I’d like to share some research done at The Republic of Pemberley regarding the ways in which our hero and heroine can marry, and particularly the ubiquitous Special License. The researcher here is Julie Wakefield, a lawyer in England as well as a scholar of Georgian period. Julie is no longer with the web site, but her legacy lingers.

I’d like to share some research done at The Republic of Pemberley regarding the ways in which our hero and heroine can marry, and particularly the ubiquitous Special License. The researcher here is Julie Wakefield, a lawyer in England as well as a scholar of Georgian period. Julie is no longer with the web site, but her legacy lingers.

As this is a Jane Austen web site, you’ll find most references to her work and her time.

There were three methods of marrying legally in England and Wales in Jane Austen’s day. Marriage in England and Wales was regulated by the Marriage Act of 1753, known as Hardwicke’s Marriage Act after the Lord Chancellor, Lord Hardwicke who introduced and oversaw the passage of the Act in Parliament. The Act was controversial as it was the first attempt by Parliament to regulate the legality and form of marriage, something that has previously been subject to the control of the Church. The reason for the act was the great uncertainty and difficulties experienced during the mid 18th century by the various methods of getting married. Lord Hardwicke’s act was designed to clarify the law, to prescribe the methods by which people would marry, and to provide punishments for anyone who flouted the new regulations regarding marriage and the recording of the ceremonies.

From 1754 (when the Act came into force) it was only possible to marry in one of three ways. By the reading of banns, by Common License or by Special license. The act made attempts to marry in any other fashion- e.g. by verbal contract, a clandestine marriage, or under the auspices of a so-called Fleet marriage, unlawful, and anyone performing a marriage in this way could be subject to the death penalty, or transported for a period of 14 years (see Section 16 of the Act).

Marrying after the reading of banns. Provided both parties to the marriage were over 21 or had their respective parents consent if they were under age, then after giving 7 days notice to their priest, banns would be read for three successive Sunday in both of their parishes, to advertise the fact that their marriage was to take place. The marriage (and this was a requirement for all marriages by banns or by license) had to be performed before two witnesses. The marriage would then be immediately recorded in a register in a form prescribed by Section 15 of the Act, which was to be kept and maintained in proper order by the priest at the church. The reason for all this publicity and recording was to ensure that the marriage was known to have taken place and that there was evidence of it having occurred, should anyone attempt to deny the existence of the marriage in the future.. There were objections raised to this procedure being introduced by many people in Parliament during the passage of Hardwicke’s bill. The fact that a couples nuptials were being advertised in public was perceived to be unseemly. Horace Walpole was appalled by this situation. He wrote to a friend as follows: How would my Lady A—– have liked to be asked in a parish church for three Sundays running? I really believe that she would have worn her widows weeds for ever, rather than have passed through so imprudent a ceremony. (quoted in The Life of Lord Chancellor Hardwicke, Volume 2 pp 486-7, written by G Harris.)

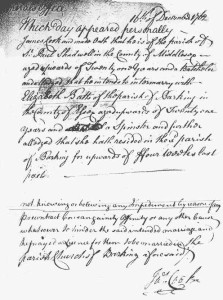

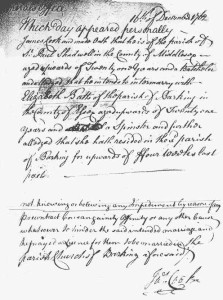

Capt. Cook’s Marriage Allegation when applying for a Common License

For those who objected to such publicity there was another route to take: marriage by Common License obtained from a Bishop. To obtain a common license, which enabled the couple concerned to marry in a nominated parish church, without the necessity of the banns being read, the applicant, usually but not always, the bridegroom, had to submit an application called an allegation to the appropriate Bishop, stating who was to be married, where,and that they had the requisite consents, or were of age. If they were under age, written consent of the parents had to be submitted. In addition, until 1823 a bond (a pledge of money) was also required, which was to be forfeit if any of the facts in the allegation were subsequently found to be untrue. Most people with any pretensions to gentility married by this route, to avoid the publicity and delay occasioned by taking the reading of the banns route to matrimony.

Special Licenses were issued by the Archbishop of Canterbury, from the Office of the Master of Faculties. Again, allegations had to be made in written from to obtain a license. The big difference between Jane Austen’s time and ours (until very recently) is that a special license enabled a couple to marry, not in a parish church, but anywhere they wished, for example, the bride’s home. A Special License therefore was very desirable for anyone who wished to have absolute privacy when marrying. In view of remarks like that made by Horace Walpole above, one can see why this was appealing to eighteenth century. A Special license was valid for six months from its date of issue, which was recorded by the Faulty office. However, further research into Special Licenses indicates that they might not be very easily obtainable.

Very few Special Licences were issued prior to the 20th century- in fact 99% of all marriage licenses issued before 1900 were Common Licenses.

In a number of cases the residential requirement was fulfilled merely temporarily or even only on paper to ( just about) meet the requirements. There was nevertheless, a rise from eleven Special Licenses in 1747 to fifty in 1757, probably as a result of Hardwicke’s emphasizing that under a Common License a couple should only marry within the parish of one of them. Such a five fold increase albeit to an extremely low absolute number, caused Archbishop Secker to panic and in 1759 to issue some guidelines whereby only Peers, Privy Councillors, Members of Parliament, barons and knights should be married with Special Licenses.

He also expected couples to marry within the normal canonical hours. Special licenses were also intended for a couple to marry in a place with which they has a real attachment, not a mere fascination. (from Christian Marriage Rites and Records by Colin R Chapman).

There you have it. The three ways in which our couples might be married, other than elopement to Scotland; the Special License not as widely available or widely used as our romances would have us believe.

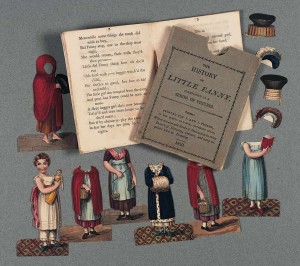

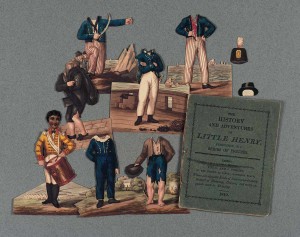

Today I’m talking about paper dolls of the Regency period, but not the fashion figures that originated in France and were adopted by dressmakers and their clients, and their clients’ children in the 1790s. Paper dolls specifically for children were created and published by Samuel and Joseph Fuller in a series of paper doll booklets–figures that dress and undress–and sold at their shop The Temple of Fancy on Rathbone Place in London. Attracting an upperclass clientele, the shop also sold prints and painting materials and supplies.

Today I’m talking about paper dolls of the Regency period, but not the fashion figures that originated in France and were adopted by dressmakers and their clients, and their clients’ children in the 1790s. Paper dolls specifically for children were created and published by Samuel and Joseph Fuller in a series of paper doll booklets–figures that dress and undress–and sold at their shop The Temple of Fancy on Rathbone Place in London. Attracting an upperclass clientele, the shop also sold prints and painting materials and supplies. I have seen a reproduction copy of Little Fanny and the storyline is depressingly moral. Little Fanny is far too interested in clothes and learns the virtues of plain living and hard work. Another title, Ellen, or, The Naughty Girl Reclaimed, pretty much speaks for itself.

I have seen a reproduction copy of Little Fanny and the storyline is depressingly moral. Little Fanny is far too interested in clothes and learns the virtues of plain living and hard work. Another title, Ellen, or, The Naughty Girl Reclaimed, pretty much speaks for itself. Just by looking at this you can see that Henry has a whale of a time, and you can view the book online here. First, he’s stolen by gypsies (moral lesson on inattentive nursemaid included) and becomes a beggar, then a chimney sweep, a drummer boy, and a sailor, rising through the ranks to return to England with fame and fortune. Huzzah!

Just by looking at this you can see that Henry has a whale of a time, and you can view the book online here. First, he’s stolen by gypsies (moral lesson on inattentive nursemaid included) and becomes a beggar, then a chimney sweep, a drummer boy, and a sailor, rising through the ranks to return to England with fame and fortune. Huzzah!