I believe that writers of historical fiction need this same type of knowledge base. I’ve occasionally been vilified/attacked for pointing out that some cherished facet of Romancelandia is, in fact, erroneous (men wearing wedding rings), anachronistic (scones in Regency settings), or just plain wrong (engagement announcements during the Georgian era). I’m open to being shown that I’m wrong, but doing so requires documentation (which does not consist of point out that Heyer did it in her books).

I grew up in the world or re-enactors, so I have very definite ideas about what research is and what it takes to document the minutia of everyday historical life. In the re-enactment community, we talk about things being “documented” and “undocumentatable” all the time. We harp on it constantly, and argue over what is and what isn’t. We disagree about interpretations and conclusions. It’s a constantly evolving hobby, and this is part of the fun (really . . . no, really). And since we’re attempting “living history” we have to know not just the dates of battles and the names of major historical figures, but the little things like what food stuffs were available and, more importantly, common for the class and location of our persona.

There are three kinds (or levels) of sources/documentation: Primary, secondary and tertiary (and then there’s art).

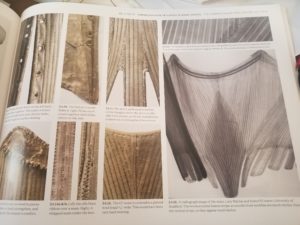

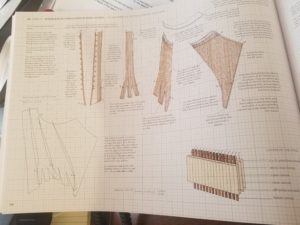

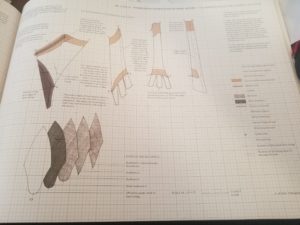

Primary sources are actual items from the period (what historians call “extant”). A hat. A shoe. A saddle. Also in the primary grouping are period documents like letters, journals, newspapers, household inventories, and period books (cookbooks are invaluable). Though you have to be careful with some of these, because they function almost like secondary sources, since they are one person’s viewpoint and they often require context in order to obtain full understanding (into this group I consign the single source [a letter] that mentioned French women dampening their petticoats to make them cling; it was by an outraged Englishman who didn’t like travel or the French and I without any other source to back it up, I call shenanigans).

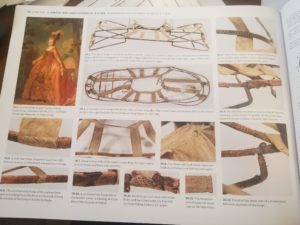

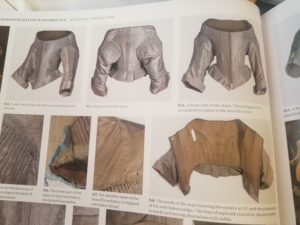

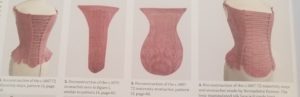

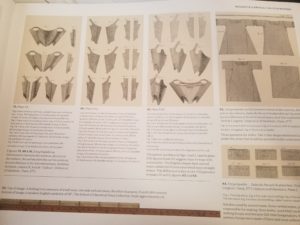

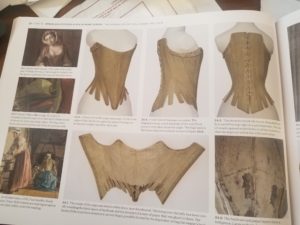

Secondary sources are frequently underused in the writing community (with the exception of the Oxford English Dictionary), but re-enactors live for them! If you really want to know how the clothing fastened, what it looked like, what fabrics were used, what the layers were, Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion: Englishwomen’s Dresses and Their Construction, c. 1660-1860 (where she deconstructs and details historical garments) is far more useful than an overview like 20,000 Years of Fashion by François Boucher. Overviews, of course, have their own purposes, and Boucher’s book is on the list of “must haves” for every writer in my opinion, but it doesn’t lead you into the lived history the way Arnold’s work does.

The next level down is tertiary. These are the sources that most writers and students are using: All the biographies and history books that we snap up in the non-fiction section of the bookstore. You have to be careful with tertiary sources. In the re-enactment community, these are not considered documentation in and of themselves. Only primary and secondary count for that (hence some of the arguments). Only tertiary works which are extensively documented should ever be relied upon (look for authors who are respected experts in their field and for books with lots of citations). Often, something that looks great on the surface will be found to be less than useful when you dig in. An example of this is something like What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew. The book skims the surface of many topics and fails to date them specifically within the 19th century, resulting in a mash-up of the late-Georgian, Regency, Romantic and Victorian eras. It’s a fun book, but it’s not all that helpful for an author trying to find out what her character might have served at tea (especially as afternoon tea only became an established “thing” in the Victorian era). Another is An Elegant Madness, which seems like a great book, but upon closer inspection is riddled with errors that leave my in doubt of pretty much everything the author says (such as the author’s inability to keep Frances Villiers, wife of the 4th Earl of Jersey and her daughter-in-law Sarah Sophia Child Villiers, wife of the 5th Earl of Jersey straight; some major blunders about who was having an affair with whom).

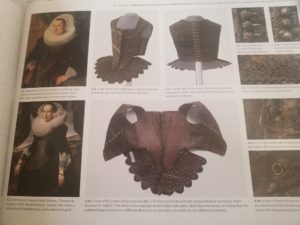

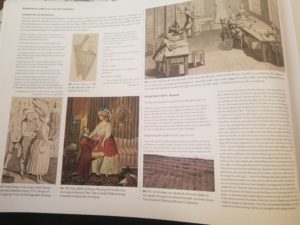

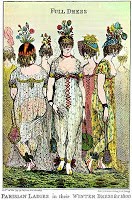

Lastly, we come to art. This area can be tricky. The problem is that unlike having the physical item in your hand (for example, the actual dress), you’re looking at an artist’s interpretation of that item (so these act a lot like secondary and tertiary sources). Add into the mix that much of the art we look at is highly stylized, allegorical, political, and/or farcical (so the see-through dress over the shift with a “display” hole cut out over the bum can’t be taken as a literal example of the clothing being worn in France c. 1800) and it’s sometimes hard to know what you’re really looking at. And then there is the problem of reproduction. A lot gets lost when the paintings are photographed and reproduced. Fine details can entirely disappear. And often you have to have a strong background in the period already to know what you’re looking at, which makes art useful for the knowledgeable historian, but problematic for the novice (and it tends to be the go-to source for many novices, since it appears to be the most accessible form of documentation).

The one thing that should NEVER be cited as documentation is a work of fiction. Not my books. Not Diana Gabaldon’s books. Not Bernard Cornwell’s books. Not Georgette Heyer’s book. If you see something in a book that intrigues or inspires you, make a note of it and then double check it. Authors are fallible. We make mistakes. We fudge things. We cling to our own preconceived notions or to “facts” we were taught (which often have built-in cultural, religious, or socioeconomic biases of their own).

Some things are open to interpretation, and there is no “right” or “wrong” answer. For example, I like writing about strong, fast, wild, unusual women. Because these kind of women interest me, I read a lot of biographies and histories about the ones that really existed. Books like Jo Manning’s My Lady Scandalous (about courtesan Grace Elliot, aka Dally the Tall), Hallie Rubenhold’s The Lady in Red (about Lady Worsley’s disastrous marriage and divorce), the illustrated version of Amanda Forman’s Georgiana (about the Duchess of Devonshire), and Janet Gleeson’s Privilege and Scandal (about Lady Bessborough). I also read things like Harriette Wilson’s memoir, Sex in Georgian England by A.D. Harvey, and Broken Lives by Lawrence Stone.

All of this feeds in to my version of Georgian England, which is very different from the one created by Georgette Heyer or one created by one of my current peers who prefers to write ingénues or guttersnipes. Any of us being asked to justify our preference is ridiculous in my opinion, but this is utterly different than someone asking if it was really possible for Jo Beverley’s heroine Elfled Malloren to have a pair of lace stockings (and yes, it was; there’s an extant [primary source] example in a museum in Germany that belonged to Madame de Pompadour).