As promised last month, here is more of our look at Regency summer sports and activities. When the sun shines and the days are warmer, what can’t be done outside? But you might be surprised at which sports were not developed or popular until later than our favorite period. Given the interesting details of the following two games, it looks like we will need to have a part 3 next month to keep this short enough!

LAWN GAMES

Battledore and Shuttlecock

In my almost-finished wip, Her Perfect Gentleman (releasing in November, I hope), a game of battledore and shuttlecock ends a bit disastrously for my heroine, Honoria. What happens is her own fault, for she insists on playing and the ground is still muddy from the previous day’s rain.

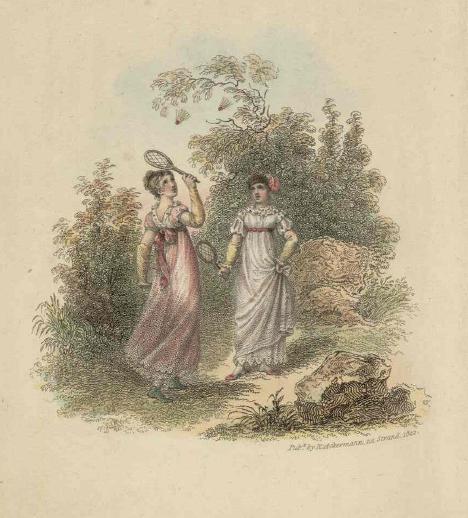

The game (known as Jeu de Volant in France, which means “the game of flight”) has been played in Europe for centuries. Western artworks from the 16th, 17th and 18th century document both adults and children playing it.

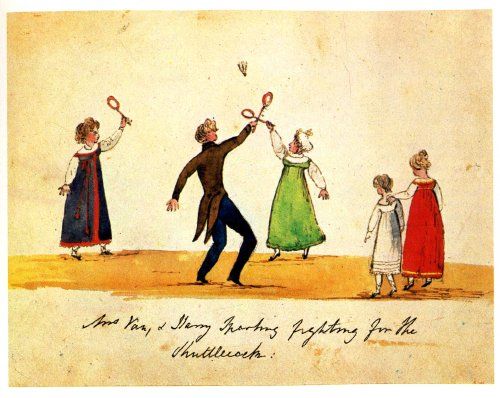

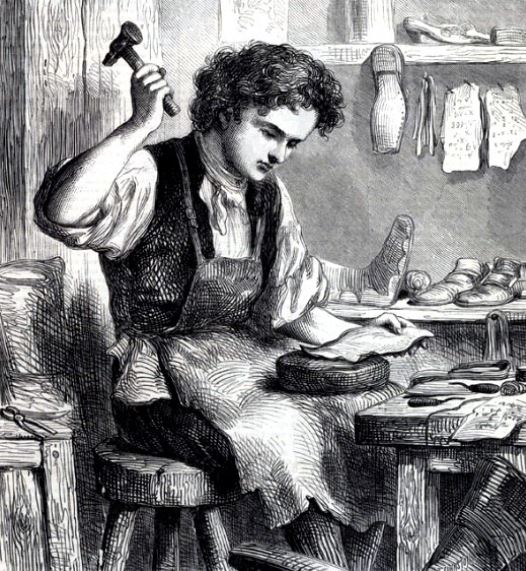

The game differs from our modern sport of badminton, for it is played by individuals without “sides” or a net or defined court space, and the object is to keep the shuttlecock from landing. It can be played indoors (with an adequate space) or outdoors, using battledores (paddles or racquets) usually covered with parchment or gut-string net. The shuttlecock was made from cork (sometimes covered with leather) and feathers.

The British National Badminton Museum says of the earlier game: “If a single player played, they would hit the shuttle in the air counting the number times they could do this without it falling on the floor. Two or more players hit the shuttlecock back and forth. This was usually a cooperative rather than competitive game. The players purposely hit the shuttlecock towards rather than away from each other, their goal was to have as long a rally as possible keeping the shuttlecock up in the air and counting the number of consecutive successful strokes in each rally.”

Indeed, in Diana Sperling’s delightful book Mrs Hurst Dancing we find the following charming (and humorous) entry and illustration:

The Badminton Museum website says: “We know the game of ‘battledore and shuttlecock’ was played at Badminton House as early as 1830 because they still have in their possession two old battledores which have inscriptions handwritten in ink on their parchment faces. The oldest reads: ‘Kept with Lady Somerset on Saturday January 12th 1830 to 2117 with… (unreadable)’.The second says: ‘The Lady Henrietta Somerset in February 1845 kept up with Beth Mitchell 2018.’”

Several sources say the more competitive badminton evolved from Poona, a game with sides and a net learned by the British military in India in the 1860’s. It took on the name badminton in the 1870’s, named after the country estate of the Dukes of Beaufort in Glocestershire where it was either played a great deal or introduced at a party. Other sources suggest that the later version of the game was invented at the estate during a house party in 1860. An article called ‘Life in a Country House’ in the December 1863 Cornhill magazine used the term “badminton” (albeit with an explanation required), so it may have been the first introduction in print of the name in use at the duke’s house. The reference says: “your co-operation will be sought for…badminton (which is battledore and shuttlecock played with sides, across a string suspended some five feet from the ground)….” The North Hall at Badminton House is the same size as a badminton court as we know it today, 13.4m by 6.1m, and five feet is still the standard height for a badminton net. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions on this one!

Lawn bowling (not to be confused with the game of skittles or nine-pin) is so ancient it goes back to the Egyptians 7,000 years ago, and it may have been played in Turkey before that. It is believed that the Roman Legions spread their version of the game (today called Bocce in Italy) to all the European lands, where each country adopted its own variations, influenced by climate and terrain.

Lawn bowling, where the objective is to roll a ball so that it stops as close as possible to a smaller, target ball named the kitty, or jack, was so well established in England by 1299 A.D. that a group of players organized the oldest established bowling club in the world that is still active, the Southhamptom Old Bowling Green Club. The sport was so popular that royalty in both France (where it is called Boules) and England passed laws restricting it for the common people during several centuries, because it had supplanted archery as a pastime and archery skills were essential for the national defense.

In England, Edward III in 1361, Richard II in 1388, and Henry IV in 1409 put restrictions on not only who, but when and for how long certain segments of the population could play. Henry VIII outlawed it entirely for the lower classes in 1541, excepting on Christmas Day, and in 1555 Queen Mary passed her own prohibition on it for the lower classes, on the grounds that it supported “unlawful assemblies, conventiclers, seditions, and conspiracies.” Her restriction on it lasted for 3 centuries!

In the meanwhile, fashionable land owners and the aristocracy could play on private bowling greens, if they paid 100 pounds to the Crown. Samuel Pepys mentions in his diary being invited to “play at bowls with the nobility and gentry.” The cost of maintaining and grooming the greens was prohibitive enough to limit them to the wealthiest circles, such as royalty, or those most devoted to the sport. Many very old bowling greens are still in use today, including one at Windsor Castle, and one at Plymouth Hoe where Sir Francis Drake and his captains were said to be bowling in 1588 when they received the news of the invading Spanish Armada.

Lawn bowling was never restricted in Scotland where rich and poor alike embraced it wholeheartedly and it has remained very popular throughout the centuries. Early versions of the game used a round ball like those used in Boules or Bocce, but later the English version adopted a weighted or “biased” ball which rolls with a curve. One story attributes that development to the Duke of Suffolk in 1522, when his wooden ball split and he replaced it with a stair-banister knob that was flat on one side and could not roll straight, thus increasing the challenge and skill required to play.

But it was not until the Victorian era that the game reached its present-day mode. Three events played a large role in that progress: 1) the invention of the lawn-mower in 1830, which made maintaining a smooth, flat green both more attainable and less expensive; 2) the queen’s 1845 rescinding of the old prohibitions, which opened the game officially to all English people; and 3) the Scots (notably W.W. Mitchell, along with 200 other bowlers from various clubs) agreed upon standardized rules in 1848 and codified them into a uniform set of laws that were eventually adopted internationally.

In Part 3 next month we’ll take a brief look at more “summer games” and even quiz you on which ones would have been played during the Regency!