I’m not religious and I don’t do much over Christmas, but one thing I’ve done for years is to attend a performance of the Messiah. I’ve attended performances in concert halls with huge choruses and orchestras; and a memorable performance in York Minster during the power cuts of the early 1970s when we all kept on our gloves and hats and one very short intermission at which we all dashed out to the nearest pub for warming drinks. Last  Saturday I heard Messiah at Washington National Cathedral, performed with a baroque orchestra and an “authentic” chorus of a children’s choir plus male voices. It was really spectacular and in a gorgeous setting.

Saturday I heard Messiah at Washington National Cathedral, performed with a baroque orchestra and an “authentic” chorus of a children’s choir plus male voices. It was really spectacular and in a gorgeous setting.

Handel, however, composed it for Easter, and it’s still performed then. It has never waned in popularity–Mozart, Carl Maria von Weber, and Mendelssohn introduced it in Europe and the rise of choral societies in the later nineteenth century ensured its popularity. The world record for an unbroken sequence of performances is held by the Royal Melbourne Philharmonic, which has performed it annually since 1853!

Handel composed the work in 1741 in a breathtaking 24 days, despite a difficult relationship with librettist Charles Jennens:

Messiah has disappointed me, being set in great haste, tho’ [Handel] said he would be a year about it, and make it the best of all his Compositions. I shall put no more Sacred Words into his hands, to be thus abus’d.

Six months later Jennens was still unimpressed:

‘Tis still in his power by retouching the weak parts to make it fit for publick performance; and I have said a great deal to him on the Subject; but he is so lazy and so obstinate, that I much doubt the Effect.

Messiah premiered in Dublin on April 13, 1742 as part of a series of charity concerts in Neal’s Music Hall in Fishamble Street near Dublin’s Temple Bar. Right up to the very date of the premiere the performance was plagued by technical difficulties, and the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Jonathan Swift (under whose aegis the premiere was to be held) postponed it. He demanded that the revenue from the concert be promised to local asylums for the mentally ill. The performance was sold out, with gentleman requested not to carry swords or ladies to wear hoops, to make more room in the hall. Handel led the performance from the harpsichord with his frequent collaborator Matthew Dubourg conducting the orchestra.

Messiah premiered in Dublin on April 13, 1742 as part of a series of charity concerts in Neal’s Music Hall in Fishamble Street near Dublin’s Temple Bar. Right up to the very date of the premiere the performance was plagued by technical difficulties, and the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Jonathan Swift (under whose aegis the premiere was to be held) postponed it. He demanded that the revenue from the concert be promised to local asylums for the mentally ill. The performance was sold out, with gentleman requested not to carry swords or ladies to wear hoops, to make more room in the hall. Handel led the performance from the harpsichord with his frequent collaborator Matthew Dubourg conducting the orchestra.

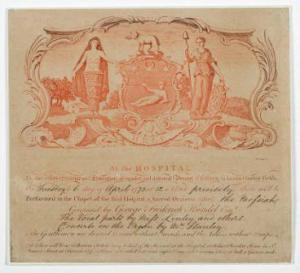

Handel continued to work on the score and excerpts were performed in 1749 to raise funds for the Foundling Hospital in London (of which Handel was a founder). In 1750, the final version was presented there and remained the fundraising vehicle for the institution.

Messiah is famous for the Hallelujah Chorus in which the audience stands, a tradition allegedly started at the first London performance on March 23, 1743. King George II rose, and so of course the rest of the audience had to follow. However, there are no eyewitness accounts, and the first mention of it comes 37 years later. Confusingly, it seems that audiences of the time liked to stand to certain pieces of music, such as the Dead March from Saul, and an audience member of a 1750 Messiah noted that the audience stood for the “grand choruses” (note the plural):

Audiences may have been spontaneously standing not because of royal example, but because of the confusing oddity of Handelian oratorio, and the additional oddity of Messiah itself. Handel’s hybrid of sacred subjects with operatic style, moving Bible stories into secular venues, had already struck some puritanical Britons as curious, or worse; Messiah went further, its libretto (by Charles Jennens) not even a dramatic narrative, but a theologically curated collection of Scripture passages.

“An Oratorio either is an Act of Religion, or it is not,’’ complained one anonymous critic on the eve of the London premiere of Messiah. “If it is one I ask if the Playhouse is a fit Temple to perform it, or a Company of Players fit Ministers of God’s Word.’’ The sermon-like atmosphere of Messiah may have triggered audiences’ churchgoing reflexes, and they may have felt compelled to respond, standing for choruses as if they were hymns – better to be piously safe than sorry. Read more

Tell us about your favorite Christmas music!