grand drawing of a $50 amazon gift certificate!

Thanks for joining us to celebrate Austen’s birthday this week.