Today I’ll continue the dance series I began on July 6, with some notes about the cotillion and the quadrille, dances which were common in the early Regency and the late Regency, respectively. While there is a great deal of overlap in some characteristics of these dances, their prevalence in the ballroom does not seem to have overlapped much at all.

COTILLIONS

Jane Austen wrote to her niece Fanny in 1816, “Much obliged for the quadrilles, which I am grown to think pretty enough, though of course they are very inferior to the cotillions of my own day.” Jane was past her dancing prime by then and was referring to music sheets, but as so often happens even today, was not a fan of the “new” style of dancing that the younger people loved.

The Cotillion was a French country dance for four couples popular in England in the late 18th century. While it often began with a circling figure and included later small circles, most of the dance was performed in a square, with various “changes”, or figures that moved in and out of that main formation and allowed for changes of partners.

Because the cotillions came from France, many kept their French names. The only dance Jane Austen ever mentions by name, “La Boulangerie” is a cotillion. Here is a video so you can see what it was she so enjoyed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLUzvSXguQY

There were many various types of cotillion dances: “waltz cotillions” and “allemande cotillions” for instance. They included some figures also commonly found in English country dances and reels, and later the quadrilles, so there is a shared basis between the types of dances.

For instance, four of the basic quadrille segments are also found in cotillions: Les Pantalons, L’Eté, La Poule and La Pastorale. Many steps are also shared, but in style and music the dances are quite different. Quadrille enthusiasts denounced the cotillion as old-fashioned and “belonging with the ancient minuet.”

The word “cotillion” changed during the 19th century from referring to the specific type of dances to the more modern usage, referring instead to a dance event, even specifically to a dance event for debutantes. Just know that during the Regency era, that was not what it meant!

QUADRILLES

Captain Gronow wrote in his memoirs about the first appearance of the Quadrille at London’s elite social venue, Almack’s: “In 1814, the dances at Almack’s were Scotch reels and the old English country-dance; and the orchestra, being from Edinburgh, was conducted by the then celebrated Neil Gow. It was not until 1815 that Lady Jersey introduced from Paris the favourite quadrille, which has so long remained popular.”

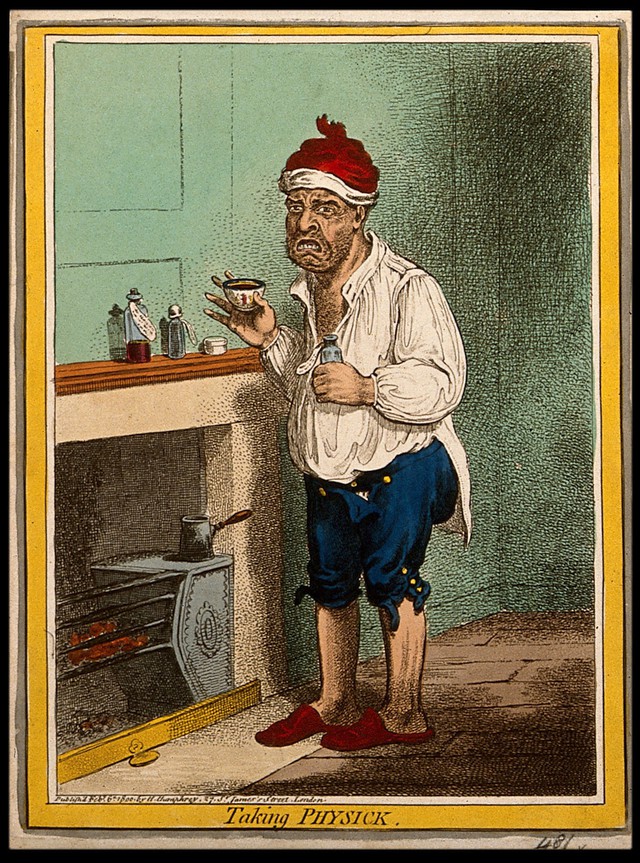

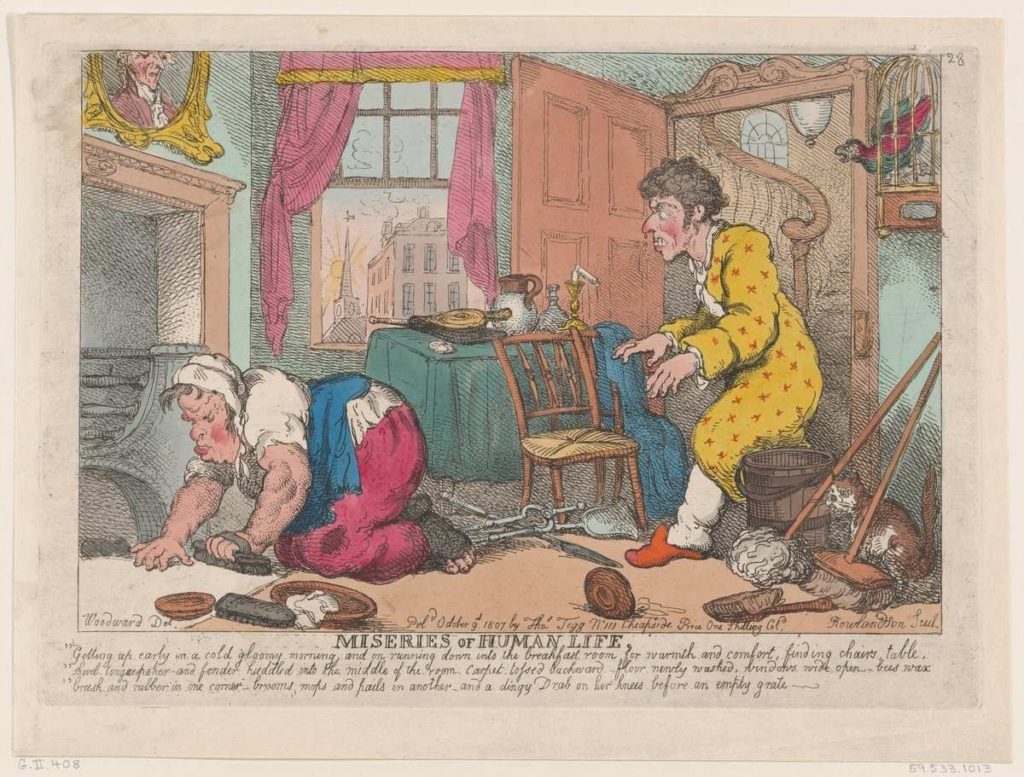

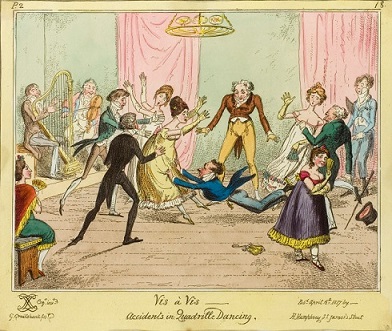

The quadrille became a craze, so popular that it overtook all other forms of dance being done at this time, except for the waltz (topic for Part 3 of this series), introduced at about the same time. Cartoonists of the day, such as Gilroy and Cruikshank, could not be expected to resist ridiculing such a vibrant fad, especially as it required some skill and practice. “Accidents while dancing the Quadrille” was a popular caption.

Like the cotillion, this was a dance form with four couples arranged in a square. Unlike the cotillion, it consisted of five sections or movements, each with its own complicated sequence of figures and music, with differing time signatures. Also unlike the cotillion, in the quadrille, the couples took turns performing the steps, with the head couples leading and the side couples resting until their turn. (Given the exertion required and the length of the dances, this was no doubt a blessing!)

This video gives a good sense of the dance –watch as much as you wish, just know it lasts 11 minutes and 19 seconds! Paine’s First Set of Quadrilles (1815) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VSD37PF2_Dw

Here is a video that shows “The Mozart Cotillion” being danced at Chawton House (yes, I thought you’d like that!) 🙂 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YEsAijdGT20

I hope you are enjoying these dance notes and finding them helpful to visualize Regency dancing for your reading or writing pleasure! Part 3 on the Waltz will be posted on July 25.