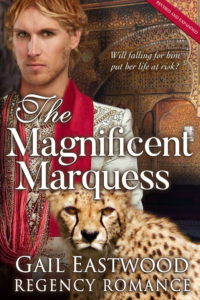

Happy 2017! I had hoped to give you a date for the re-release of The Magnificent Marquess, but I am finishing up my revisions and still aiming for the end of this month or early February. I just can’t sit on my new cover any longer –take a look!! (click on images to see them bigger)

Happy 2017! I had hoped to give you a date for the re-release of The Magnificent Marquess, but I am finishing up my revisions and still aiming for the end of this month or early February. I just can’t sit on my new cover any longer –take a look!! (click on images to see them bigger)

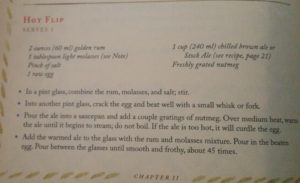

The hero in this book has lived in India for most of his life, and besides some loyal Indian servants who chose to come with him to London, he also has brought his pet cheetah, Ranee. She is the cause of some trouble right at the beginning of the story. And while you might not think the topic of cheetahs is very connected to the Regency, let me show you how it is!

When this story was first published by Signet back in 1998, some readers didn’t realize that in the early 19th century there were still (or ever had been) Asian cheetahs in India. They are gone from India (the cheetahs, not the readers) and are very nearly extinct now even in the Middle East, where they used to roam freely. I was very distressed recently to read that cheetahs of every kind are now considered endangered. But in 1816, that was not the case.

In India, cheetahs were often trained for hunting. They are, after all, the fastest animal on the planet. It almost seems like cheating!!  Just because the British were in India where the climate was quite unlike that at home doesn’t mean they were about to give up their treasured leisure pursuits. But not all cheetahs were suited to it, and that is the case with Ranee, who is much happier as a pampered companion.

Just because the British were in India where the climate was quite unlike that at home doesn’t mean they were about to give up their treasured leisure pursuits. But not all cheetahs were suited to it, and that is the case with Ranee, who is much happier as a pampered companion.

Of course, Ranee is fictional, and I went with my belief in “what could have been” when I wrote this story. Have you ever read or written something in a story that seems reasonable based on research, even though you couldn’t document that anyone ever did it? Isn’t it exciting when later you stumble across information that supports it? It’s so much easier to do research now!

The Internet was just blossoming back when I wrote the original version of this book. At that time I did not find any actual cases of cheetahs being brought to London. But do you know who had one? George III! And the artist George Stubbs took time off from painting horses long enough to paint a picture of it. Here it is:

It breaks my heart that the king’s cheetah eventually ended up in the zoo at the Tower of London, such a sad fate for a magnificent animal born to run. How long it survived there I have not been able to find out. Even though this happened some 60 years before my story takes place, pre-Regency, the king and many other people from that time were still alive during the Regency and might have remembered poor Sultan, or at least saw Stubbs’s painting exhibited at the Royal Academy.

It breaks my heart that the king’s cheetah eventually ended up in the zoo at the Tower of London, such a sad fate for a magnificent animal born to run. How long it survived there I have not been able to find out. Even though this happened some 60 years before my story takes place, pre-Regency, the king and many other people from that time were still alive during the Regency and might have remembered poor Sultan, or at least saw Stubbs’s painting exhibited at the Royal Academy.

I still haven’t been able to access much information about Sultan or even the later history of the Stubbs painting, and now I would love to know more. If you’ve ever run across this or know of an accessible source, please share!

In the meantime, please let me know in the comments what you think of my new cover? I always wished Signet had included Ranee in the original one. I hope by next month I’ll be letting you know the new version of the book, revised and expanded, is out and available!! Happy New Year, everyone!  P.S. If you are interested in learning more about cheetahs, there’s a fascinating blog that follows the story of one rescued cheetah from cub-dom to adulthood (click on any of the cheetah pix on the site’s homepage, or go here for a single post: http://sirikoi.blogspot.com/2013/09/sheba.html or here for a nice narrative version of Sheba’s story: http://www.care2.com/causes/cheetah-raised-by-humans-who-loved-her-enough-to-set-her-free.html Also here’s a link to the recent information about how endangered these beautiful cats have become today (with some more lovely photos): http://www.care2.com/causes/worlds-fastest-land-animal-is-now-racing-extinction.html

P.S. If you are interested in learning more about cheetahs, there’s a fascinating blog that follows the story of one rescued cheetah from cub-dom to adulthood (click on any of the cheetah pix on the site’s homepage, or go here for a single post: http://sirikoi.blogspot.com/2013/09/sheba.html or here for a nice narrative version of Sheba’s story: http://www.care2.com/causes/cheetah-raised-by-humans-who-loved-her-enough-to-set-her-free.html Also here’s a link to the recent information about how endangered these beautiful cats have become today (with some more lovely photos): http://www.care2.com/causes/worlds-fastest-land-animal-is-now-racing-extinction.html