I am so grateful to HJ who spent a great deal of time and effort to come up with a strapline for me to send to the UK Harlequin folks for use on my author page. HJ came up with many ideas, but this one is my favorite:

Rich, ravishing, reflective – award-winning Regency romances

HJ, you definitely win the $5.00 Amazon gift card. Look for an email from me.

I looked at Chambers’ Book of Days for a blog topic for today. The Book of Days was written in 1869 and contains a “A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character.” When stuck for a topic, I often go to the online version and search by the day’s date.

I looked at Chambers’ Book of Days for a blog topic for today. The Book of Days was written in 1869 and contains a “A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character.” When stuck for a topic, I often go to the online version and search by the day’s date.

The August 5 entry tells about London Shoeblacks.

Shoeblacks or shoeshine boys appeared to go out of favor in the late Regency. Chambers talks of the last of the shoeblacks of that era, “as a short, large-headed son of Africa, rendered melancholy by impending bankruptcy, who might he seen, about the year 1820, plying his calling in one of the many courts on the north side of Fleet Street, till driven into the workhouse by the desertion of his last customer.”

During this time period, the shoeblack used a three-legged stool, and carried his tools in a large tin kettle which contained an earthen-pot filled with blacking (made of ivory black, brown sugar, vinegar, and water), a knife, two or three brushes, a stick with a piece of rag at the end, and an old wig. The wig was used to wipe the dust and dirt from the shoe before polishing.

Shoeblacks were seen on every corner of the street in London in those days. Apparently the manufacture of shoe polish by Day and Martin led to the demise of the shoeblack profession in London.

It was revived in 1851. Some philanthropists affiliated with the Ragged Schools had an idea to train boys who would otherwise be on the streets to shine shoes. They were dressed in red coats, attended a Ragged School at night and lived in dormitories.

During the Great Exhibition about twenty-five boys polished over 100,000 boots. During the first year the Shoeblack Society made £656.

Because of the Shoeblack Society hundreds of homeless boys were rescued from lives of privation or crime, but the occupation also became licensed and controlled. Unlicensed shoeblacks suffered harassment from the police.

Those boys who worked hard eventually were able to move on to other ventures, some even able to buy businesses of their own. After 30 years the Shoeblack Society earned almost a quarter million pounds. Their fame even reached the New York Times in 1881.

One might not find shoeblacks on every corner of London now, but you can still get a great shine from the stand at the Burlington Arcade

So…here’s my question for today. When was the last time you polished a pair of shoes?

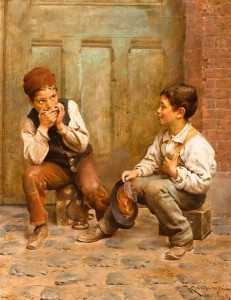

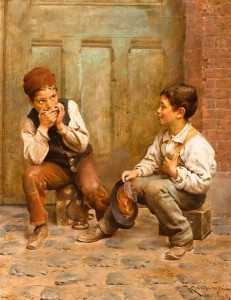

P.S. the painting above is totally inaccurate for this post. It is called “Shoeshine Boys,” and is an 1889 painting by Polish-American artist, Karol D. Witkowski)

Even though I love Regency Historical Romances, I don’t read many of them these days (although I loved my friend Mary Blayney’s One More Kiss). I can’t read them when I’m writing one, because if I get lost in that book, I won’t get lost in mine, or I may forget which book I’m lost in altogether.

Even though I love Regency Historical Romances, I don’t read many of them these days (although I loved my friend Mary Blayney’s One More Kiss). I can’t read them when I’m writing one, because if I get lost in that book, I won’t get lost in mine, or I may forget which book I’m lost in altogether.