Saalburg: Porta Praetoria (the main gate)

As I have surely already mentioned in an earlier post, one of the settings of my upcoming Roman romance EAGLE’S HONOR: RAVISHED is based on a real fort at the Upper German-Raetian limes: the Saalburg, which today is a renowned open air museum with reconstructions of several of the Roman buildings and fortifications. As I was preparing the Author’s Note for my novel, it struck me how many lives this Roman fort has had – and not just in the Roman period.

The first fort on this site was built in timber, but was soon replaced by a larger fort built in timber and stone. A few years later, that fort was expanded and its defenses strengthened. Finally, at some point in the early 270s, the Romans gave up this stretch of the border and withdrew across the Rhine. The fort was abandoned and fell into ruins.

The Germanic people who moved into the area didn’t have much use for stone buildings, but from the Middle Ages onward, the stones from the fort were used for various building projects in the region. The original Roman name of the fort was forgotten; indeed, the very fact that this used to be a Roman fort was forgotten as well. The modern name, Saalburg, dates to the early 17th century and suggests people took the walls to be the remains of an early medieval castle.

It was only in 1723 when a stone altar bearing the name of Caracalla was found that people realized the Saalburg was actually a Roman ruin. But at that point only antiquarians (who were generally considered to be really strange people anyway) were interested in musty ruins, and so the Saalburg continued to be used as a most convenient stone quarry until 1818.

In the early 19th century archaelogy was still in its infancy, carried out by interested amateurs. In England William Cunnington, who started to do excavations of prehistoric sites in Wiltshire in about 1798, revolutionized the methods of archaeology, e.g., by carefully recording digs and finds. But it would take another few decades before archaeology became professionalised.

The increasing professionalisation of archaeology becomes also apparent when we look at the history of excavations of the Saalburg: from 1870 onward, the excavations were state-funded, and the men overseeing the digs aimed at using scientific methods and presenting their findings in a scientific way.

And when plans were made to not just excavate the remains of the fort, but also to reconstruct key buildings such as the principia (the headquarters building), the latest archaeological and historical findings were employed to make the reconstruction as faithful to reality as possible. This first phase of reconstruction work lasted ten years, from 1897 to 1907, and received support from Kaiser Wilhelm II himself.

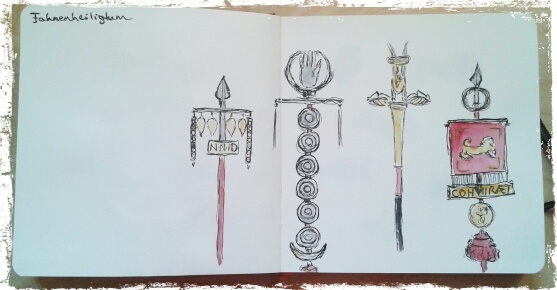

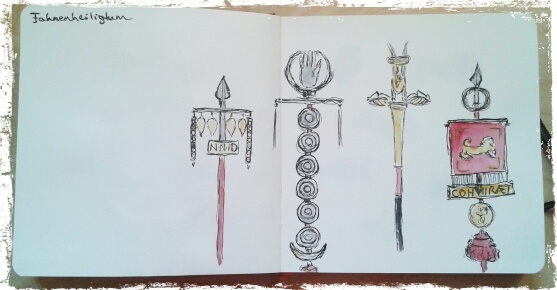

The military standards at the Saalburg

While this support was no doubt beneficial, it also meant that the Kaiser took an active interest in the project and in some cases influenced the way the reconstruction was done. The most obvious example of this is the presence of an eagle standard in the shrine of the standards in the principia. In Roman times, only legions fought under the eagle standard, and the Saalburg never housed a legion, but only ever auxiliary troops. However, due to the imperial symbolism of the eagle, the Kaiser insisted that the eagle standard was included.

Moreover, in the years since 1900, new research into Roman military architecture has revealed that parts of the early reconstruction are incorrect, for example, the walls surrounding the fort would have been white-washed and the towers of the main gate wokuld have had been higher. Further reconstructions from the 2000s reflect these newer findings.

The Saalburg today thus presents itself as a fascinating hotchpotch of visions of what a Roman fort might have looked like, and it represents yet another phase of that old Roman fort that was first built in this place in the early 2nd century.

Would the soldiers who were stationed here during the reign of Emperor Hadrian recognize their old home in the Saalburg. Bits of it, perhaps. Though I’m not quite sure what they would make of the eagle standard in their shrine…