Susanna here.

Today my critique partner Rose Lerner visits Risky Regencies to talk about her new release, Sweet Disorder.

In a starred review, Publishers Weekly says that “Lerner’s distinctive and likable cast of parents, siblings, reluctant suitors, and political opponents feels integral to the story…This rich and memorable Regency romance brings its setting and characters perfectly to life.”

One commenter on this post will be chosen at random to receive a free e-book of Sweet Disorder (your choice of format), and one commenter will be chosen from the entire blog tour to receive an awesome prize package that includes tie-in pinback buttons, bookmarks, bacon-scented candles, a bookstore gift card, and much, much more! (You can see the full list and pictures of her fabulous swag at her blog. This drawing is open internationally. Void where prohibited!)

Welcome, Rose!

Tell us about Sweet Disorder…

What’s risky about the story?

Nick is a beta hero. AND he’s dealing with a mild new disability, AND there are no ballrooms anywhere (except in one small scene set at the local assembly rooms). But I think the thing I’m most nervous about is that the plot revolves around party politics, always a charged topic. While the heart of the story is the romance, and while I’ve tried to avoid any Star-Trek-style heavy-handed Special Messages (although I do enjoy them on Star Trek!), and while the political parties and issues of the Regency don’t really correspond to those today, given that political radicals of the time were pushing for–gasp!–universal male suffrage…well, I just hope I don’t turn off too many readers! Or at least that there will be plenty of readers who like what I’m doing, to compensate.

Phoebe, your heroine, isn’t of the aristocracy or gentry, but neither is she the kind of desperately poor waif or urchin that in my (completely unscientific) impression as a reader we most often see for a commoner hero or heroine. Instead she feels very relatable, an ordinary person working for her living like most of us are today (only I’m very glad chores like laundry have become so much easier). How did you decide on her background?

Well, I knew I needed Phoebe to be struggling financially enough to need money from Nick’s family when she has a family crisis, and I knew I needed her to be middle-class enough that her father was a voter. In the Regency, the vast majority of voters would not be in the desperately poor category, although I’m sure there were exceptions, especially in freeman boroughs (in most other borough types there were actual income/property requirements). So I had a range to work with…and then I made her father a lawyer who did a lot of pro bono work because my mother was a lawyer who did a lot of pro bono work.

I AM SO GRATEFUL FOR MY WASHING MACHINE OMG.

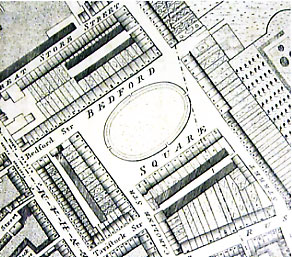

Sweet Disorder centers around a parliamentary election. Phoebe can’t vote herself, but if she marries her husband will gain that right. I gather this only happened in a select few boroughs. Can you share where you learned that this was a real thing? I was fascinated by how the political parties were known by their colors, sort of like red for Republicans and blue for Democrats today, only I got the impression that your village had its own variations. (Basically I’d be glad to hear any fun political trivia!)

This post is getting CRAZY long, but I did a blog post explaining the pre-Reform Act of 1832 political system and women’s voting rights in detail over at History Hoydens a while ago. The short version is that it may not have been THAT rare–basically in freeman boroughs, anyone who had the freedom of the city could vote. Each city and town made their own rules for how to get this freedom, but ways typically included purchase (expensive), completing an apprenticeship to a freeman, or by inheritance (the son of a freeman is a freeman) or (in some boroughs) marriage.

What that means is that in some places marrying the daughter or widow of a freeman could get a man the freedom (sometimes only during her lifetime). In Lively St. Lemeston, only the eldest daughter of a freeman who died without heirs can pass the freedom along to her husband (there was at least one borough I came across where this was the rule), because I wanted Phoebe to be the only one in her town and therefore the focus of a lot of attention during a close electoral race.

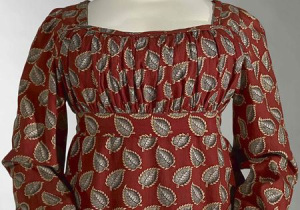

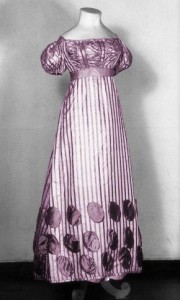

Honestly, the colors for the political parties were more like sports teams! I don’t believe the national Whig and Tory parties had particular colors (although I do vaguely remember reading about an eighteenth century party where all the Whiggish ladies wore elaborate white gowns to indicate their political stance about some issue or other). But it was very common for local political parties–which were not really branches of the national Whig and Tory parties, although they usually were loosely affiliated with one of the national parties and their supporters often voted along those lines in national elections.

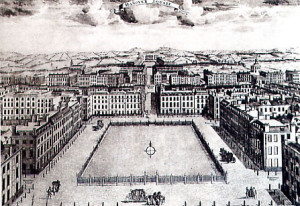

But national elections were rare (and in many constituencies, even more rarely contested) and most political activity was conducted at a local level, so one’s local political loyalties tended to come up much more often, and since most people didn’t vote, politics really was a spectator sport! People who couldn’t vote often still rooted passionately for one side or other. Elections were major events, and voters had to go to a central location to poll. So an election was really a lot like a big game day now, where you see huge groups of people in team colors hanging out, sometimes filling the street, drinking, cheering on their side, getting out of control and breaking things, starting fights with supporters of the other side, etc.

Covent Garden Market – Westminster Election, 1808. Via Wikimedia Commons.

This Rowlandson print illustrates the atmosphere nicely, I think. There seems to be an actual parade going on here, with floats and contingents from various parishes! Check out the people who’ve climbed the hustings (that distinctive slope-roofed temporary wooden structure, from which candidates gave their speeches and frequently where voters were polled) and are lying on their stomachs on the roof.

If your hero and heroine lived in 2014, what would they do with their lives? Both work in fields that still exist today, but would they follow a similar path if they had a modern array of career options?

I could see Phoebe doing the same thing–having been married to someone who owns a local newspaper and working on that while they were married, then writing children’s books. She’d probably need a day job, though. I could see her doing office/administrative work or something, especially in a law office or school. Nick…I don’t think Nick would be in the army. He was an upper-class kid with no idea what he wanted from life, and he only joined the army in the first place to spite his mother, because it sounded more interesting than the church or the law, and because you could just buy a commission. I can’t see him making the decision to go to Sandhurst (the British officer training academy). I think it’s more likely that a modern Nick would have volunteered for a British analogue of the Peace Corps.

Sweet Disorder is your first book since early 2011, after your first two books were released during Dorchester’s slow death spiral. If you’re comfortable doing so, please share what it was like to have such a long layoff.

Not fun! I spent a lot of time worrying that I would never be published again, or at least that by the time my next book came out all the momentum and buzz I got for In for a Penny would be lost.

Fortunately self-publishing took off right around the time Dorchester went under, and digital’s market share was growing dramatically (as it continues to do), so I knew that I had options if I couldn’t find another New York print publisher willing to take a chance on my books. Without that, I think I would have felt pretty hopeless.

I don’t even regret publishing with Dorchester, because I’d been trying for a long time and gotten a lot of rejections, and Dorchester got the books out there and started my career. My editor was wonderful, and she got me great reviews and really promoted the book, and every person I interacted with in the office was helpful and enthusiastic. I made lasting friends there.

But I have to admit, publishing with Dorchester scarred me too. The worst part was fielding questions from readers. Every time someone asked me where they could buy my books and I had to say that they were out of print, try interlibrary loan, and that no, I didn’t know when they’d be available again, no, I didn’t have my rights back yet, no, I didn’t know when I’d have another book out, I felt…not just sad, not even just embarrassed, but guilty. Ashamed. As if I’d done something wrong. I should have a better answer. I was letting people down.

Shame is an emotion that sneaks in and stays and is incredibly difficult to get rid of, like mold or an ant infestation. Now that I’m thinking about it, I realize that shame is kind of a running theme in Sweet Disorder. It’s an emotion with a peculiar ability to isolate people from each other, but also to connect them–because realizing that someone else shares the thing you’re ashamed of, or even just has their own secret shames and embarrassments, is one of the most liberating, intimate, powerful experiences in the world. That makes it especially interesting for romance.

Nick and Phoebe are both trying to figure out what the rest of their lives will look like. They’re both dealing with financial worries (even though Nick is from a very rich family, he’s had to leave his army career because of an injury and he’s temporarily living off the allowance he gets from his mother, which is sort of reliant on her being happy with him, and the idea of job-hunting while dealing with his new disability is really scary for him). They’re both filled with small, painful regrets, both trying to seem as if they’re calm and in control when really it feels as if everything is falling apart. I guess maybe it’s not a coincidence that I wrote this book after Dorchester.

What’s next for you?

My first two books, In for a Penny and A Lily Among Thorns, are being rereleased by Samhain in June and September. And then the second book set in Lively St. Lemeston, True Pretenses, is out early next year. It’s about a con man who decides to create a new respectable life for his beloved little brother by arranging a marriage of convenience for him with a beautiful philanthropist who needs to get her hands on her dowry. (She’s the daughter of Nick’s mother’s archnemesis Lord Wheatcroft, the head of the Lively St. Lemeston Tory Party.) But when a terrible family secret comes to light and his brother abandons him mid-scheme, the heiress demands that he marry her instead. Oh noes, what will happen?

Thank you so much for having me!

Susanna here again with a question for you readers: Which modern convenience would you miss most if you found yourself thrown back in time to the Regency? As a reminder, one commenter gets a copy of Sweet Disorder, and all are entered for her blog tour grand prize.