I have one week left on my revisions deadline for Listen to the Moon at the moment and a lot of work still to do, so I’m updating and reprinting an old post from my blog—a very topical one, because as I’m sure you’ve heard, this week is the bicentennial of Waterloo. Now, of course the battle was a few days ago, on June 18th, but the news didn’t reach England right away…

This post was inspired by one of those perennial discussions about accuracy in historical romances over at History Hoydens. As you can see from my looong comment, this is something I’ve given a lot of thought to yet totally failed to come up with a coherent policy. I evaluate anachronisms on a case-by-case basis! My anachronism ethics are situational!

But you know what I do hate unequivocally? Apocryphal historical anecdotes repeated as fact. Like how Columbus wanted to prove the world was round (I was taught this in elementary school! It makes me FURIOUS!), or how Queen Victoria didn’t believe in lesbians (this myth is not even that old, it originated in 1977). Now this is frequently a mistake made in good faith but I think that is what annoys me the most—how these lies become so ubiquitous they completely obscure the truth. The truth matters! Which leads me to…

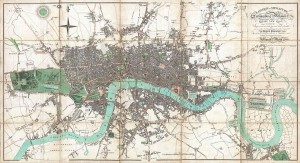

The news of Waterloo. My spy romance A Lily Among Thorns is set in London in the two weeks before the battle.

But…they’re not actually the two weeks before the battle. They’re the two weeks before the news of the battle reached London, late on the night of Wednesday, June 21st. The news quickly spread, turning into an impromptu parade through the streets of London. It must have been so thrilling!

Of course, Nathan Rothschild knew about the outcome of the battle first.

The popular story is that he went to the ‘Change and purposely led traders to believe he knew the battle had been lost. There was a panic and he was able to buy up “consols” (OED: “An abbreviation of Consolidated Annuities, i.e. the government securities of Great Britain”) at a very low price, seizing control of the Bank of England and making his fortune.

I totally believed this! You read about it everywhere! It’s in Georgette Heyer’s A Civil Contract! (Just another reason to dislike that book.) I included it in the first draft of A Lily Among Thorns. But oops, it is FALSE. The story originated in an anti-Semitic pamphlet in 1846, a clear relative of theories that Jews secretly run the government and/or the economy.

(The post I just linked to, by the way, also makes it clear that Rothschild was not the only person in London to have early news of the battle and that both word-of-mouth and printed rumors were circulating freely by Wednesday morning.)

Here’s what The House of Rothschild: Money’s Prophets 1798-1848 by Niall Ferguson has to say:

No doubt it was gratifying to receive the news of Napoleon’s defeat first, thanks to the speed with which Rothschild couriers were able to relay a newspaper version of the fifth and conclusive extraordinary bulletin—issued in Brussels at midnight on June 18—via Dunkirk and Deal to reach New Court [the location of the Rothschilds’ bank’s London branch] on the night of the 19th. This was just twenty-four hours after Wellington’s victorious meeting with Blücher on the battlefield and nearly forty-eight hours before Major Henry Percy delivered Wellington’s official dispatch to the Cabinet as its members dined at Lord Harrowby’s house (at 11 p.m. on the 21st.) Indeed, so premature did Nathan’s information appear that it was not believed when he relayed it to the government on the 20th; nor was a second Rothschild courier from Ghent.

He then explains that Waterloo was actually financially disastrous for the Rothschilds, who were financing the British army and had all their money tied up in things that were suddenly no longer necessary—and no longer likely to be paid for by the government.

In London, a frantic Nathan sought to make good the damage; and it is in this context that the firm’s purchases of British stocks have to be seen. On [June] 20, the evening edition of the London Courier reported that Nathan had made “great purchases of stock.” A week later Roworth heard that Nathan had “done well by the early information which you had of the Victory gained at Waterloo” and asked to participate in any further purchased of government stock “if in your opinion you think any good can be done.” This would seem to confirm the view that Nathan did indeed buy consols on the strength of his prior knowledge of the battle’s outcome. However, the gains made in this way cannot have been very great. As Victor Rothschild conclusively demonstrated, the recovery of consols from their nadir of 53 in fact predated Waterloo by over a week, and even if Nathan had made the maximum possible purchase of £20,000 on June 20, when consols stood at 56.5 and sold a week later when they stood at 60.6, his profits would barely have exceeded £7,000.

(As a matter of fact, even the supposed quote from the Courier simply does not exist—and mention of it first appeared two years after the publication of the abovementioned anti-Semitic pamphlet, as a new footnote in the second edition of a very popular history of Europe.)

Ferguson goes on to demonstrate that the Rothschild brothers were in dire financial straits all through 1815 and beyond—they did come out on top in the end, of course, but not with a controlling interest in the Bank of England. (He also talks at length about their disorganized accounting practices. The whole chapter is incredibly detailed and fascinating—I haven’t read the whole book yet but I want to.)

Diane did a great Riskies post on this topic around the same time I made my original post, which includes a lovely account of the news of the battle reaching England. I really recommend watching the video even though it’s kind of long—and if you don’t want to watch the whole thing, at LEAST watch the first couple minutes so you can see the clip from a Nazi propaganda film depicting an exaggerated version of the apocryphal Consols story.

What’s your favorite/least favorite apocryphal historical anecdote?

(And by the way, A Lily Among Thorns fans, I am taking reader prompts and requests for mini-stories about the characters of Lily in honor of the Bicentennial, so stop by and tell me who/what you’d like to know more about!)