Elena, Regency Research Nerd, back for more myth-busting on the history of pregnancy and childbirth.

Elena, Regency Research Nerd, back for more myth-busting on the history of pregnancy and childbirth.

#3: Babies were born in the same ancestral bed where previous generations were born, consummated their marriages and died.

No! I’ve seen this concept many times, and I can’t decide if it gives a sweeping sense of history or is just gross.

Fabric was expensive and childbirth is messy. I won’t go into details for fear of offending the squeamish and scaring male visitors from the blog. So let me just add three words–“No rubber sheets”.

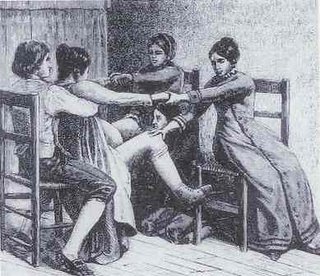

From the earliest times until well into the 19th century, most women usually gave birth in upright or semi-upright positions: squatting, standing, kneeling, sitting on the lap of a midwife or husband or in a birthing chair or stool.

However, from the 17th century or so toward “our” period, male obstetricians (called accoucheurs) who attended ladies, were beginning to move away from the birthing chair and/or redesigning it. Ladies (as opposed to working class women) were regarded as more delicate, and recumbent positions were increasingly recommended for them.

During the Regency, ladies usually gave birth in a specially designed birthing bed or cot, which was often portable and could be shared between friends.

The recommended position was the “Sims” position: woman on her side, knees drawn up, doctor BEHIND her. The lack of eye contact was supposed to preserve modesty and prevent embarrassment.

By Victorian times the “lithotomy” (on the back, legs up) position was more common, making for easier access for the doctor though not the best biological position for the woman. Conversely to Regency doctors, Victorian doctors worked under sheets by feel alone and maintained eye contact with their patients to prove they were not, um, peeking. Seems creepy to me.

Thanks for indulging me, everyone! Next week: husbands in the delivery room.

Elena

LADY DEARING’S MASQUERADE, an RT Reviewers’ Choice Award nominee

www.elenagreene.com