On this day in 1814, the Treaty of Fontainebleu deposed Napoleon and sent him into exile to the island of Elba. He escaped just under a year later, set sail for France, and in one of those unexpected twists of history, returned to power. No one’s quite sure how he managed to escape, but Napoleon was a man of great energy and industry, and although contemporary cartoons depict him as a disconsolate exile on a rocky island, that was artistic license.

On this day in 1814, the Treaty of Fontainebleu deposed Napoleon and sent him into exile to the island of Elba. He escaped just under a year later, set sail for France, and in one of those unexpected twists of history, returned to power. No one’s quite sure how he managed to escape, but Napoleon was a man of great energy and industry, and although contemporary cartoons depict him as a disconsolate exile on a rocky island, that was artistic license.

Now one of the many differences between the rest of us and the Corsican Monster is that if we were living in a castle in this sort of scenery, we’d grit our teeth and stay put. But not Napoleon. Apart from plotting his escape, he was quite busy as Emperor of Elba, carrying out social and economic reforms. He had a personal escort of 1,000 men, a household staff, and 110,000 subjects.

Now one of the many differences between the rest of us and the Corsican Monster is that if we were living in a castle in this sort of scenery, we’d grit our teeth and stay put. But not Napoleon. Apart from plotting his escape, he was quite busy as Emperor of Elba, carrying out social and economic reforms. He had a personal escort of 1,000 men, a household staff, and 110,000 subjects.

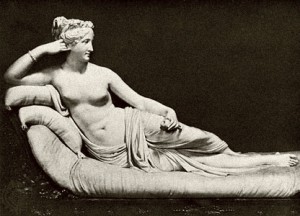

But it was a time of great misery for Napoleon, the man who’d once had almost all of Europe at his feet. The Treaty of Fontainbleu also sent his wife and son to Vienna. Napoleon was so distraught he attempted to commit suicide with a vial of poison he carried, but the poison was old and only made him sick. Shortly after his arrival, he learned of the death of the former Empress Josephine.

It’s possible his English guardians on the island aided, or at least turned a blind eye to, Napoleon’s escape plans. The restored French monarchy was proving unsatisfactory, which meant that once again the balance of power in Europe was threatened. This is discussed in this fascinating article, A Sympathetic Ear: Napoleon, Elba, and the British, which also explores the phenomenon of Napoleon as tourist trap.

British seamen proved to be keen visitors. Indeed, Napoleon had embarked for Elba on April 28th, aboard the frigate HMS Undaunted, whose captain, Thomas Ussher, wrote home on May 1st: ‘It has fallen to my extraordinary lot to be the gaolor of the instrument of the misery Europe has so long endured’. By the end of the month, the man whom Ussher could not even bring himself to name had become his ‘bon ami’, and had given him 2,000 bottles of wine, and a diamond encrusted snuffbox. In return Ussher presented Napoleon with a barge, which he flatteringly reserved for his own exclusive use.

Napoleon landed in Cannes on March 1, 1815 and declared:

I am the sovereign of the Island of Elba, and have come with six hundred men to attack the King of France and his six hundred thousand soldiers. I shall conquer this kingdom.

As he progressed through France, soldiers sent to attack him instead joined him, so that he made a triumphant return into Paris on March 20. There’s a great first-hand account of his arrival here.

So, if you’d gone to visit Napoleon on Elba with the expectation that he’d probably give you lots of wine and a diamond-encrusted snuffbox, what would you take him as a gift?

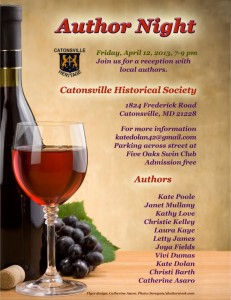

Now onto shameless self-promotion. If you’re in Maryland, I’m going to be signing tomorrow at the Catonsville Historical Society, 7 – 9 pm in the company of some excellent authors. Looks like there will be some wine too!

Now onto shameless self-promotion. If you’re in Maryland, I’m going to be signing tomorrow at the Catonsville Historical Society, 7 – 9 pm in the company of some excellent authors. Looks like there will be some wine too!