Recently, I played the character of Celia in a production of Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Celia and her cousin Rosalind are both daughters of dukes who, at the beginning of the play, live in luxury in a palace….until Rosalind is banished.  Then Celia and Rosalind run away to the Forest of Arden — Celia disguised as a shepherdess, and Rosalind disguised as Celia’s little brother. Due to Celia’s smart thinking, they’ve brought their “jewels and their wealth” along with them, so they take care of sheep the same way Marie Antoinette did, and have a lot of fun along the way.

Then Celia and Rosalind run away to the Forest of Arden — Celia disguised as a shepherdess, and Rosalind disguised as Celia’s little brother. Due to Celia’s smart thinking, they’ve brought their “jewels and their wealth” along with them, so they take care of sheep the same way Marie Antoinette did, and have a lot of fun along the way.

So, you’re thinking, what does this have to do with writing Regency romances? I’ll get to that in a moment. 🙂

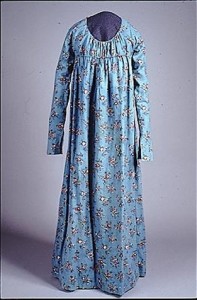

I wore two costumes in this play. In the first picture here (photo credit: Jesse Sheldon), you see me in a very tight, binding, ouch-my-back-and-shoulders-hurt pale blue gown with a train, a gauze overskirt, trailing sleeves that almost reach the ground, (fake) fur trim, and (fake) pearls sewn all over the gown. I also have a heavy necklace, and a headpiece with a back veil that’s so long it almost touches the floor.

In the second picture here (photo credit: Jesse Sheldon), I am royalty pretending to be common. My green dress still has some trim, but it’s much simpler, and much more comfortable. I skip, I run, I lie down under a tree at one point. I can do pretty much anything but bend forward too far (this dress has a pretty low neckline). 🙂

What I found right away was that the first dress very much changed the way I moved. It kept me upright. It kept me from walking backwards (unless I carefully handled my train while doing so.) It very much restricted how I could move my arms (which I could hardly raise). And sitting on anything was problematic — the “pearls” which adorned the dress are everywhere, so sitting involved sitting on a lot of large beads — rather uncomfortable!

Once I got used to the restricted movement of this gown, I learned its advantages. The long trailing sleeves made smooth, graceful arm movements very dramatic, and highlighted any hand gestures beautifully. The train, sleeves, and long veil clearly stated that this was an important person — and a wealthy one. It was true conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure in one costume.

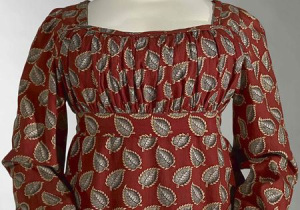

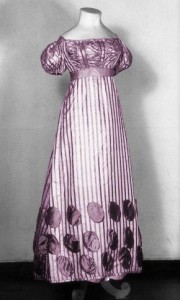

This leads me to think about the aristocratic ladies of the Regency period. I think one’s first impulse is to assume that all of those empire gowns were just so comfortable. But if you think about it, some of them were fussy…some had trains….some had huge headpieces with feathers…some were probably quite tight…and the stays certainly would have kept things like bending at the waist, and certain sorts of twisting, to a minimum…

So our heroines, particularly when dressed up for balls and such, probably moved and stood in a very different way from women who were servants or shopkeepers. Our elegant heroines would know that a small hand gesture or a graceful inclination of the head would speak volumes. Our young, tomboyish heroines might chafe against such restrictive clothing, and keep trying to do things they really shouldn’t (and getting in trouble.)

I’m sure none of this is new to most of you — but it’s the sort of thing that wearing a costume can make one ponder yet again! So what do you think the advantages and disadvantages of Regency costume were? What character or plot elements might a heroine’s costume cause, or reveal? Can you think of any dress-related plot points in Regencies that you’ve read?

All comments welcome!

Cara

Cara King, www.caraking.com

MY LADY GAMESTER — out now!