This weekend I hosted the “Dining for Dollars” Jane Austen Movie Night I’ve been talking about. About twenty people attended and I think all had a lovely time. My goal with the menu was to serve foods based on period recipes that would have a reasonable appeal to modern tastes, but also to make sure to honor the guests’ dietary needs and preferences, including some dishes that were vegetarian, some gluten free, and some nut free. Luckily, no one was vegan, because it’s hard to find recipes that don’t include some butter and/or eggs! I used a lot of recipes from The Jane Austen Cookbook by Maggie Black and Deirdre Le Faye, also some I found online.

The dinner menu:

The dinner menu:

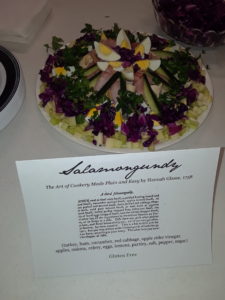

– Salamongondy (pictured: a salad of cold meats, vegetables, and fruit, based on a Hannah Glass recipe)

– White Fricasey (a chicken and mushroom stew, also a Hannah Glasse recipe)

– Roast Potatoes (adapted from Hannah Glasse, using gluten free crumbs)

– Vegetable Pie (adapted from the cookbook of Martha Lloyd)

– Swiss Soup Meagre (also from Martha Lloyd, also adapted to be gluten free)

– Bread, both regular and gluten free (I cheated and bought from a store that has a good bakery)

I served lemonade, burgundy, claret (Bordeaux), and hock (white German wine).

There was a lot to do to prepare, so several friends came early and took the role that would be taken by under-cooks, kitchen maids, and scullery maids, for which I am very grateful!

While the guests were arriving and getting their food, I played Jane’s Hand, a CD of music from Jane Austen’s songbooks. Here is one of my favorites, “I Have a Silent Sorrow Here”, written by none other than Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire and performed by Julianne Baird.

I offered guests a choice of films to watch, and they chose Persuasion, starring Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds, because most had not already seen it. They enjoyed the story and the romantic resolution. Here’s the famous “letter scene”.

Some of my guests were surprised that Persuasion is not as popular as Pride & Prejudice and said they were eager to read the book now.

The dessert menu:

The dessert menu:

– Hedgehogs (adapted from Hannah Glasse–a huge hit but without the calf’s foot jelly!)

– Rout Drop Cakes (little cookies flavored with rose water, sherry, brandy, and orange juice, dotted with currents, a Maria Rundell recipe)

– Chocolate Ice Cream (store bought, gluten free)

It was a lot of work, but so fun I may do it again sometime.

Have you ever done anything like this, or would you like to? Which movies are your favorites? Any foods or drinks you’ve tried to recreate, or want to?

Elena