At the end of Part 2 in this series, we left our Regency heroine in her family’s still-room surrounded by the materials she has gathered for making a new supply of perfume. What has she harvested? Not apple blossoms, for gathering those would destroy the fruit crop. But perhaps roses? Violets? Lavender? Other herbs from the herb garden? Natural scent sources include flowers, buds, leaves, fruits, rinds, roots, wood, resins and bark of plants and trees, as well as animals.

Her choices are limited, in part because of England’s climate. If she lived in the south of France, near Grasse or Nice, she would be in the heart of some of the world’s best “perfume lands” and could have her pick of richly aromatic flowers and fruits, including orange blossom and jasmine. But even then, there are flowers she cannot use. In the Regency, there were not yet any “synthetic” scents that could substitute for an elusive natural fragrance, and there are a number of those—scents that defy extraction by any known method. (The reason can be a low concentration of fragrance in the material, but most often, it’s because the extraction process itself alters or destroys the scent.)

Lily-of-the Valley is one such flower. Its scent is very popular today and was even in earlier times. So how did Floris sell a scent under this name starting in 1765? They created a unique blend of other fragrances to approximate the desired scent. Floris’s formula for its famous Lily-of-the-Valley perfume was a highly guarded secret. The perfume was later taken off the market (I have not discovered when, but think it was pre-Regency), but it was re-launched in 1847 and has been sold ever since. The timing makes me suspect they took advantage of the development of chemical synthetics which began in the late 1830’s).

Other flowers that defy scent extraction include honeysuckle, pinks/carnation, sweet pea, lily, magnolia, lilac, mignonette, wallflower, sweet hawthorn, wood violet, muguet and gardenia. Modern chemistry has developed substitutes. Many people who are sensitive or allergic to “perfumes” are actually reacting to the chemicals in modern synthetic scents, so these are good ones to steer clear of in that case!

Whatever our heroine has chosen, she’ll need a significant quantity. (Wild strawberry might be great, but where will she harvest enough of it?) To capture the fragrance of the materials, she’ll need to make essential oils, but she might also have a home-made supply already stored on hand or have purchased some if she requires an imported scent. (Such oils could also be used to flavor foodstuffs, especially confectionery.) Most interesting perfumes are a mix of more than one scent, so having a good “nose” for creating pleasing combinations (or good recipes to follow) is helpful along with the store of oils.

She will also need a quantity of alcohol, and one of the many things she’ll need to know, or need to have noted in the recipe she consults, is whether that alcohol should be distilled from wine, vegetable or grain sources. Some essential oils only work well with a particular one. Purified alcohol that won’t add any fragrance to the mix is ideal. It may be used both for the extraction and for creating the oils –some oils, including rose, orange, and jasmine can be considered unpleasant in concentrated forms, causing headaches and other symptoms until diluted.

In Part 2 we mentioned the four methods of extraction that were in use during our period. Great advances in the techniques were developed later in the 19th century, which helped to lower the cost of commercial perfumes, as did the introduction of synthetic scents. But our heroine would choose whichever method she knows will fit the material she’s chosen.

For instance, lavender or peppermint (which both grow well in England) and rose leaves are sturdy enough to be distilled. This process using heated liquid and condensation can be dated as far back as 1200 BCE in Mesopatamia (where, incidentally, it was being used for perfumery). Our heroine’s still might be as small as this pottery still seen at Ham House (courtesy Deana Sidney via Sharon Lathan),

but given the amount of liquid in some recipes (for instance, one for rose water calls for 4lbs of rose leaves and 20 pints of water), much larger ones must also have been in use. The Ham House inventories from the 17th century list “pewter stills with glass heads” and also note chafing dishes and Bain Maries for heating the stills. I wish we could see those!

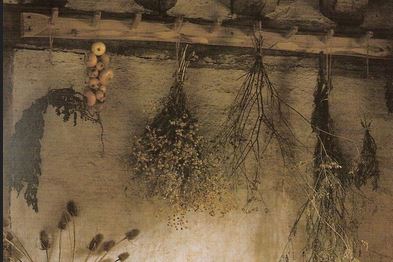

The other methods are also ancient –getting into all of them technically is another whole side-tunnel. (See how many rabbit tunnels this topic has?) But many flowers are too delicate to undergo distillation, even when kept above the water by a sieve—either the heat or the liquid/steam destroys them. Their essential oils are extracted using either maceration (rose petals, violets, etc), which involves repeatedly mixing the flowers into grease such as lard or an oil such as distilled bitter almond, or absorption (the most delicate, such as jasmine), where the flowers are spread on grease coated-plates or cloths soaked in oil. In both cases, the fragrance transfers into the grease (pomade) or oil and can be further processed with alcohol from there. Citrus fruits, such as lemons or oranges, best yield their fragrant oils by expression (also called cold-pressing) –the grating of the rinds and applying pressure to break down the material.

Once our heroine has invested the time and effort to have a store of essential oils, she is ready to mix her scents. Whether she decides to make “eau de parfum” or “eau de toilet” is a matter of how diluted with alcohol or scented water her finished product will be –the process to make them is the same until that step. She might have smelled a lovely perfume on someone she’d like to try to copy (perhaps at Almack’s in London she caught a whiff of Princess Esterhazy’s scent?), or she may have a recipe on hand. Depending on the quantity she is prepared to bottle and store, she might have to adapt the quantities to what she can manage.

This recipe is one for “approximating” the oldest perfume still being used today, Eau de Cologne, which lent its name to the more generic term “cologne” as a particular strength of perfumes and to “cologne alcohol,” a term used for the alcohol distilled from wine. Based on an Italian formula from the 17th century, Eau de Cologne was first made commercially as a wash and body rub in Cologne, Germany in the early-to-mid 1700’s and became popular after the French court adopted it. Like the French kings, even Napoleon is said to have bathed in it. The original recipe is still secret, but these are agreed upon as basic ingredients:

| Oil of bergamot | 2½ oz. |

| Oil of lemon (hand-pressed) | 6 oz. |

| Oil of neroli pétale | 3½ oz. |

| Oil of neroli bigarade | 1¼ oz. |

| Oil of rosemary | 2½ oz. |

| Alcohol | 30 qts. |

The bergamot and lemon oils are dissolved in the alcohol and distilled, and the rosemary and two types of blood orange are added afterwards. Also key is that only alcohol distilled from wine will give the desired results.

Have you ever used Eau de Cologne? (I remember being given tiny bottles of it as a child.) Do you have a favorite scent you enjoy? Or do you use essential oils for aromatherapy? Or are you allergic, or have you given up using scents in view of the many events that now prohibit them? Please leave me a note in the comments!

Coming in Part 4 (May 24): The Art of Perfumery, Scents for the Sexes, and the Truth about Bay Rum!