The habit of taking snuff is one of those areas of very authentic period life that seem distasteful to our modern sensibilities. If I wrote a hero who took snuff, be honest –wouldn’t your reaction be “eeeuwww”? He would instantly seem less attractive, wouldn’t he? Snuff-users, if we have any in our stories at all, are more likely to be dandy-ish best friends or even perhaps villains.

The habit of taking snuff is one of those areas of very authentic period life that seem distasteful to our modern sensibilities. If I wrote a hero who took snuff, be honest –wouldn’t your reaction be “eeeuwww”? He would instantly seem less attractive, wouldn’t he? Snuff-users, if we have any in our stories at all, are more likely to be dandy-ish best friends or even perhaps villains.

As fiction writers, we authors always walk a fine line between recreating an accurate picture of the historical world our characters live in and the attitudes of the modern age we and our readers inhabit. Today we know the dangers of using tobacco and the addictive nature of nicotine. I have to admit, after recently visiting a historic snuff mill near where I live (birthplace of American artist Gilbert Stuart), I came away wondering why more of the snuff-using fashionable people in our period didn’t all have brain cancer! (More on this below)

That said, I thought I might share a glimpse into snuff and the process of making and using it, since it actually was such a popular habit. Did you know that Queen Charlotte (Prinny’s mother) was such a snuff fan that she had an entire room at Windsor set aside for her snuff supplies? Or that she was called “snuffy Charlotte” by some (clearly irreverent) subjects? Prominent snuff-users in our period included Keats, who penned the line, “Give me wine, women and snuff, until I cry out – hold, enough!”, also Wellington, Nelson, Napoleon, and the Prince Regent himself, who had his own proprietary blend. Members of Parliament would take snuff before debating matters, and to this day a communal snuff container is provided in the House of Lords.

Snuff is dried, cured tobacco ground into a powder of varying consistencies and taken by inhaling through the nose. A special grinding apparatus is used to achieve the fine powder. Its history traces back to ancient times in Brazil, where the Spanish first encountered it and brought it back home. From there, the French picked it up and spread its use to the rest of Europe and even into the Far East. As its use became more and more popular, it grew from a luxury only for the rich to a habit also shared with the professional middle class. In general it was never adopted by the poor who smoked their tobacco instead.

Like tea at this period, snuff was blended to unique and very individual tastes. The types of original tobacco plants could vary, as well as the many different methods used for curing it. Many additional ingredients might be combined with the various kinds of dry ground tobacco to affect the scent, which lingered in the nose long after the initial fast “hit” of the nicotine. Spices, fruits, flowers and more substances were all used for this purpose. Users took pride in their own specific recipes. Prinny was hardly alone in having his own blend, although others might not have the power and position to attach their name to theirs.

Like tea at this period, snuff was blended to unique and very individual tastes. The types of original tobacco plants could vary, as well as the many different methods used for curing it. Many additional ingredients might be combined with the various kinds of dry ground tobacco to affect the scent, which lingered in the nose long after the initial fast “hit” of the nicotine. Spices, fruits, flowers and more substances were all used for this purpose. Users took pride in their own specific recipes. Prinny was hardly alone in having his own blend, although others might not have the power and position to attach their name to theirs.

Snuff was most often taken by holding a pinch between the thumb and index finger, or placing a small amount on the back of the hand to “snuff”. Sometimes rabbits’ feet were used to wipe away the residue under the nose. (Sneezing was considered the sign of a beginner, although many snuff sellers also sold handkerchiefs.) Enough people placed their pinch of snuff in the concave space between the wrist and outer base of the thumb created by cocking one’s thumb out that the spot acquired the anatomical name “snuff box”.

Snuff was most often taken by holding a pinch between the thumb and index finger, or placing a small amount on the back of the hand to “snuff”. Sometimes rabbits’ feet were used to wipe away the residue under the nose. (Sneezing was considered the sign of a beginner, although many snuff sellers also sold handkerchiefs.) Enough people placed their pinch of snuff in the concave space between the wrist and outer base of the thumb created by cocking one’s thumb out that the spot acquired the anatomical name “snuff box”.

Actual snuff boxes, however, were a necessity for users, and very quickly became status symbols.  Because dried snuff loses its flavor quickly when exposed to air, portable pocket-sized boxes that held only a day or two’s supply were needed as well as larger boxes at home, or for communal use. Pocket snuff boxes were often given as gifts, the more elaborate the better.

Because dried snuff loses its flavor quickly when exposed to air, portable pocket-sized boxes that held only a day or two’s supply were needed as well as larger boxes at home, or for communal use. Pocket snuff boxes were often given as gifts, the more elaborate the better. Boxes were made by jewelers and goldsmiths, made of gold, silver, tortoise shell, ivory and many other materials, decorated with jewels, portraits, mosaics, and more. The famous jewelers Rundell & Bridge received £8,205 for snuff-boxes given as gifts to foreign dignitaries at Prinny’s wedding.

Boxes were made by jewelers and goldsmiths, made of gold, silver, tortoise shell, ivory and many other materials, decorated with jewels, portraits, mosaics, and more. The famous jewelers Rundell & Bridge received £8,205 for snuff-boxes given as gifts to foreign dignitaries at Prinny’s wedding.

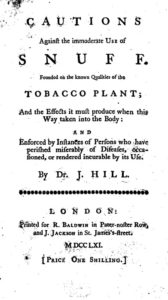

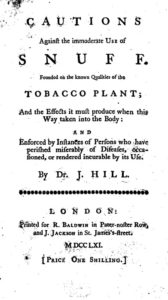

Snuff was considered by many to have beneficial medicinal properties. Catherine d’Medici used snuff to combat migraines. People believed snuff could protect them from plague and cure failing eyesight. Some modern studies have concluded that snuff is a “safe” alternative to smoking cigarettes, because it doesn’t involve the tar and carbon products from being burned and it doesn’t impact the lungs. However, warnings against snuff usage also have a long history.  It was banned at various times, and John Hill published his Caution against the Use of Snuff in 1761. People could see for themselves the damage sometimes done to the inside of the nose. The cancer-causing tobacco chemicals can have unhealthy effects on the nasal passages and sinuses they touch, and the stimulant chemicals can still raise the risks of heart-related problems such as high blood pressure, heart attack and stroke. Despite the fast route of nicotine directly to the brain, brain tissue itself is not in direct contact with the snuff, so brain cancer isn’t a risk. Throat and stomach cancer can be, when some of the powder travels from the nose to those lower areas.

It was banned at various times, and John Hill published his Caution against the Use of Snuff in 1761. People could see for themselves the damage sometimes done to the inside of the nose. The cancer-causing tobacco chemicals can have unhealthy effects on the nasal passages and sinuses they touch, and the stimulant chemicals can still raise the risks of heart-related problems such as high blood pressure, heart attack and stroke. Despite the fast route of nicotine directly to the brain, brain tissue itself is not in direct contact with the snuff, so brain cancer isn’t a risk. Throat and stomach cancer can be, when some of the powder travels from the nose to those lower areas.

I was surprised to learn, while researching this topic, that snuff use is on the rise again, popular among ex-smokers and others who haven’t kicked the nicotine addiction. A “less-bad” way around the smoking bans, I suppose. Dry snuff is closely related to “moist snuff”, also called dipping tobacco, which is placed inside the lip and is quite popular among professional sports players. Drug-screening doesn’t test for or count the addictive stimulant nicotine among the forbidden substances for these people. For an entertaining and interesting foray into the world of modern snuff users, read an excerpt posted by writer Julian Dutton on his blog, from his book titled The Bumper Book of Curious Clubs. Snuff has also been ridiculed by none other than the comedian Stephen Fry –check his youtube video .

Did you know taking snuff was on the rise again? Did you know that the phrase “up to snuff” originally meant someone who was mentally alert, smart –as in someone whose brain was stimulated by nicotine? How do you feel about period characters who indulge in taking snuff?