In looking around for a blog topic today, I found out that the first manned hot air balloon flight happened on June 4, 1783, by the Montgolfier brothers of France! Elena would know much more about this than I would (I just started looking into the event last night!), but I thought it was fascinating. And, as someone who almost had a panic attack the one time I tried hot air ballooning (in a tethered craft!) I deeply admire anyone with such courage as to leave the ground in a time when the horse was the fastest mode of transport.

In looking around for a blog topic today, I found out that the first manned hot air balloon flight happened on June 4, 1783, by the Montgolfier brothers of France! Elena would know much more about this than I would (I just started looking into the event last night!), but I thought it was fascinating. And, as someone who almost had a panic attack the one time I tried hot air ballooning (in a tethered craft!) I deeply admire anyone with such courage as to leave the ground in a time when the horse was the fastest mode of transport.

Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etiene Montgolfier were 2 of the 16 children of a paper manufacturer in Annonay, France. The business did well, allowing Joseph to mess about with his dreamy, “impractical” ideas and the more business-like, practical Jacques to train in Paris as an architect. Until the eldest son died and Jacques was brought back to run the family business (which he made more efficient and modern, gaining a royal commendation)

In 1777 Joseph was watching laundry drying over a fire, forming pockets that made the sheets billow. He started making a few experiments in November 1782 while living in Avignon. He was thinking about the possibility of an air assault using troops lifted by the same force that was lifting the embers from the fire, which might be of use to the French military in sieges. He built a square room 1×1×1.3 m (3 ft by 3 ft (0.91 m) by 4 ft) out of very thin wood, and covered the sides and top with lightweight silk. He crumpled and lit some paper under the bottom of the box, making the contraption raise up and collide with the ceiling. Joseph wrote to Jacques”Get in a supply of taffeta and of cordage, quickly, and you will see one of the most astonishing sights in the world.” The two of them built another, larger device and gave it a test flight in December 1782. The device floated nearly 1 and a half miles before it crashed and was destroyed after landing by the “indiscretion” of passersby.

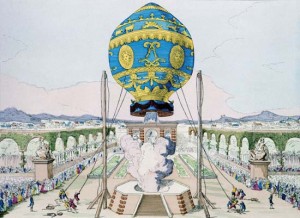

The brothers decided to make a public demonstration of a balloon in order to establish their claim to its invention. They constructed a globe-shaped balloon of sackcloth with three thin layers of paper inside. “The envelope could contain nearly 790 m³ (28,000 cubic feet) of air and weighed 225 kg (500 lb). It was constructed of four pieces (the dome and three lateral bands) and held together by 1,800 buttons. A reinforcing fish net of cord covered the outside of the envelope.” (according to Charles Gillispie’s The Montgolfier Brothers, and the Invention of Aviation.)

On 4 June 1783, they flew this craft as their first public demonstration at Annonay in front of a group of dignitaries from the États particuliers. Its flight lasted over a mile for 10 minutes, with an estimated altitude of 5,200-6,600 ft. Word of their success quickly reached Paris. Étienne went to the capital to make further demonstrations and to solidify the brothers’ claim to the invention of flight. Joseph, given his unkempt appearance and shyness, remained with the family.

On 19 September 1783, the Aérostat Réveillon was flown with the first living passengers (a sheep,a duck, and a rooster, even though the king had proposed using a couple of comvicts…) in a basket attached to the balloon: a sheep called Montauciel (“Climb-to-the-sky”), a duck and a rooster. This demonstration was at Versailles, for King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette and their court. The flight lasted approximately eight minutes for 2 miles, and landed safely after flying. I guess the passengers had no ill effects! In October, Jacques-Etienne became the first human to fly in a balloon. These early flights were a sensation. You could buy chairs with balloon backs, and mantel clocks were produced in enamel and gilt-bronze replicas set with a dial in the balloon. There was also china decorated with pictures of balloons.

The Montgolfier Company still exists in Annonay, France. In 1799, Jacques-Etienne de Montgolfier died and his son-in-law, Barthélémy Barou de la Lombardière de Canson (1774–1859), succeeded him as the head of the company, thanks to his marriage with Alexandrine de Montgolfier. The company became “Montgolfier et Canson” in 1801, then “Canson-Montgolfier” in 1807. They still produce fine art papers and digital fine art and photography supplies, sold in 120 countries.

Have you ever been in a hot air balloon?? What was it like? Would you have liked to see this first balloon launch?