The end of the old year must have addled my brains, for I completely forgot to write a post last Wednesday – sorry about that!!!

I hope you all had a good start into 2015! I for one, started the year doing research on food.

I love good food (cheesecake!!!), so perhaps it’s no surprise that dinners, luncheons, & teas feature frequently in my books. Researching 19th-century food is such a joy: not only are there oodles of books available on the subject (like Kristen Olsen’s Cooking with Jane Austen), but you can also easily access primary material – in other words, cookbooks! One of my favorite cookbooks from the Georian era is Frederick Nutt’s The Complete Confectioner; or, The Whole Art of Confectionary Made Easy: Also Receipts for Home-Made Wines, Cordials, French and Italian Liqueurs, &c. It was originally published in the late 18th century, and new editions appeared throughout the Regency era. The 1819 edition is available online from Google Books.

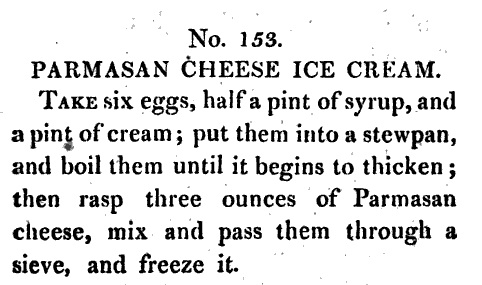

Nutt’s Complete Confectioner is just perfect when you’re looking for something to satisfy your hero’s (or heroine’s) sweet tooth: the book starts with biscuits (including chocolate biscuits, orange biscuits, and French maccaroons), continues with cakes, wafers, drops (perhaps your hero likes munching bergamot drops? Seville orange drops?), and also includes recipes for jellies, creams, ice creams and water ices (well, okay, you’d probably want to skip No. 153, “Parmasan Cheese Ice Cream”). And then, of course, there are the recipes for alcoholic beverages (elder wine, cowslip wine, orange wine, cinnamon liqueur, coffee liqueur, etc.)

For the Victorian period, there is the ever-wonderful Mrs. Beaton, whose cake recipes often include breath-taking amounts of eggs (16 for the Rich Bride Cake!) and who also gives you advice on the duties of servants – perfect! Moreover, Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management includes suggestions for seasonal dinner menus. And while there are a few dishes I really wouldn’t want to see on the table in front of me (boiled calf’s head with tongue and brains, anybody?), I’d be more than happy with the roast ribs of beef, the grilled mushrooms, with the Charlotte Russe and the rhubarb tart (yum!).

For the Victorian period, there is the ever-wonderful Mrs. Beaton, whose cake recipes often include breath-taking amounts of eggs (16 for the Rich Bride Cake!) and who also gives you advice on the duties of servants – perfect! Moreover, Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management includes suggestions for seasonal dinner menus. And while there are a few dishes I really wouldn’t want to see on the table in front of me (boiled calf’s head with tongue and brains, anybody?), I’d be more than happy with the roast ribs of beef, the grilled mushrooms, with the Charlotte Russe and the rhubarb tart (yum!).

But, alas, at the moment I’m not doing research on 19th-century food. I am doing research on Roman food.

Oh dear, Roman food.

*hides behind her couch and whimpers*

First of all, there is the infamous garum, the stuff the Romans apparently poured over almost anything – like ketchup. Only, well, garum wasn’t made from tomatoes, but from fish.

Rotten fish.

In his De re coquinaria (On the Art of Cooking), Apicius included a particularly nice recipe for garum: take gills, fish intestines, fish blood, salt, vinegar, parsley and wine, throw everything into a vessel, and leave it out in the sun for three months. Afterwards, stain and bottle (= fill into an amphora).

And as if rotten fish sauce wasn’t bad enough, there is also the stuff that the Romans ate at posh dinner parties.

Think sow’s udders stuffed with giant African snails.

Or fried dormice rolled in honey and poppy seeds.

But hey, if you don’t like something, you can always pour garum over it!

[Note to self: Should you ever write another historical set in Roman antiquity, DON’T GIVE ANY OF YOUR MAIN CHARACTERS POSH FRIENDS!!!!! No extravagant Roman dinner parties EVER again!!!!]