Here at the Riskies we return quite frequently to the topic of London’s Foundling Hospital, founded by sea captain Thomas Coram, composer George Handel, and artist William Hogarth. Today I’m sharing some recent finds I made–one is this quite splendid documentary Messiah at the Foundling Hospital (sit tight, it’s an hour long).

Here at the Riskies we return quite frequently to the topic of London’s Foundling Hospital, founded by sea captain Thomas Coram, composer George Handel, and artist William Hogarth. Today I’m sharing some recent finds I made–one is this quite splendid documentary Messiah at the Foundling Hospital (sit tight, it’s an hour long).

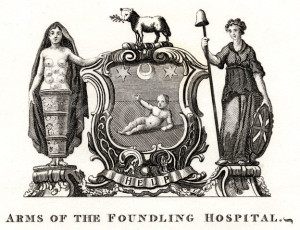

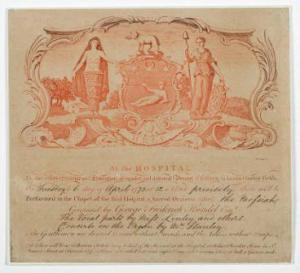

I discovered more about Hogarth’s contributions. He designed the logo in the form of a coat of arms, which is, as the documentary’s narrator points out, quite brilliant. Because it’s a coat of arms, it would have had instant appeal for the well-heeled aristocrats who were being targeted as donors. But the legend is in English–just one word: Help.

To be honest I’m not sure who the figure on the left is–a sort of female corkscrew? Anyone know? On the right is Britannia. The rest is self-explanatory, the baby and the innocent lamb. Anyway, the point is that this worked. It became hip and fashionable to be a philanthropist.

Hogarth also designed the children’s uniforms, some of which are on display at The Foundling Museum in London. (Ignore the well-scrubbed angelic appearance of the children in this painting. The clothes are correct.)

Hogarth also designed the children’s uniforms, some of which are on display at The Foundling Museum in London. (Ignore the well-scrubbed angelic appearance of the children in this painting. The clothes are correct.)

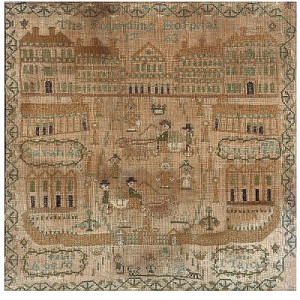

One perspective I’ve never encountered before is what other, more fortunate, children thought of foundlings and orphans. Some families might have a young maid who was trained at the Foundling Hospital.  One can only hope that no impressionable child saw the dying and abandoned babies on the streets of London whose fate so moved Coram. Here’s a sampler made in 1825 by ten-year-old Mary Ann Quatermain.

One can only hope that no impressionable child saw the dying and abandoned babies on the streets of London whose fate so moved Coram. Here’s a sampler made in 1825 by ten-year-old Mary Ann Quatermain.

But back to those uniforms. What happened to the clothes the children wore when they were admitted? Historian Alice Dolan tells us that:

In 1757, when the Hospital was overwhelmed by the clothing due to the large influx of children, the Hospital committee decided to sell the

‘old Raggs and useless things brought in with the Children of this Hospital’

because they were causing problems with ‘Vermin’.

After enquiries, the Hospital Committee decided to sell to the rag merchant Mrs Jones in Broad St Giles who would pay 28 shillings a stone for linen rags and 4 shillings 6 pence a stone for woollen rags. This was more than twice what her competitor Joseph Thompson offered for the linen and woollen rags.

Considering the thousands of children were admitted to the Hospital, this was a valuable form of income. It’s a reminder too, that nothing was discarded–vermin or not–if it could be sold or upcycled.

The exhibit Threads of Feeling, some of the fabric samples and tokens mothers handed in with their babies for later identification, showed a few years ago at the DeWitt Museum in Williamsburg. Both I and Diane, who blogged about it, visited. While I was poking around online I checked out future exhibits at the Foundling Museum, although I doubt I’ll get to any. Are you planning, or have you been to, anything inspiring at a museum recently?